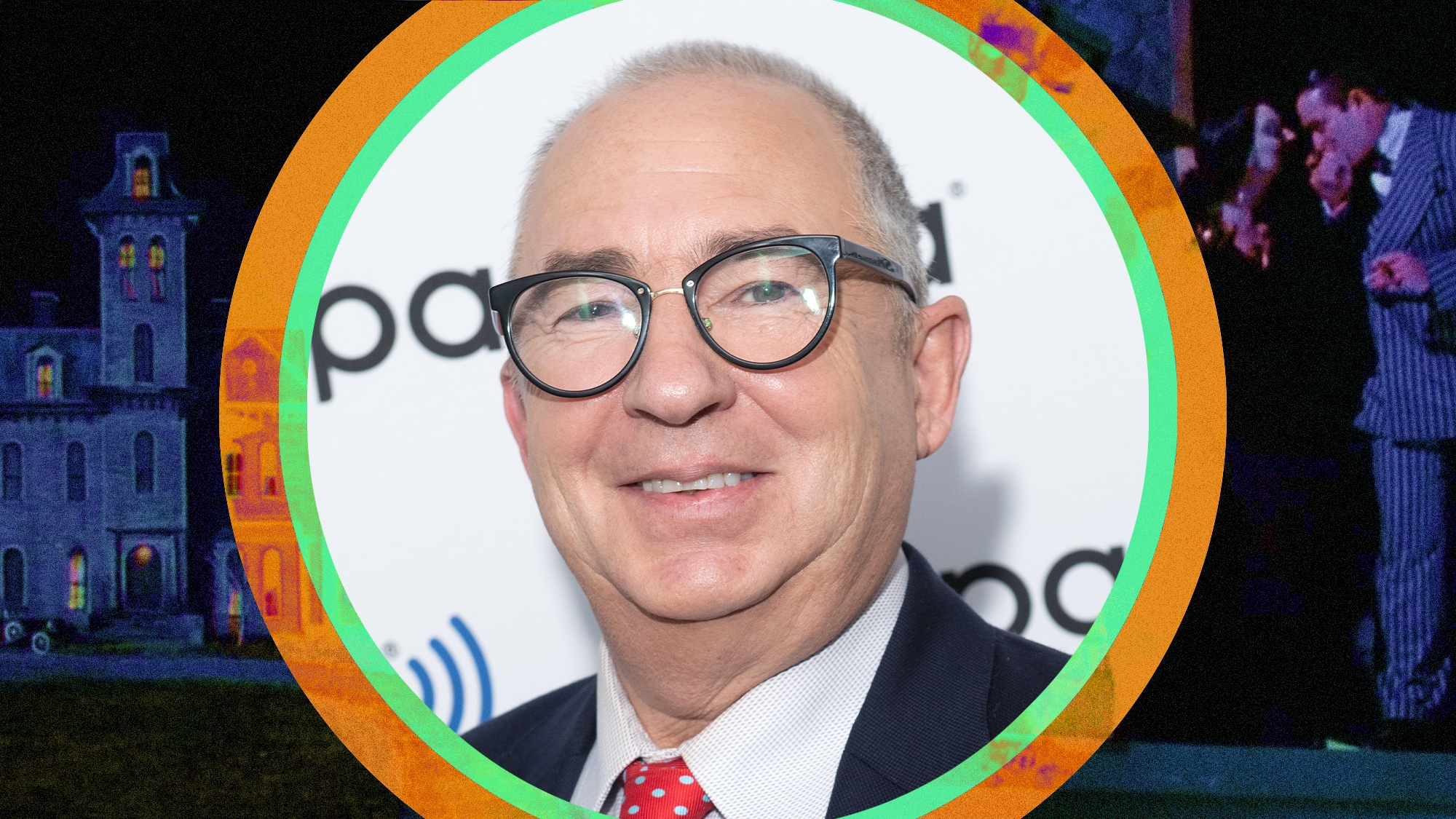

Director Barry Sonnenfeld says his Addams Family movie would cost 5 times as much, be half as good if it were made today

The legendary director recalls the “romantic” heart behind his ooky classic

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Barry Sonnenfeld knows the internet adores Addams Family Values, but the director’s always going to have a soft spot for his original, The Addams Family, which celebrates its all-together ooky 30th anniversary this fall.

“People always say, ‘Oh, I prefer the second one,’ and I always say that, sure, Addams Family Values is funnier, but The Addams Family is more romantic,” Sonnenfeld tells The A.V. Club.

Beneath the cobwebs, this playfully macabre comedy holds up three decades later precisely because it is such a big-hearted family love story. It’s there in the way Gomez (Raúl Juliá) and Morticia (Anjelica Huston) look at one another, the way Wednesday (Christina Ricci) and Pugsley (Jimmy Workman) put a gleefully arch spin on sibling rivalry, and the way Thing’s always there to lend a helping hand. The Addamses may be grim, but they have each other’s backs, ’til death do they part—and then some.

For Sonnenfeld, the soul of The Addams Family can be found in cartoonist Charles Addams’ drawings for The New Yorker, which the director grew up admiring. While he acknowledges the importance of ABC’s The Addams Family series (1964-1966) in bringing the characters to life—and giving them their names—he was intent on making his 1991 revival a proper tribute to the spirit of Addams’ work.

In honor of the film’s thirtieth anniversary, Paramount is releasing an extended 4K cut, which gave The A.V. Club the opportunity to ask Sonnenfeld to reflect on his directorial debut. Having previously worked as the cinematographer on classics including When Harry Met Sally, Big, and Raising Arizona, the director shares filmmaking do’s and don’t’s he learned from his previous collaborators. Sonnenfeld also touches on stepping out of the shadow of Tim Burton, making Thing believable in a pre-CGI world, and reveals how Christina Ricci convinced him to change The Addams Family’s final scene.

The A.V. Club: The Addams Family was your debut feature as a director, but you’d previously been the cinematographer for filmmakers like Rob Reiner, Penny Marshall, and the Coen Brothers. How did working alongside those directors help prepare you for this film?

Barry Sonnenfeld: I didn’t know I was going to be directing this until I was two weeks from finishing Misery—that’s when I was sent the script. I watched other directors direct actors, so I knew what was more effective and what was less effective. I made certain observations. I didn’t think, “When I direct, I’ll never do this.” But, when I became a director, I remembered all the things I didn’t want to do.

To give you an example: I think it’s really important that directors direct from the camera. Most directors now direct from video village. You know, they set up chairs over there, they put a big monitor there, the director’s there, the producers are there, the [director of photography] ends up there, and the script coordinator—and what happens is, you become lazy. You start yelling, “Do one more!” Well, why? Why are you doing one more? No director should ever say, “Do one more.” You’ve got to say, “Do it faster, angrier, sadder.” You got that one, why are you doing one more? Give them some advice.

I watched Penny Marshall on Big, who would always direct from the monitor and yell, “One more!” And then I’d go over to Tom Hanks, and Hanks would say, “Can you ask Penny what you want differently?” And I go, “Hey, yeah, hold on Tom.” So I go back to video village: “Hey Penn, Tom wants to know what you want him to do differently.” And she would say [in a thick New York accent], “Tell him one more.” So I’d go back to Tom and say she just wants one more, and it never bothered him. [Laughs.]

But I decided I’ve got to direct by the camera so that the actors know that there’s an audience right there. And then you can call cut and immediately say, “Yes, great, but do this and over here.” But I was scared, man, I was scared of actors. I didn’t know if I would know how to talk to them. But all I’d ever say is “faster” or “flatter,” and they’d go faster or flatter. And it works! That’s all I said to Lee Pace while shooting the Pushing Daisies pilot for 19 days: “Lee, faster!” And if you watch the pilot again, Lee is racing through that. [Laughs.]

AVC: Well, timing is everything—especially when it comes to a comedy like The Addams Family, which is so densely packed with zippy dialogue and visual gags.

BS: Yeah, and the inspiration was always in Charles Addams’ drawings. And there are actual images that I just stole outright from his work and turned into two-dimensional moving pictures. Like, there is a Charles Addams drawing of someone playing with an HO Gauge train set, and it shows a commuter looking out the window and seeing some man playing with the controls of his train set. And I stole that and used it exactly. In fact, I’m the guy in the train!

That is an exact example of paying homage to Charles Addams. And the opening shot of the Addams family pouring oil from a cauldron onto the carolers is also a drawing that Charles Addams had done. So I took great inspiration from those images; I grew up with them! I read The New Yorker every week—or, rather, my dad did, and I would look for the Charles Addams drawings.

AVC: Reportedly the film was originally offered to Tim Burton, who, it turns out, is now working on a Wednesday Addams-focused series for Netflix. Coming on to this film, was there a sense that you wanted to leave a distinctive mark of your own and avoid comparisons to Burton?

BS: I said, “Why me?”, and they said, “Because we went to Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam and, after all the good directors passed, we thought we’d go to you!”, which is very funny. They wanted a visual stylist, which both Tim and Terry are. I’m the most emotional director of the three, you know? I think those guys are great directors, but what I bring to it is slightly more emotion. Which is why I think that Raul and Anjelica’s performances are so good, because I lean in towards emotional stuff.

I didn’t think I needed to leave my own mark, per se, as opposed to Tim or Terry. But what I brought to it was two things. One is that I truly was an expert on Charles Addams’ drawings, and I wanted to get as many of those drawings into our film as possible. I wanted to pay homage to those drawings.

And, also, I’ve always believed as a cameraman—and now as a director—that the camera is a storytelling device. It’s more than just a recording device. So, whether it’s Raising Arizona, or Three O’Clock High, or Throw Momma From The Train, I’m always using the camera to help tell the story: pushing in, pulling back, wide-angle lenses, center punch. So, that’s the other thing I brought: A very specific visual style. I have a very specific, wide-angle-lens aesthetic, and The Addams Family had that aesthetic. We used massive sets, not a lot of close-ups—and often, if there were, they were emotional moments between Raul and Anjelica—but not a lot of close-ups.

AVC: You weren’t the biggest fan of the initial The Addams Family script, so knowing you have such a familiarity with Charles Addams’ work, what was missing? How were you able to help bring the spirit of Addams back to The Addams Family?

BS: What was missing was Charles. What was missing were those drawings. It didn’t have the quirky darkness of his drawings, but instead had this silly, white-bread [humor] of the television show. The [first] script was much more like the show—it was set-ups and punchlines and jokes, and there was no emotion. The original writers, I think, didn’t respect the love and joy that Gomez and Morticia have for each other, how Gomez and Morticia love their children unconditionally.

You know, people always say, ‘Oh, I prefer the second one,’ and I always say that, sure, Addams Family Values is funnier, but The Addams Family is more romantic. I just love the romance between Gomez and Morticia, and how Raul Julia and Anjelica Huston play them.

And the other thing that happened after our first table read was that the cast rebelled. They finished reading and they discovered that Fester is still an imposter—not the real Uncle Fester. They went crazy, and they got Christina Ricci as their spokesperson—which, you’ll never win that debate. And we didn’t! We realized they were right. In our original ending, we had Fester remaining an impostor with Gomez inviting him in anyway, which worked as an intellectual ending, but not an emotional ending.

AVC: So what did Christina Ricci end up saying? How did she make the case for the real Uncle Fester?

BS: The actors all met, and then they came over to us. Anjelica started by saying, “We need Fester to be the real Fester, and Christina will explain the reasons why!” But before she did, I said, “Hey, wait, let’s ask Christopher Lloyd, who’s playing Fester. Do you care if you’re the real Fester or not?” And Chris said, “I don’t care!” [Laughs.]

But then Christina said, “Barry, let us explain to you the reasons. The audience will not be satisfied with that ending. If Gomez invites this impostor in and says, ‘You out Fester’d Fester,’ the audience won’t accept that! They’ll just want to know where the real Fester is. And how could Gomez no longer care about the brother he’s pined over for decades since he was lost in the Bermuda Triangle? Will Fester ever show up again?”

The bottom line of what Christine was saying was that we couldn’t let the audience leave the theater with these questions, that we want them to feel satisfied, emotionally. So I said, “Okay, okay, fine!” And then Paul [Rudnick] wrote a better ending. [Laughs.] We changed it because the cast rebelled and because Christina was so damn articulate.

AVC: Something that really stood out while revisiting the film was just how good it looks, even 30 years later. Are there any practical or visual effects you feel especially proud of to this day?

BS: Definitely Thing, you know, because we didn’t have a lot of money! Chris Hart, who is a magician, played Thing, and he would wear a black-sleeve shirt and then we created a prosthetic additional piece of arm that had a cup to it, so we could erase the arm, but the hand would still have an ending to it. Because we didn’t want veins or anything like that, right? What’s amazing is it’s pre-CGI.

I always say this about Blood Simple, which is the first movie I was on, and I’ll say it about The Addams Family: If we were doing either of those films today, we’d have somewhere between five and 10 times the budget on Blood Simple, and five times the budget on Addams Family—and they would have been half as good! Because we would have had CGI. And, because we had Chris Hart, I could direct the actual Thing in real time.

There’s a scene where Chris Hart is doing Morse code to Raul Julia as Gomez. At first, he’s using sign language, but he’s talking too fast, and Gomez tells him to slow down. So then Thing takes the spoon out of Gomez’s cereal and starts Morse-coding it. [And] it’s really hard to get CGI animators to do comedy. They can do explosions, they can do train wrecks, they can do other worlds, but a lot of them don’t have comic timing. That’s why you want actors.

Same thing with Men In Black. Rick Baker, thank god, taught me that in pre-production. He said, “You don’t want those worm guys to be CGI. We’re going to use rod puppets, you can direct them, and Tommy [Lee Jones] can act to them.” As opposed to just having a blank wall and doing that in post. And Rick said, “Plus puppeteers are SAG members, and they’re actually funny, so you can direct them.” So, on the set, I remember Tommy comes into the coffee room and, in that moment, I said, “Tommy, ask what kind of coffee they’re drinking!” And then I told the worm-guy Sleeble to say Viennese cinnamon. [Laughs.] We could just do it all right there.

So, the fact that Thing was a real actor—Chris Hart, great magician, great guy, very patient—is something I’m so proud of. And it’s something we wouldn’t do now. We would be doing all that in post and it wouldn’t be as good.

AVC: It makes a huge difference. There’s such a tactile quality to it. You don’t really have to suspend your disbelief that Thing is in the room with them because he really was.

BS: And you know what else I just realized? If we were also shooting it today, we’d be shooting it on video instead of 35mm film. There would be HDR [high dynamic range]—and no matter what anyone tells you, HDR is a villain. It’s not a good thing; it’s a marketing tool. 4K is a marketing tool. All these streaming studios say, “You’ve got to shoot in 4K, and you can’t use the Alexa because it’s only a 3.8K chip.” But actors don’t look good in 4K—you see every bit of makeup. So what do we do now? We shoot in 4K because it’s a marketing tool.

And, by way, you can release things [in 4K]. Like, I’m glad that we’re releasing this in 4K. But we didn’t shoot it on video in 4K. So, what we do now is, the DP either buys really crappy old lenses that aren’t sharp. Or, if we’re using sharp lenses, he puts so much diffusion in front of the lens—fog filters and glitter filters—so the actors look beautiful again. So, all we’re trying to do is do away with all the the shooting on 4K. Releasing on 4K is brilliant, but you don’t want to shoot it that way. You want to shoot on film. So Addams Family would not be nearly as beautiful if it was reshot today.

The newly restored cut of The Addams Family is available now on Digital 4K Ultra HD, and comes to Blu-ray on November 9, 2021.