Aloft is a mopey bore, regardless if you figure out where it’s headed

Withholding crucial information can be a powerful dramatic tactic. Do it right, and the audience becomes glued to the screen, hanging on every potential clue, gobbling up each scrap of narrative data tossed its way. (Several films by the French director Claire Denis possess this allure.) The strategy can backfire, however, if the info being concealed is easily predicted—or, worse still, if it inspires no curiosity in the first place. Aloft, a fractured melodrama from the Peruvian writer-director Claudia Llosa (The Milk Of Sorrow), tracks two timelines in parallel, tiptoeing around the tragedy that links them. But even those incapable of getting ahead of the film’s big reveal, and hence reducing much of its runtime to a waiting game, will probably lose interest before all the cards are laid on the table. What’s really been withheld, in this dreary drag of a movie, is a reason to care.

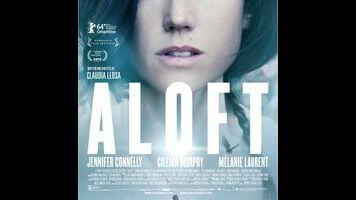

In the Arctic Circle, sullen single mother Nana (Jennifer Connelly) struggles to raise two young boys—saintly moppet Gully (Winta McGrath), afflicted with a terminal illness, and petulant older son Ivan (Zen McGrath), who dotes on his pet hawk. Out of viable medical options for her youngest, she seeks the assistance of a traveling faith healer, a boozy and amorous guru played, in the film’s only moments of faint levity, by opera singer and Certified Copy star William Shimell. After an incident involving the pet bird and a collapsing structure forged of sticks, the man comes to believe that Nana, skeptical of this whole belief system, has acquired his magic touch. Fast forward two decades and she’s embraced the life of a holy woman, inspiring her own flock of followers. Ivan, meanwhile, is now a hermetic falconer portrayed by Cillian Murphy, at his absolute broodiest. The film cuts back and forth from his tough childhood to scenes of him accompanying a documentary filmmaker (Mélanie Laurent) on a search for his estranged mother.

In its unyielding dourness, its nonlinear structure, and its vague symbolism—that soaring falcon surely represents something—Aloft often resembles one of the pre-fallout collaborations between director Alejandro González Iñárritu and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga. Except 21 Grams, for one example, at least had some visual panache, a little style to invigorate its miserablism. Here, Llosa films her actors—robbed of their charisma, saddled with characters as severe as the weather—in unvarying handheld close-up, the better to absorb the depressive vibes they’ve been instructed to constantly send. The filmmaker doesn’t even seem interested in whether Shimell’s shaman is a charlatan or the genuine article; such spiritual questions can’t compete with the more banal mystery of what drove a mother and son apart. After a while, all the avian imagery starts to feel less tedious than instructive, even heartening. We too can fly away from this frozen landscape of ennui and the boring sadsacks populating it.