“People never make films about ordinary people who don’t really do anything,” Naomi (Emily Browning) clumsily laments to her new employer in the opening minutes of Alex Ross Perry’s Golden Exits. As an Australian university student who’s come all the way to New York for a job, Naomi can probably be forgiven for not knowing that “ordinary people not really doing anything” describes a whole lot of films made in the city that never sleeps, including the one in which she’s unwittingly starring. But does Golden Exits really qualify as a vision of reality? Unfolding against an unglamorous backdrop of Brooklyn brownstones, nondescript diners, and cluttered basement offices, the film is superficially concerned with everyday disappointment and discontent, the dispiriting stuff of “normal” life. But Perry, the gifted indie darling whose last trip to NYC was the scathingly funny Listen Up Philip, has this time burrowed so deep into pastiche—into his obsession with recreating the feel of a certain kind of movie—that he’s made something ponderously artificial: a deadly fusion of the mundane and the affected, like some black-box-theater parody of an Ingmar Bergman art drama.

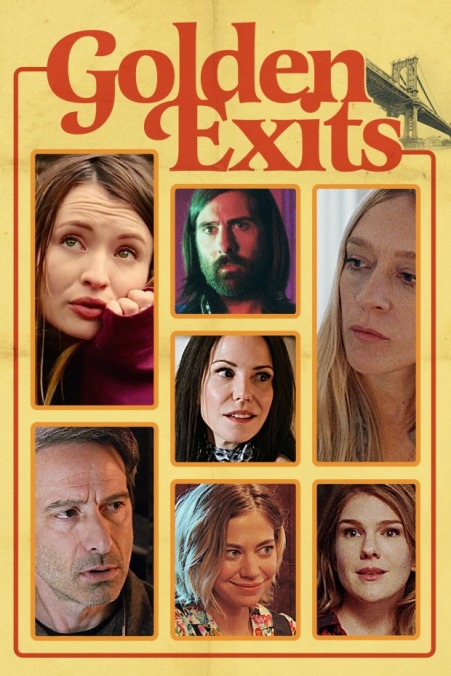

Naomi works for Nick, the milquetoast picture of male midlife crisis. In Perry’s shrewdest casting coup, Nick is played by one-time Beastie Boy Adam Horovitz, whose own iconically cool background only emphasizes how out-of-touch, how profoundly uncool, the character is. Nick hired Naomi to help with the organization of his dead father-in-law’s belongings, a job that his sister-in-law, embittered businesswoman Gwen (Mary-Louise Parker), wishes they entrusted to someone else. Meanwhile, there’s Nick’s wife, Alyssa (Chloë Sevigny), who may be the most distant and despondent psychiatrist in the tri-state area, judging from her habit of mournfully spacing out during sessions. Alyssa doesn’t trust her husband with a beautiful twentysomething assistant—and for good reason, as Nick has both a history of unfaithfulness and a crush on his new hire. (The latter is plain from the giant, telegraphing, close-up reaction shots of Horovitz’s slack-jawed leering.)

He’s not the only older, married man entertaining such thoughts: Recording-studio owner Buddy (a furry, stocky Jason Schwartzman) keeps stepping out on his wife and business partner, Jess (Analeigh Tipton), to flirt with Naomi, who he met 20 years earlier, when they both were kids. Neither of these men know each other, but their unhappy families, each unhappy in their own way, are connected through more than the looming threat of infidelity: Jess’ sister, Sam (Lily Rabe), also works as Gwen’s put-upon personal assistant, when not unloading all her thirtysomething-and-single anxiety on her younger sibling. “What a joy it must be to function as my sole outlet for a never-ending source of introspective blather,” Sam half-apologizes to Jess, in another self-conscious bit of lampshading. It’s a “joy” the audience must also shoulder, one breathlessly overwritten monologue at a time.

Perry moves this ensemble of miserable windbags through a cycle of baggy conversation, protracted speeches, and establishing shots of New York scored to a downbeat tinkle of piano. If this is a film about getting caught in a rut, he’s at least found a way to convey that idea structurally and stylistically, though that doesn’t make the repetitiveness any easier to bear. A ravenous New York cinephile who once manned the counter at Kim’s, the now-closed East Village rental hotspot, Perry has a video clerk’s appreciation for sacred cows: Cassavetes, Polanski, Wes Anderson. He’s modeled Golden Exits on the depressive 1970s familial-and-marital-strife classics of Bergman—or perhaps more accurately, on the Woody Allen version of the same, which took the Swedish director’s cries and whispers and funneled them through a neurotically New York sensibility. But if Perry’s last film, the throwback psychodrama Queen Of Earth, used Bergman worship as a jumping off point for its own genre games, Golden Exits is just a tin-eared imitation: Interiors remade as a stilted exercise.

Plopped at the center of the film’s gallery of domestic sad-sacks is Browning’s heroine, who Perry understands as a disruptive force, an obscure object of desire, a symbol of lost youth and possibility—basically, as anything but an actual character. Does she have a life outside of the small, cramped workspace she shares with her over-the-hill boss/admirer? Truthfully, Golden Exits is fuzzy on everyone’s details; for a film that pivots around the archiving of a life (creating a timeline is essential, Nick insists), it doesn’t animate the personal histories of its characters—the deep animosity, for one example, between Nick and Gwen, who place Naomi at the center of their passive-aggressive skirmishes. The film’s depiction of Brooklyn as a very small world, populated by only a handful of lost souls, seems more informed by Nick’s insular existence, which he happily admits is limited to a few blocks of real estate. But with a focus so narrow, shouldn’t Golden Exits be granular and specific, not vague?

At the same time, this is a drama that lays out all its themes in a neat row, leaving nothing to implication when it can simply have its cast discuss it all aloud, in endless, mopey soliloquies, sometimes exchanged by characters who have only just met. (Even the title gets blatantly explained; it refers to the clean endpoint one can achieve in all relationships except those between family.) Such a stylized approach could be galvanizing, especially when applied to humdrum bohemian lives, if Perry had a knack for the kind of self-reflective pontification in which his characters relentlessly indulge. But the writer-director mostly reduces his stellar performers to automatons, playacting dissatisfaction. Schwartzman, who did some of the sharpest work of his career in Listen Up Philip, fares best, mostly by virtue of getting to deliver the funniest lines—the lone traces, really, of the caustic wit the filmmaker has intentionally tabled, suppressing his comic instincts as thoroughly as Woody did in Interiors. But Parker also deserves some kind of sympathy prize, at least, for wrestling with Perry’s purplest dialogue. She does about the best anyone could with mouthfuls like “Love, jealousy, and deficiency, all wrapped up in a genetically bonded inability to ever express the concurrent depth of these feelings.”

The main thing Golden Exits has going for it is frequent Perry collaborator Sean Price Williams, the hotshot cinematographer responsible, most recently, for the invasive, expressive camerawork in Good Time. Shooting on rare-these-days 16mm, he gives the movie a sun-streaked springtime haziness—a quality of light, at once heavenly and earthy, that contrasts productively with the drab, grueling reality of the characters’ lives. He also keeps finding interesting new ways to capture Perry’s rambling tête-à-têtes, including an image Bergman himself might have commissioned: Sevigny, back to the camera, staring across a long den at the back of her husband’s head, distance and direction amplifying the disconnect between them. It communicates the, well, interiors of these characters better and more efficiently than any of the emotionally expository verbiage. Still, Perry’s gauntlet of gab does provide stray moments of self-awareness. Forget Naomi’s cute celebration of films about ordinary people. For a more accurate auto-description, look to a later line: “This is all so boring. There’s nothing to fixate on.”