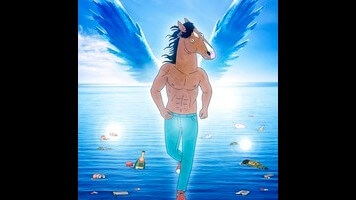

A silly satire of Hollywood culture and a dark character study about depression, BoJack Horseman’s best feature is that it doesn’t privilege one side of its premise over the other. It tells a grounded story about a washed-up ’90s sitcom actor struggling with alcoholism and self-loathing as he tries to make a comeback… only that actor is really an anthropomorphic horse, and he lives in an off-kilter version of Hollywood where humans and other anthropomorphic animals live side by side. It would be easy for creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg to lean on jokes about celebrities and the culture mill, which is what he did for most of the first half of BoJack Horseman’s first season, but he also dives deep into emotionally uncomfortable territory about self-destructive behavior, living with regret, and the viciousness of personal failure. It’s the equal partnership of intelligent, absurdist humor and biting drama that has elevated BoJack Horseman to one of the best shows on TV or the internet.

After the release of his tell-all memoir, BoJack Horseman (wonderfully voiced by Will Arnett) is enjoying some newfound notoriety while filming the lead role in the new Secretariat biopic. Still haunted by his past and struggling with depression, BoJack is trying to turn a new leaf with new girlfriend Wanda Pierce (Lisa Kudrow), a barn owl who has recently woken from a 30-year coma and has been named the head of programming at Major Broadcasting Network. Meanwhile, Diane Nguyen (Alison Brie), BoJack’s perceptive memoir ghostwriter, faces personal problems as the cracks in her marriage to Mr. Peanutbutter (Paul F. Tompkins) begin to appear. BoJack’s agent and ex-girlfriend, Princess Carolyn (Amy Sedaris), still searches for hot talent while also keeping BoJack in check, while BoJack’s lazy roommate, Todd (Aaron Paul), embarks on mini-adventures, like building a faulty rip-off Disneyland or trying to free a hormone-filled chicken from a terrible fate.

One of the best aspects of BoJack Horseman’s second season is its ability to leave its title character behind to explore other characters’ stories and the world Bob-Waksberg has created. One of the stealthiest elements of the series’ first season was its subtle world building: BoJack Horseman’s setting is completely absurd, but like the best off-the-wall creations, it also makes complete sense. It’s a world where A Ryan Seacrest Type and Some Lady (real character names) host Access Hollywoo (not a misspelling), J.D. Salinger works in a tandem bike shop, and Henry Winkler is best known for a guest role in Law & Order: SVU. But none of those details come across as forced—they feel like natural elements of a controlled, insane environment.

It’s this kind of irrational logic that drives much of the show’s comedy as well. Though BoJack Horseman is roundly praised for its drama, it has a divisive sense of humor that can either be too self-consciously clever or too knowingly stupid for some people. Admittedly, the series’ early episodes were comedically hit-or-miss, often relying heavily on cheap targets or leaning on smart-sounding monologues, but by the end of its first season, the series found its groove and could deftly move between different comedic modes. In its second season, BoJack Horseman takes its comedic sensibility to a whole new level by increasing the density of the jokes. There are so many animal puns, background visual gags, understated and exaggerated wordplay, and obvious but brilliantly executed laughs in the series that it rewards and often requires multiple viewings. Not since the early seasons of Arrested Development or the best years of 30 Rock has a series committed to the joke-a-second model like BoJack Horseman does.

BoJack Horseman is a Netflix original series, and because the streaming service encourages and incentivizes binge-watching, much of its original programming has embraced intense narrative serialization because there’s a better-than-likely chance their audience will be able to follow all the details. But serialization is a double-edged sword: While it can engender complex, compelling storytelling, it can also add a weightlessness to individual episodes, as writers often treat them like puzzle pieces for a larger narrative instead of their own separate stories. Though BoJack has many serialized elements, each of its episodes tells its own discrete tale and doesn’t rely on the events of past or future episodes. The series has episodes that can be described using the Friends template of “The One With/Where…” such as “The One Where BoJack Can’t Act” or “The One Where Diane And Mr. Peanutbutter Get Into A Fight.” It’s a series that could easily fit into a weekly schedule on a cable network, and while that may not seem like a huge selling point, it’s such a nice change of pace from other streaming content that has too quickly embraced the binge-viewing model of storytelling.

BoJack Horseman isn’t perfect. There’s still some roughness around the edges, and the series has a tendency to beat some jokes into the ground—like the substance-abuse problems of BoJack’s one-time co-star, Sarah-Lynn—but for the most part, it’s an entirely unique, funny, and melancholic exploration into the heart and mind of someone struggling to put his life back on track after a series of dark turns. It’s a series that excels at dispensing truthful, fatalistic wisdom like, “There’s no shame in dying for nothing. That’s why most people die,” or “I don’t care whether you’re happy. I care whether you do your job.” These sentiments are comforting rather than just cynical because the writing illustrates a deep well of empathy for all of its characters, even when they’re digging themselves into holes of incalculable depth. It skillfully shifts between comedy and drama because it doesn’t treat them like two different genres, such as a flashback to BoJack’s early childhood as he tries to listen to Secretariat’s answer to a BoJack-submitted question on The Dick Cavett Show over the sounds of his parents fighting. BoJack Horseman understands that life is tragic and comic in equal measure, and that embracing that idea without sacrificing one for the other is the key to success.

Reviews by Caroline Framke will run daily through July 28