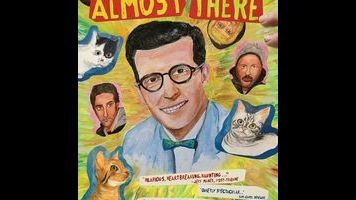

Almost There, made under the banner of Windy City-based doc shop Kartemquin Films (Hoop Dreams), gives Anton’s kitschy-colorful portraiture the requisite close-up, but the film quickly becomes more compelling as a protracted intervention than as an act of advocacy. Early on, Anton narrates illustrated snippets of his personal history—a back-of-head drilling by a football left him with lifelong nerve paralysis, and his mother yanked him out of art school after she discovered his female-form exercises in neatly crosshatched pen. It appears that for years this man, largely unequipped to take care of himself, has been doing just that.

Anton’s house, which he claims to have lived in since 1941 (his domineering mother died in 1981), is like something out of an evil-abode horror film: Entrants don masks on account of the mold, pipes gush water onto the floor, and hoarder’s flotsam has been repurposed to shore up the structure (at one point, a political-campaign yard sign can be seen as a patch in the ceiling). “I’m sorry but this is not an abandoned home,” reads a note on the front door warding off intruders. A carpenter brought in by the filmmakers confirms that the whole thing could collapse at any minute. Anton, who suffers through the winter in damp rooms devoid of heat, says he’d rather die there than uproot himself. However aghast he is, Rybicky can relate: The filmmaker’s adult brother, a visual artist with a history of mental illness himself, still lives at home with their mother in less-than-ideal (if not nearly comparable) conditions.

This family-history sidebar, given insufficient screen time, winds up feeling shoehorned in, but luckily the film as a whole soon transcends the concerned deference of the standard arts doc. Often stubborn and demanding, Anton nonetheless attracts a seemingly endless line of benefactors, be it Rybicky and Wickenden or fellow East Chicagoans like Dan McKern, a family man who enjoyed the company of the oddball artist until his ungratefulness became too much to bear. The film pivots on a revelation that in particular galls the filmmakers, who must come clean that their trust in their subject has led them to neglect adequate background research: The publicity surrounding the gallery show sheds light on details about Anton’s decades-ago brush with the law, a misdemeanor documented on a few easily microfilm-retrievable newspaper pages.

This turn of events allows Almost There to shift focus, nodding to evergreen issues with the outsider-art genre (artists “working outside the mainstream” haven’t always behaved like productive members of society) on its way to repositioning Anton as a lapsed member of the East Chicago community, ready to make good if he can. By this point, the filmmakers have also let go of the cliché they evidently thought they’d unearthed to begin with: the shut-in genius, his artistic integrity leading him to toil far from the public eye. After all, Peter Anton is too busy building his own eccentric myth—he is, most assuredly, at the center of his own universe—to conform to anybody else’s.