Ally McBeal was more than dancing babies and inflammatory magazine covers

In 100 Episodes, The A.V. Club examines the shows that made it to that number, considering both how they advanced and reflected the medium and what contributed to their popularity and/or longevity. This entry covers Ally McBeal, which ran for five seasons and 112 episodes from 1997 to 2002, premiering 20 years ago on September 8, 1997.

Today it’s looked back on with a mixture of disdain and horror, so it’s tough to remember that Ally McBeal was one of the few bright spots among the fall TV premieres of 1997. Granted, its competition included Veronica’s Closet, the family sitcom Built To Last (it wasn’t), and Meego, in which Bronson Pinchot portrayed an alien. Many of its contemporaries didn’t even last two seasons, let alone five. But there was very little stability over the course of that run, and the show Ally McBeal became bore little resemblance to the one it started as—though it managed to break a few boundaries and pick up its share of awards in the process.

Former lawyer David E. Kelley—who already had Chicago Hope and The Practice on his plate—was tasked by Fox with creating a show about beautiful, successful people. To his credit, Ally McBeal turned out to be more than Melrose Place: The Corporate Years, casting New York stage actress Calista Flockhart as the young associate who goes to work at the Boston law firm of Cage And Fish, where she encounters the lost love of her life, Billy Thomas (Gil Bellows). Kelley realized his show’s early promise by turning Ally into a Walter Mitty of sorts: Bizarre, fantastical asides punctuated the show’s concepts and offered striking visuals not seen on other shows of the time. When Ally learns that Billy is married, she’s hit in the heart with arrows. When Billy suggests coffee, she pictures them frolicking naked in a giant coffee cup. When she tells us in voice-over narration (a device that gained ubiquity on network comedies in Ally McBeal’s wake) that she always feels like a little kid in client meetings, she’s then shown as a child, swinging her legs in a giant chair.

On the opposite end of the spectrum was the dancing baby that shows up to personify Ally’s rapidly progressing biological clock. A 3-D animation that was one of the earliest viral videos, the cha-cha-ing infant was thrust into the mainstream thanks to its appearance in Ally McBeal’s 12th episode, “Cro-Magnon.” “Cro-Magnon” aired at the dovetailing of the show’s popularity and the animation’s, and that sequence—set to Blue Swede’s recording of “Hooked On A Feeling”—came to represent the show’s quirky flourishes in the public imagination. The dancing baby later manifested on the show as a cupid and a demon, and when Ally haters pop up, it’s one thing they can easily point to.

The other specters haunting the show’s legacy arrived in time for its second season, which went on to win the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series. On June 29, 1998, the cover of Time magazine read “Is feminism dead?” The headline was accompanied by a progression of faces: Suffragette Susan B. Anthony, author of The Feminine Mystique Betty Friedan, Ms. magazine co-founder Gloria Steinem, and fictional Beantown attorney Ally McBeal. The words “apples” and “oranges” come to mind, even as writer Ginia Bellafante railed against the character, calling her ditzy and “in charge of nothing, least of all her emotional life.” A few months later, at the 50th Primetime Emmy Awards, Flockhart wore a gown that exposed her back—and a good portion of her skeletal structure. The resulting uproar led to another cover story, this time in People, and speculation about her and her co-stars’ weights entered the conversation around the show.

Despite these controversies, when the show was at the peak of its powers, it was Ally’s love life, not her politics or looks, that most consumed her and her viewers. Even her court cases often found parallels to her romantic life, from a female broadcaster suing her employer after being fired in favor of a younger model, or a lovestruck high-schooler trying to sue to get the object of his affection to go to prom with him. Throughout, Ally pined for Billy as she serial-dated “every guy in Boston”: a strapping Jesse L. Martin; Michael Vartan and William Russ as a father and son she dated simultaneously; even Jon Bon Jovi as a nanny. Ally never found true love again, but maybe that wasn’t the point.

The point, in fact, may be hard to pin down, as nearly every episode of the series was written by David E. Kelley. What did Kelley have to say about the plight of twentysomething women in the late ’90s? Turns out, a lot. I’m almost exactly the same age as Ally McBeal, and I found many of her lines shockingly spot-on to my own relationship roller-coasters at the time, and it was that voice, more than anything, that kept me glued to my TV every Monday. Ally despairs to Billy about the laundry list of a life she was supposed to have: a house, three kids, and a husband who would tickle her feet. Instead, she wails, “I don’t even like my hair!” Another time she goes off on the list of professional things she wants to accomplish, before admitting, “I just want to get married first.” My friend and I who were watching together solemnly nodded in agreement. In our own serial-dating years, amid horrible stats about biological clocks and the improbability of later marriages, Ally McBeal somehow voiced what we were afraid to say out loud. We were ambitious, professional women, of course we were. But did we meet the person we were supposed to marry in college and just forget? As our summers filled up with more and more wedding invitations in a game that seemed like some insane version of relationship musical chairs, we could relate only too well to Ally having a breakdown in a bridal salon or being haunted by the dreaded dancing baby.

And my friends and I weren’t alone in almost immediately loving Ally McBeal. In his 1997 Entertainment Weekly review, Ken Tucker describes being threatened by female staffers who warned not to knock their new favorite show. Where else were women like myself going to find someone on TV who seemed to embody their own doubts and insecurities? Not on Melrose Place, and not on NBC’s slew of female-driven sitcoms (Caroline In The City, Suddenly Susan, the aforementioned Veronica’s Closet), which all seemed tinny in comparison to Flockhart’s open emotionality on Ally.

In a 1998 Washington Post interview, Dyan Cannon, who played Judge Jennifer “Whipper” Cone on the show, said this about Kelley:

This man understands the way a woman thinks. […] He takes the things most sacred, most poignant and makes fun of them. David’s writing gets under your skin. You’ll say the line and you’ll laugh—then 10 minutes later you’ll be thinking about it. It’s like a 10-course meal.

The concept of men who become known as “women’s directors” and writers go back to the days of George Cukor and The Women, and runs through the emotional comedy of James L. Brooks, who helped give characters like Mary Richards and Rhoda Morgenstern so much life. While he was writing Ally McBeal every week, Kelley was also writing The Practice, leading to an Emmy double dip in 1999: The year Ally McBeal took the top comedy prize, The Practice won Outstanding Drama Series. Maybe Ally allowed him to tap into his feminine side, while his masculine side was personified by Dylan McDermott’s Bobby Donnell. After his ’90s heyday, Kelley hit a bit of a slump, but it should be noted that he recently rebounded with the decidedly female-focused project of HBO’s prestigious, Emmy-nominated miniseries Big Little Lies.

But Ally McBeal was about more than just Ally McBeal. By season two, 10 principals were listed in the opening credits: Flockhart; Bellows; Courtney Thorne-Smith as Billy’s wife, Georgia; in addition to Jane Krakowski as snoopy assistant Elaine; songstress and soul of the show Vonda Shepard as herself; Lisa Nicole Carson as Ally’s roommate, Renee; Peter MacNicol and Greg Germann as partners Cage And Fish; and Lucy Liu and Portia De Rossi as mean girls Ling and Nelle. Unusual for a major drama, the female characters greatly outnumbered the men: Most seasons the male cast members would top out at three or four. You could say that Ling and Nelle were brought in as impossibly attractive foils to the male law partners. Extremely sexualized and ambitious, their characters were also acknowledged as not very nice, even compared to Ally, who was hardly a social paragon. Still, as a whole, these women were able to depict a wide variety of relationship types, not just the unrequited view from Ally’s side of the unisex bathroom mirror: married love, friendship, crushes, or just simple lust-fueled hookups.

Ally shared the Walter Mitty duties, too. That unisex bathroom became a sort of jungle gym, where John Cage would practice various dismounts. Musical numbers, internal or otherwise, were prevalent, as were catchphrases (“Fishism!” “Bygones!”) and courtroom stunts. Some of these were more successful than others: A particularly egregious season-four subplot had the office squicked out by co-worker Mark (James LeGros) dating a transgender woman, played by Lisa Edelstein, who still had her penis. The pronoun “it” is thrown around; the arc has aged very, very poorly.

And maybe Ally has, too. Her frequent whining, her inability to not fall over when she’s attracted to someone, her incessant stammers and lashing out at strangers on the sidewalk. Women in her age group may understand what she’s going through, like I did, but watching it now, even I wanted to yell at her to snap out of it at times. Ally’s main guiding force appeared to be her unfailing belief in love, but as most of us now know, love is the easy part. Fighting over whose turn it is to empty the dishwasher is the hard part. Who knows how Ally and Billy would have fared if they had ever moved on from that idealized romance, laced with the unifying powers of forbidden love and nostalgia?

She came close to having it all, but always seemed to face relationship roadblocks. Plotwise, the show got off to a strong start, but took a dangerous turn in the middle of season two when Ally and Billy actually kissed, crushing his relationship with Georgia and what little firm ground there was for the show to stand on. Therapist Tracey Ullman (one of the show’s many stunt-casted guest stars) helped the couple realize why they broke up in the first place, with Billy harshly stating that Ally was determined always to be unhappy, so that “love is wasted on you.” It took a while for the show to realign itself. In fact, Billy had to develop a personality-transforming brain tumor to break up the infernal triangle permanently, destroying the character by dying his hair blond and having him constantly followed by a string of Robert Palmer girls. He died in season three, leaving that year a bit of a mess; the show’s usual deluge of Emmy nominations slowed to a trickle.

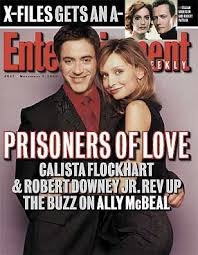

To bolster things in season four, Kelley took a risky move that (almost) paid off: hiring Robert Downey Jr. to play Ally’s new love interest, Larry Paul. Fresh out of Corcoran State Prison after a drug charge and parole violations, Downey was in the market for any kind of work, and proved to be an impressive fit on Ally McBeal, combining both quirk and a welcome sense of level-headedness. His chemistry with Flockhart was so strong that they soon made the cover of Entertainment Weekly, and Kelley made plans to have the couple marry at the end of season four. But it turned out that Downey’s drug problems weren’t quite over, so the penultimate episode of the season featured not Larry’s proposal, but a breakup. Oddly, the final episode of the season was still called, as it was originally planned, “The Wedding,” but the only person happy about that was baby Josh Groban, who now took center stage in the episode. Ally just gets accosted by a trio of singing mannequins. Downey, at least, won the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor.

Reflecting on Kelley’s TV trajectory for The A.V. Club in 2013, Stephen Bowie wrote, “The epic cast changes in Ally McBeal and Boston Public showed Kelley getting bored with characters almost as soon as he concocted them and writing in replacements faster than the audience could follow along.” Season five showed the worst of those whirlwind tendencies, starting off with a crop of new and unmemorable cast members. Julianne Nicholson and James Marsden showed up as a pair of lawyers with a past that resembled Ally and Billy’s; Regina Hall worked her way over from Larry Paul’s office to Fish And Cage. Meanwhile, Lucy Liu was off making a Charlie’s Angels movie, and MacNicol went down to recurring status. Lisa Nicole Carson had a mental breakdown, resulting in the discovery that she had bipolar disorder, and was written out of the show’s final season.

Most confounding of all, Kelley apparently decided that the key to Ally’s happiness was not romantic love, but maternal. A college egg donation resulted in the revelation that Ally is a mother, to young Maddie (Hayden Panettiere). Maddie also develops emotional problems: not very surprising, considering who her mother is, as Ally explains to her offspring that she just talks to her hallucinations sometimes. With ratings taking a dive and the end imminent, the show closes with Ally McBeal walking away from the family she chose in Boston to take care of her daughter in New York. (Of course ghost Billy shows up to say goodbye, only to disappear in a cloud of smoke; of course he shows up again onscreen just moments later.) Possibly Kelley was inspired by his own wife, Michelle Pfeiffer, who had adopted a child on her own before the two got married. Maybe he thought that Ally needed to experience some selfless love before she could ever really love anyone else. But the ending was a bit of a letdown, with even Ally sounding dubious about everything working out.

Twenty years later, Ally McBeal stands as an anomaly, a show defined as much by the talk it stirred up in the real world as by the things that happened in its own heightened reality. But a second look shows Kelley really trying to stretch within his small-screen boundaries—he is the guy who famously pushed Rosalind down an elevator shaft on L.A. Law, after all. Ally McBeal bridged the gap between TV genres, harkening back to ’80s dramedies like The Days And Nights Of Molly Dodd and Moonlighting while setting the stage for the modern-day, category-busting likes of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Girls. Whether Ally was an insane figment of a male writer’s imagination or a mouthpiece for her generation depends on how you look at it; my friends and I leaned toward the latter, happy with our careers and fighting with our hair as we hoped for love to again invade our lives, as far away as that sometimes seemed.

It’s telling that nearly every member of that massive cast can still be seen on TV in some form. Peter MacNicol is still picking up awards nominations on Veep, and Lucy Liu brings Ling’s stone-faced deliberation to the role of Watson on CBS’s Elementary. Flockhart had a successful run on Brothers & Sisters, a show where she could be more a part of the ensemble and less the center of attention.

More recently, she moved to Supergirl, ruling the roost as Kara Danvers’ boss, Cat Grant. Her role has been reduced as a result of the show moving production from Los Angeles to Vancouver, but even in more brief glimpses, it’s a joy to watch the formerly stammering Flockhart as a formidable badass who is trying to whip the eponymous Kryptonian into shape. When Cat dubs Kara’s alter ego Supergirl, Kara blanches. Cat rails at her, “What do you think is so bad about ‘girl’? Huh? I’m a girl. And your boss, and powerful, and rich, and hot and smart. So if you perceive ‘Supergirl’ as anything less than excellent, isn’t the real problem you?” Ally McBeal was also (relatively) powerful and rich and definitely hot and smart. So why would that make her character so threatening? Cat’s line is like a 20-years-late defense of Ally.

When Kara despairs over her love life, Ally-style, there’s another callback to Flockhart’s most famous role. Cat tells her charge, “The thing that makes women strong is that we have the guts to be vulnerable. We have the ability to feel the depths of our emotion, and we know that we will walk through it to the other side.” Time magazine and many others despised Ally’s vulnerability and seeming weakness, while fans of the show and people who could relate recognized that it was her unceasing ability to wear her heart not just on her sleeve but wholly on the outside of her body that made her much stronger than she appeared. At the end of the show, Ally McBeal strode away from those romantic entanglements—but just like Cat describes, she still had the strength to walk through to the other side.