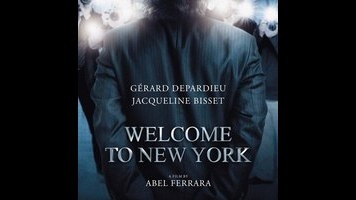

“No one wants to be saved. No one.” Abel Ferrara’s take on the Dominique Strauss-Kahn scandal, Welcome To New York, is a shadowland vision of hell as a place where everything is allowed—a compressed world of urges. Ferrara’s style is dark, vivid, and electric: inky interior spaces with small blotches of white and red light, silhouettes, jewels glistening in the blackness, figures slipping into frame and focus in a way that suggests that what the viewer is seeing is the unrehearsed rawness. A Strauss-Kahn stand-in named Devereaux (Gérard Depardieu) is rushed from hotel room to airport, from jail cell to rented townhouse and led down stretches of hallway and jetway folded like accordion bellows by long lenses and zooms. This is a film set entirely in places where people aren’t meant to stay for very long, a world of continual transit and gratification, with no endpoint. Maybe it’s the world that money creates for itself.

Ferrara (Bad Lieutenant, King Of New York) wildly blurs the line between star and role, opening with an out-of-character interview with Depardieu, and staging Devereaux’s arrest and booking with real cops and corrections officers. Stripped, self-destructive performances are the director’s stock-in-trade; his best work intersects the lurid with the tragic, finding that point where self-destruction and addiction erupt into emotional violence. Perhaps this is the native New Yorker and ex-junkie’s corrective to Shame; when Devereaux, arrested for sexually assaulting a hotel maid, tells his wife Simone (Jacqueline Bisset, exceptional) that he can’t help himself because he’s a “sexual addict,” it’s framed as an attempt to shift blame rather than a confession. The price of always getting away with it is the inability to understand what it is.

Welcome To New York paints Devereaux as an absurd and tragic figure, all appetite and impulse, who screws in 15-second bursts of thrusting, accompanied by dog-like yelps and whimpers, and framed with all the eroticism of an old man taking a dump. This is sex as pure compulsion, and it’s a credit to the integrity of Ferrara’s vision that this compulsion never comes across as sexy. What Ferrara, Depardieu, and co-writer Christ Zois have created is a character who can’t distinguish between sex and rape—a monster who knows he’s a monster, but not why.

“Stop doing that thing that men do, where they touch you and you smell them and then you’re imprisoned again,” says Simone toward the end of one of those intense domestic arguments that Ferrara directs better than anyone this side of John Cassavetes. As far as this couple from hell is concerned, the alternative to non-stop movement is legal or mental imprisonment, and the way to keep moving is to grease yourself up with money. And yet their world—claustrophobic, almost free of daylight, divided into rooms like cells—resembles nothing more than the police precincts and jails Ferrara navigates when Devereaux is booked and arrested. Different prisons, same crime.