Addiction is the real monster of Werewolf, a striking addition to the junkies-in-love genre

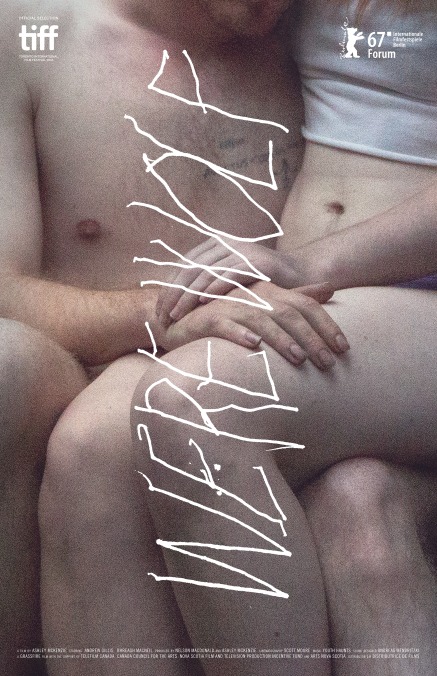

No startling physical transformations occur in Werewolf, the scrappy feature debut of Canadian director Ashley McKenzie. Instead, the film’s two main characters, Nessa (Bhreagh MacNeil) and Blaise (Andrew Gillis), are depicted from the outset as something less than human—not remotely in a judgmental way, but as a means of conveying how they’re perceived by others. McKenzie shoots both actors tightly, often showing only part of their faces, or cutting off their heads with the top of the frame; even when they’re just relaxing together, completely alone, the visual focus is apt to be on hands, feet, shoulders, thighs. It’s a risky strategy, especially for a movie with admirably little interest in exposition or backstory (not to mention a willingness to disappoint horror fans with its strictly metaphorical title). But this formal claustrophobia sets Werewolf apart from the surfeit of other no-budget indies about recovering drug addicts, which tend to follow such a similar trajectory that they can sometimes be difficult to tell apart.

Werewolf also excels in the specificity of its details. Nessa and Blaise, who live in what appears to be a fairly nondescript area of Nova Scotia, are on the methadone program, and the film impassively observes their daily ritual of hoofing it to the local clinic and answering a barrage of diagnostic questions in order to receive a dose. The rest of their day involves fruitlessly applying for low-income public housing (which prioritizes applicants with children) and trying to scrape up a few dollars for food by mowing people’s lawns. The latter requires them to lug their own beat-up lawnmower everywhere they go, at least until the motor breaks down and they’re a good $58 short of the $60 they need to fix it. Blaise has more or less accepted that this is his lot in life, while still being perpetually pissed off about it. Nessa, however, begins taking tentative steps toward rejoining society, even as it becomes apparent that doing so will probably require abandoning the stubbornly fatalistic man she loves.

Narratively speaking, there’s nothing groundbreaking here; events play out pretty much as you’d expect, especially if you’ve seen The Panic In Needle Park or Rush or Another Day In Paradise or Heaven Knows What or any of the zillion other junkies-in-love movies. (Nessa’s growing desire for a normal life, which alienates the only companion she’s known, also echoes Debra Granik’s forthcoming Leave No Trace, though that’s a coincidence and the films have little else in common.) All the same, Werewolf unmistakably announces McKenzie as a potentially significant new voice, gifted enough to make well-trod ground seem newly landscaped. She edited the film herself, creating a rhythm that’s slightly jumpy without crossing the line into jagged cold-turkey cliché, and gets effortlessly natural performances from her two leads, neither of whom has acted onscreen before (save for Gillis’ role in one of McKenzie’s earlier shorts). It’s strong enough work to suggest that she’s just a full moon away from metamorphosing into a major talent.