Alexander Payne thinks too small with his Matt Damon shrinking comedy Downsizing

Alexander Payne’s science-fiction comedy Downsizing is less a fully formed satire than a clever idea stuck in first draft and stretched uncomfortably to feature length. From a distance, it looks like a major departure. Who, after all, expected a bona fide special-effects movie from the writer-director of Sideways and Nebraska? To tell the fantastical story of a world where humans shrink themselves to rodent size, mostly to increase their wealth, Payne has definitely strayed out of his comfort zone of ambling road-trip foibles and drab Midwestern tragicomedy. But though it might be tempting to celebrate Downsizing as an ambitious change of pace, the ambition is more of an optical illusion, a trick of forced perspective: The closer you get to the movie, the more you realize that Payne has devised an audacious conceit—a Swiftian high concept—and then let it go to waste.

It’s a shame, because there’s a lot of promise in the basic premise. Downsizing is set about 10 years after the invention, by quixotic Norwegian scientists, of a miracle technology, designed to solve the planet’s intensifying overpopulation problem. Yes, it’s a real-life shrink ray and people all over the world have begun willfully, permanently scaling themselves down to around five inches tall. Is this a utopian vision of a future where everyone’s suddenly grown an environmental conscience? Not so much. As it turns out, living large now means living small: Because everything’s cheaper at 1/100th of its normal size, money goes much further for the diminutive. Any middle-class wage slave can afford a mansion the size of a dollhouse—the trick is, you have to be little enough to live there. This is Downsizing’s best, sharpest joke: a withering metaphor for the insane lengths people will go to for material possession or even just the feeling of upward mobility.

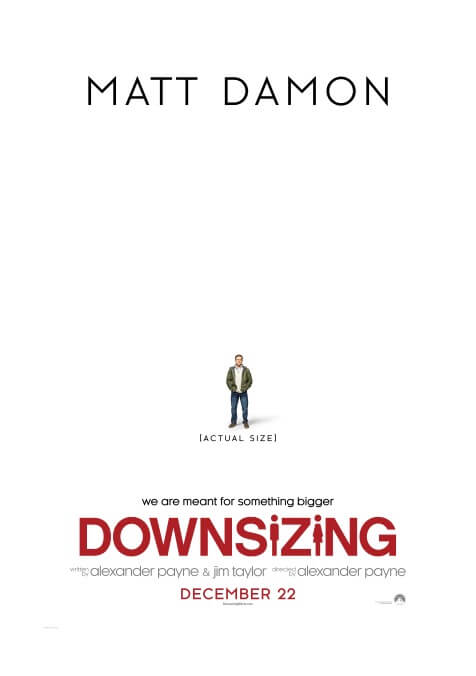

Into this brave new world of pint-sized social climbers, Payne drops another of his quintessentially Middle-American schlubs: occupational therapist Paul Safranek, played by a doughy, convincingly ordinary Matt Damon. Paul and his wife, Audrey (Kristen Wiig), live an unglamorous suburban life, struggling to pay bills and yearning for something more. That, of course, makes them the target demographic for “downsizing,” which Payne depicts as both a routine medical procedure and, essentially, a timeshare purchase. It should come as no great surprise that Paul, seduced by the promise of luxury, ends up taking the leap, dwindling to pocket size, and relocating to a kind of miniature gated community called Leisure Land Estates. This being a film by Alexander Payne, who’s made a career dramatizing middle-class dissatisfaction, it also probably goes without saying that Paul’s dream life in his Barbie dream mansion doesn’t turn out exactly how he hoped.

Downsizing gets by for a while on droll nonchalance in the face of sci-fi outlandishness; the film’s effects (lots of trick shots and in-camera wizardry) have been mostly applied to mundane dialogue scenes, which is a pretty good joke at the expense of anyone expecting the guy who made About Schmidt to go full Ant Man. Yet Payne doesn’t just subvert expectations about where his movie might be headed. He perversely ignores the endless visual, conceptual, and narrative possibilities of a world of tiny people. It’s at Leisure Land that the film loses the thread. Paul, lonely and depressed, ends up living below a rich European hedonist played, with the usual lack of restraint, by Christoph Waltz. He also ends up bonding with Ngoc Lan Tran (Hong Chau), a one-legged Vietnamese dissident who opens his eyes to the class divisions that exist even in their domed paradise. Payne plays the character’s pidgin English for broad, borderline racist humor, while also supplying her with not one but two bathetic tearjerker monologues. It’s the filmmaker’s worst impulses manifested in a single stereotypical figure: someone to be laughed at, then pitied.

Damon does supply a certain bruised dignity, as though he were starring in a midlife-crisis remake of The Incredible Shrinking Man. (One also thinks, vaguely and occasionally, of Behind The Candelabra, where the actor played another dejected man wrestling with his regret about an irreversible physical transformation.) But the film never lets Paul’s existential ennui breathe, and that’s partially because it never decides upon the movie it wants to be: As the plot zigzags off in a gooier direction, into an earnest eco drama about one’s place in the fight for the planet, the fact that we’re watching characters no taller than thumbs becomes weirdly incidental. Downsizing, in other words, doesn’t just squander its magical-realist premise. It kind of forgets about it. Maybe that’s Payne’s seriocomic point: that even an impossible development like voluntary shrinking would become just another facet of modern life, with its haves and have-nots. But it’s still hard not to daydream about what a filmmaker with, well, a bigger imagination might do with this big idea.