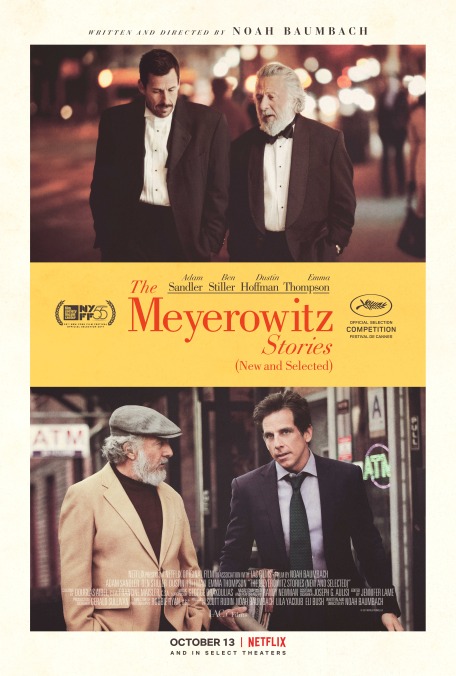

Adam Sandler and Ben Stiller express brotherly love in Noah Baumbach’s moving Meyerowitz Stories

Harold Meyerowitz, the unsung artist and shitty father Dustin Hoffman plays in The Meyerowitz Stories (New And Selected), is a fresh addition to Noah Baumbach’s ever-expanding gallery of neurotic, narcissistic New Yorkers. One could be forgiven, however, for confusing him for the older, squatter version of a different character: Bernard Berkman, Jeff Daniels’ breathlessly pompous professor from The Squid And The Whale, who Baumbach not so loosely (or secretly) modeled on his own father. Harold, like Bernard, is an arrogant academic, bitter about a creative career that never quite exploded. They even talk the same, these two bad dads: When Harold describes one of his sculptures as “a minor work,” fans will be reminded of how often Bernard used the same pretentious turn of phrase. Was it thrown around freely in the Baumbach house?

Divided into chapters that shift the focus among members of the title clan, The Meyerowitz Stories is about what’s it like to be raised by a limited, limiting man like Harold (or Bernard, or maybe their joint inspiration)—to grow up in his shadow, to resist his influence and practically beg for his love. But it wouldn’t really be accurate to describe this funny, bittersweet comedy as any kind of Squid And The Whale sequel, spiritual or otherwise. For one, Baumbach is working in a less explicitly autobiographical vein. The real difference, though, lies in tone and attitude: If he’s made another (more heavily) fictionalized family portrait, it’s one colored by a heartfelt generosity, a warmth even, that’s a far cry from the venomous insight that was the filmmaker’s stock in trade a dozen years ago.

The first Meyerowitz we meet is eldest child Danny (Adam Sandler), a lapsed musical prodigy, unemployed, nearly divorced, nursing a nagging limp. He’s come to New York to see his bright teenage daughter, Eliza (Grace Van Patten), off to film school, and also maybe to spend some time with his dad and his sister, Jean (Elizabeth Marvel). Danny reveres his father’s work, which has largely been ignored by the art world over his half-century career. But respect isn’t a two-way street in the Meyerowitz family—perhaps as a reflection of his own failures, Harold treats his first two kids, whom he had with his first wife, like disappointments.

Dad’s pride is reserved almost exclusively for his youngest: Danny and Jean’s half-brother, Matthew (Ben Stiller), the golden child of the family. An accountant who lives in Los Angeles, where he balances the books for rock stars, Matthew has his own wife and child to whom he struggles to connect; he’s also got his own issues with Harold, whose admiration for his professional success—his ability to actually make money—has an undercurrent of resentment. Meanwhile, no one gets along perfectly with Harold’s third wife, Maureen, a loopy lush played by Emma Thompson.

Borderline theatrical in structure, The Meyerowitz Stories gradually draws this fractured Jewish family back together through circumstance: a contentious plan to sell the family home, a retrospective of Harold’s work arranged by Danny and Jean, a medical emergency. Baumbach, who’s honed his comic dialogue to a furious bebop point in recent films like Frances Ha and While We’re Young, keenly understands how these estranged relatives would speak to and around each other, peppering in cultural name-drops (Warhol, Neruda, Kubrick) and insecurities alike. There’s a vast shared history in his pages of prickly dialogue, enhanced by the peerless ensemble he’s hired to deliver it, from Hoffman—face submerged in snow-white hair, nailing the distracted irritation of a slowly fading parent—to Marvel, who lends Jean a droll, wallflower wit, not far from a grown-up, live-action Daria.

But as an acting showcase, the film belongs chiefly to its moonlighting funnymen. By now, it’s not surprising to see Stiller play up the serio end of seriocomic for Baumbach, who coaxed a richly dramatic performance out of him in Greenberg. But as Matthew, the more ostensibly put-together of the Meyerowitz boys, he has a scene of such tender vulnerability that it makes you wonder if you’ve ever really seen the terrific actor he keeps hidden behind the various Zoolanders on his résumé. Sandler, meanwhile, hits new notes of underachiever pathos. As with his two most celebrated departures, Punch Drunk Love and Funny People, there’s a meta dimension to the part, which finds him playing a gifted artist who’s squandered his talent. (Sound familiar?) But Baumbach doesn’t so much subvert the actor’s common tricks—temper tantrums, silly ditties, and a general hangdog quality are all accounted for—as chisel an affecting character out of them. He has not been cast against type.

The Meyerowitz Stories isn’t the funniest or sharpest of Baumbach’s comedies—it lacks the zing of his work with Greta Gerwig—but it may be the most scene-for-scene moving. For every moment that bluntly reveals the distance between these characters, there’s one that implies bonds too strong to be broken: Danny sitting at a piano with his daughter, knocking out a gentle duet they wrote together; a heart-to-heart that comes to blows, under the influence of competing drugs; a series of painfully public addresses that demonstrate how, strangely enough, mutual animosity toward a parent can bring siblings closer together. And Baumbach has a few fresh comic devices up his sleeve, like the hilariously neutering way he’ll cut off a bellowing outburst mid-scream.

There was a time when Baumbach could take his talent for character dissection almost too far; Greenberg and Margot At The Wedding pushed his uncharitable side to its acceptable limit. That the writer-director has found a way to preserve his acerbic wit while also deepening his humane appreciation for life’s screwups adds evidence to the case that he’s one of the most consistent (and consistently rewarding) American filmmakers working today. This is not, in Harold or Bernard’s words, a minor work. Few of Baumbach’s movies are, really.