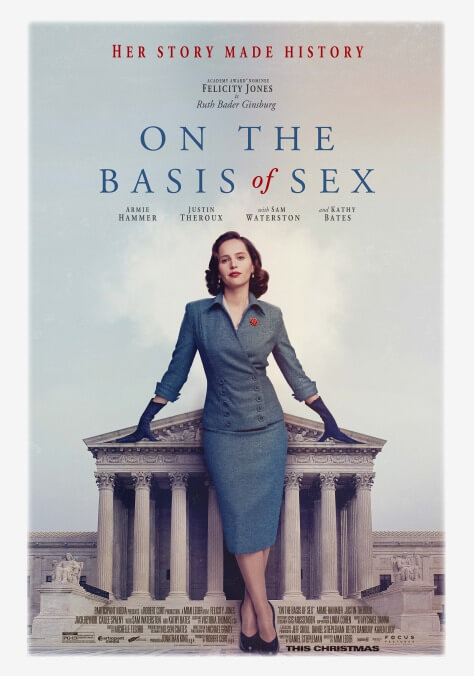

After a clumsy opening statement, RBG biopic On The Basis Of Sex effectively argues its case

Avoid the extended edition of this. Check out the director’s cut of that. Take a machete to the Star Wars universe. The history of movies is littered with recommendations on the best way to watch them. When it comes to the new biopic On The Basis Of Sex, improving the viewing experience could be simple: Just skip the first 30 minutes. The film’s opening act traces the fraught Harvard Law School experience of future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Felicity Jones, serviceable if not exactly thrilling). It’s an impressive journey unimpressively retold, relying on overly familiar biopic tropes about the difficulty of being a woman in the man’s world of the 1950s. It also primes the audience for a far more simplistic female-empowerment story than the one we actually get. On The Basis Of Sex is ultimately less about one woman blazing a trail for herself and more about the slow, pointed deconstruction of an entire sexist social order.

After its messy opening act, the film leaps ahead to 1970 and zeroes in on one particular case that would eventually help launch Ginsburg’s work as the co-founder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. An unmarried Denver man named Charles Moritz (Chris Mulkey) is unable to take advantage of a caretaker tax credit to help him hire a nurse for his ailing mother because the deduction is limited to women and widowers. It’s a sex-based discrimination case in which the victim is a man, not a woman. And it gives Ginsburg an unexpected opening to challenge the centuries of legal precedent that have established rigid gender roles as the natural order of the world, not a form of discrimination.

While the ’50s opening act offers the easy “look how far we’ve come!” satisfaction of retro sexism, the 1970s portion provides no such easy outs. One of the film’s strongest through-lines interrogates self-proclaimed male feminist allies. ACLU legal director Mel Wulf (Justin Theroux in full ’70s smarm) sees himself as an advocate of Ginsburg’s cause—and to a large extent, he is. Yet he can also be hugely condescending, and is disinterested in treating Ginsburg as an equal. There’s a limit to his allyship, one he never thinks to examine because he’s already cast himself as a hero on the right side of history. Similarly, the film zooms past the many law firm interviews in which Ginsburg was flatly rejected to focus on the one interviewer who seems to be genuinely sympathetic to her struggles… before noting that, of course, he can’t actually hire her because what would the wives of his employees say?

On The Basis Of Sex emphasizes the limits of faux allyship by pointedly demonstrating what a true male ally looks like in Ginsburg’s husband, Martin Ginsburg (a charming Armie Hammer). As was compellingly explored in this year’s Ginsburg documentary RBG, the dynamics of Ruth and Marty’s marriage of equals were unusual for the time period. Marty handles the domestic duties of the Ginsburg household, including the cooking and emotional caretaking of their two children. His natural nurturing instincts tie into the court case at the heart of the film, one in which Ruth has to convince a trio of skeptical appellate court judges that it’s possible that an adult man might actually want to lovingly take care of his sick mother, not just use her as an excuse to cheat the tax system. On The Basis Of Sex asserts that the battle to defeat sexism can’t just be about women entering the professional sphere. It has to be about men being empowered in the domestic one, too. That’s an issue that’s plenty relevant today.

Director Mimi Leder (returning to the big screen after three seasons of work on The Leftovers) and first-time screenwriter Daniel Stiepleman (Ginsburg’s real-life nephew) have crafted a film that occasionally veers toward hagiography, but stays just on the right side of that line. If there’s a value to the opening act, it’s that it drills home the sense of quiet bitterness and resentment that settles over Ginsburg once she realizes that despite all her early gumption, the best she’ll probably be able to do is teach the law, not practice it. There’s a prickliness to the older Ginsburg’s staunchly serious personality, which manifests in her at-times combative relationship with her teenage daughter Jane (Cailee Spaeny), who’s coming of age amidst the burgeoning radical feminist movement and can’t always understand her mother’s more measured approach. It’s a compelling, if too neatly resolved, look at cycles of feminism and the conflicts between them. (Unfortunately, frequent comparisons between gender-based discrimination and race-based discrimination aren’t as well-contextualized as they should be.)

On The Basis Of Sex builds to an effective courtroom climax that argues that slow-and-steady legal change is just as important as flashier social revolution, especially when the two work in tandem. The film never quite loses its glossy biopic sheen; be prepared for some groan-worthy jokes about the wackiness of a neighborhood being renamed “SoHo” and the impressive abilities of a newfangled machine called a computer. But though it goes down easy, On The Basis Of Sex is smarter and subtler than it looks—or, anyway, how its first act makes it look.