The inspiration is The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio’s medieval short story collection, an enduring episodic chronicle of hijinks, romance, and sexual misadventure during the time of the Black Death. Preserving the irreverence but tweaking the vernacular of the text, writer-director Jeff Baena (Joshy, Life After Beth) envisions his primitive religious backdrop as a kind of proto-boarding school, where the young nuns of the congregation bristle restlessly against the paltry meals, menial chores, and general devout tedium of their daily routine. Plaza’s Fernanda, a caustic eye-rolling hipster born eons too early, sneaks out to get into mischief, using a perpetually escaping donkey as her excuse. Uptight wallflower Genevra (a priceless Kate Micucci) tattles relentlessly on the other women, reporting every transgression to Sister Marea (Molly Shannon, playing her dutiful piousness almost totally straight—she’s the only character here that could actually exist in the 1300s). And Alessandra (Alison Brie), the closest the convent has to a spoiled rich kid, daydreams about being whisked away and married, but that would depend on her father shelling out for a decent dowry.

If the plague doesn’t kill them, the boredom will. Thankfully, like some kinky miracle, in comes a newcomer to disrupt the stifling sameness: strapping deaf-mute groundskeeper Masseto (Dave Franco), who’s actually neither deaf nor mute, but pretends to be both in order to lay low at the convent, beyond the reach of the lord (Nick Offerman) he’s been cuckolding. The premise suggests an accidental parody of The Beguiled (either version), which also concerned a deceptive, on-the-lam stranger hiding among horny, religious, stir-crazy women. But The Little Hours isn’t really spoofing anything in particular, even if Baena’s flatly presentational direction—goosed by the occasional ’70s-style zoom and the hilarious Renaissance faire squareness of Dan Romer’s score—does sometimes recall the ascetic austerity of the classic religious almost-comedy The Flowers Of St. Francis. Nor does the film reach the go-for-broke hilarity of the Mel Brooks and Monty Python movies to which it’s been prematurely compared. Mostly, that’s because Baena keeps the shenanigans pitched to the more grounded, behavioral comic style of his actors. For those not tickled by the idea of 14th-century characters behaving like 21st-century ones, the laughs will ride solely on the cast.

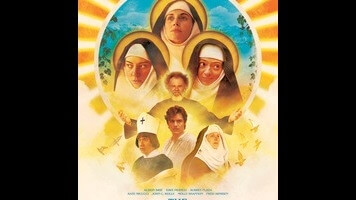

Thankfully, it’s all pros. The Little Hours generously provides everyone moments: Franco doing frantic pantomime, trying not to blow his cover even when his life is endangered; John C. Reilly, as the functionally alcoholic priest, getting sloshed before confession; Fred Armisen arriving late for a hysterical cameo as the exasperated bishop, who he plays like a peeved boss in from corporate to find the company in shambles. (His incredulous reactions during a long tally of the parish’s collective sins is a dressing down for the ages, Middle or otherwise.) But the movie belongs to its headlining trio, finding humor not just in broad shtick but also the relatable frustrations of these cooped-up young women, many forced into holy responsibility because they had no other options (a detail history and The Decameron can corroborate). When Plaza, Micucci, and Brie get smashed on stolen communion wine and perform a drunken sing-along of a wordless choral staple, like college girls sneaking booze past the RA and belting some radio anthem in their dorm, the true resonance of all this anachronism slips into focus: An itchy desire for a better life is something women of every century experience, regardless if their catalog of curses yet includes “fuck.”