Booze, babes, and brotherhood: This is the image of Greek life that’s dominated movie screens in the four decades since Animal House basically invented the modern campus comedy. No wonder young men keep subjecting themselves to the rigors of rushing; to hear the movies tell it, good times are but a paddling away. But there’s a university football field separating these onscreen bacchanals from the harsh reality painted by every headline controversy. Without even touching upon sexual-assault charges or recent racism scandals, Goat reveals something uglier than the usual endless party. For once, the frat boys are depicted not as lovable dolts or harmless pranksters, but as sadistic bullies. Likewise, their excessive initiation rites are played not for lowbrow comedy, but for something closer to horror. This is basically the anti-Animal House.

The story is true, which lends it an extra-disturbing charge, though certain details of the 2004 memoir from which it’s adapted have been tweaked. Goat begins with suffocating suspense, as 19-year-old Brad (Ben Schnetzer) foolishly offers a ride to a couple of strangers and is savagely assaulted by the townie carjackers for his trouble. It’s clear that Brad, deeply traumatized by the incident, feels emasculated. (“Do you think I’m a pussy?” he drunkenly asks during a vulnerable moment.) It’s also clear that he’s more sensitive and less confident than the swaggering college alphas who have embraced his older brother, Brett (Nick Jonas—yes, that Nick Jonas). But after a summer of recovery, Brad heads off to school (fictional Brookman, filling in for the real Clemson) and pledges Brett’s house, possibly under the false, unconscious assumption that assimilating into this wolf pack will heal his battered ego.

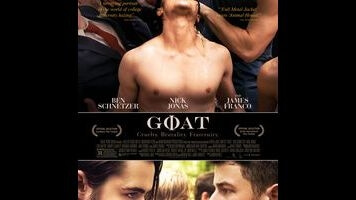

Directed by Andrew Neel (King Kelly) and co-written by wildly uneven Southern genre hopper David Gordon Green (All The Real Girls, Pineapple Express), Goat smartly acknowledges the allure—the immense social benefit—of the fraternity system. “I’m having sex for the first time in my life,” exclaims Brad’s roommate Will (Danny Flaherty), who’s even less of an obvious candidate for the brotherhood than Brad is, and an early blowout bash makes the frat lifestyle look as hedonistically fun as the college parties of any Animal House clone. Plus, there’s the whole all-for-one pledge, made by a legendary house alum (James Franco, kidding his own frat-comedy career in an inspired cameo) who drops by to extol the safety of numbers. For Brad, that may be the real appeal of Phi Sigma Mu: a support network during a difficult time, a group of new friends who have his back going forward.

It’s a lie, of course. The brothers’ vow of loyalty is a sucker bet, an excuse to indulge their worst impulses. With Hell Week, the pledges (or “goats”) find out what they’ll have to endure to make the cut. This is Goat’s raison d’être: a plunge into the queasy, dehumanizing spectacle of frat-house hazing. Neel gets his camera in close on these gauntlets of degradation—the drink-until-you-barf rituals, the verbal and physical abuse disguised as lighthearted torment, the hanging threat of sexual humiliation. (Let’s just say the title has a second meaning.) There’s a vindictive quality to it all, a sense that the actives are perpetuating a cycle of cruelty. And the military parallels are clear long before someone mentions Guantanamo Bay. As in the similarly grueling The Stanford Prison Experiment, the violence inflicted by supposedly upstanding college kids evokes a whole spectrum of nauseating human nature.

If there’s a bitter irony to these harrowing events, it’s that Brad ends up trading one form of brutalizing for another, punishing himself for his “weakness” by submitting to a sanctioned, socially accepted trial by fire. As a vision of toxic masculinity and the insecurities that inform it, Goat is shrewdly perceptive. As ripped-from-reality drama, it’s sensationalistic but a little anti-climactic—building and building in intensity, teetering into almost inevitable tragedy, and then landing on a final confrontation that’s just a touch unsatisfying, in the way real life so often is. Still, both Schnetzer and Jonas are quite good, locating an intimate, complicated tale of literal brotherhood within a larger study of the communal kind. And if Goat doesn’t achieve anything much deeper than a full-on immersion in the boot camp of fraternity culture, that’s plenty gripping on its own—not to mention plenty useful, at least for future pledges in need of a reality check after the warm, fuzzy distortions of, say, Neighbors.