America’s first female detective once saved Abraham Lincoln’s life

This week’s entry: Kate Warne

What it’s about: America’s first female detective. In 1856, 23-year-old Kate Warne walked into the Pinkerton Detective Agency—which had never hired a woman for anything other than clerical work—and walked out with a job as a detective. She had a successful career with the Pinkertons that included uncovering and foiling a plot to assassinate then-President-elect Abraham Lincoln, who she later worked for as a spy during the Civil War.

Biggest controversy: Virtually nothing is known of Warne before joining the Pinkertons. The only biographical details Wikipedia has is that she was born in Erin, New York, today a town of less than 2,000 people; and that she was already a widow at age 23 when she joined the Pinkertons. She never remarried, but is widely believed to have had a long-running affair with her married boss, Allan Pinkerton, founder of the detective agency that bore his name. (They often posed as husband and wife while on assignment.)

Strangest fact: While Warne may have been an accomplished detective and spy, her aliases were strictly at the Clark Kent-wearing-glasses level of deception. Wikipedia lists 12 aliases; every one of them is a very slight variation on her actual name. Her choice of first names were limited to Kate, Kay, and Kitty, and her fake last names included Warren, Waren, and her actual last name. Despite this, she was a remarkably successful detective and wartime spy, possibly because no one suspected a female detective in a world that rarely saw one.

Thing we were happiest to learn: Warne opened the door for other women. When she applied to the Pinkertons, she made a case not just for herself but also why women were well-suited to the job in general, asserting that they could go places men couldn’t, had an eye for detail, and that “men become braggarts when they are around women who encourage them to boast.” Within a few years of Warne’s hire, Pinkerton began a Female Detective Bureau, which Warne was the head of, and Pinkerton himself named her one of his five best detectives. Despite the success of Warne and other women working for the Pinkertons, America wouldn’t see its first female police officer until 1910.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: While Warne thrived in a dangerous profession, she only lived to be 34. The cause of death given on her gravestone is “congestion of the lungs.” She was buried in the Pinkerton family plot, and Allan Pinkerton ensured in his own will that her plot would never be disturbed.

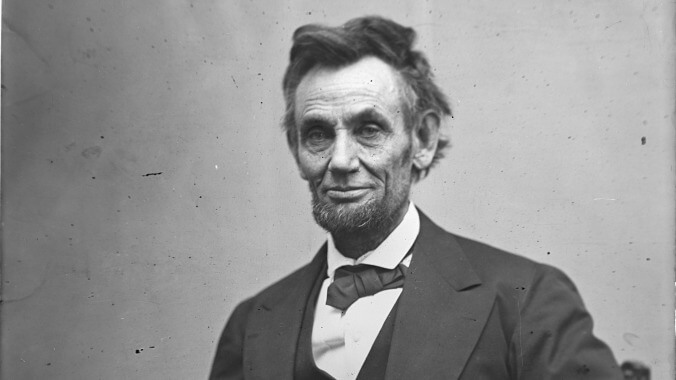

Also noteworthy: Mildly noteworthy was that Warne saved the life of Abraham Fucking Lincoln, and possibly the Union itself. In 1861, the Philadelphia, Wilmington And Baltimore Railroad hired the Pinkertons to investigate secessionists threatening the railroad. Pinkerton sent five agents, Warne among them. At this point, she had discovered aliases that weren’t her own last name, and under the guise of a Southern belle alternately named Mrs. Cherry or Mrs. M. Barley, she infiltrated pro-secession social gatherings and discovered that the plot wasn’t only against the railroad but also one of its passengers—President-elect Lincoln.

Warne was able to uncover key details about the plot, which involved Lincoln’s journey from his home of Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., for the inauguration. All southbound trains heading into D.C. made a transfer in Baltimore, which involved moving between the Calvert Street and Camden Street stations, a mile’s journey by carriage. Secessionists planned to stage a fight as Lincoln was boarding the carriage, distracting police (this was decades before the Secret Service would be formed), leaving Lincoln unprotected from a mob that planned to overrun his carriage and do their worst.

Lincoln took some convincing that his life was in danger, and even when he accepted the plot was real, refused to change his travel plans, which included a string of public appearances between Springfield and D.C. So Warne and Pinkerton hatched a plan. Lincoln excused himself early from his last public appearance, disguised himself as an invalid, and boarded a private train car Mrs. Cherry had booked for her “invalid brother.” Warne stayed up all night standing watch over the new president, whose identity was never suspected. Rather than transfer via carriage, Lincoln’s sleeping car itself was shifted to another train, which arrived in D.C. first thing in the morning. Warne’s overnight vigil is believed to have inspired the Pinkerton Agency’s slogan, “We never sleep.”

If the plot had succeeded, would vice-president-elect Hannibal Hamlin have been able to steer America through its darkest hour? Thanks to Warne, we didn’t have to find out.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: With Lincoln in office, Warne went to work for him as part of a network of American Civil War spies (one of whom we’ve already covered in this space). As soon as war broke out, General George McClellan asked Pinkerton to set up a military intelligence service—he enlisted Warne and two other agents to work directly with McClellan. As she did during the assassination plot, Warne would go undercover as a Southerner (often with Pinkerton posing as her husband) and mingle with Confederate society, digging for information she could then report back to McClellan.

Further down the Wormhole: One of the public events Lincoln refused to cancel involve raising the American flag in front of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Built in 1753 as Pennsylvania’s colonial statehouse, the Hall became one of America’s first landmarks, as it housed the writing and signing of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The latter was written in 1787 after America’s original system of governance, the Articles of Confederation, signed in the midst of the American Revolutionary War, proved unworkable.

Tenuously connected to the Revolutionary War, but listed in Wikipedia’s related topics, is the 1780 Gordon Riots. Lord George Gordon had passed the Papists Act of 1778, intended to reduce anti-Catholic discrimination, but London’s anti-Catholics were not pleased, and the country—already under the strain of fighting America, France, and Spain simultaneously with no major allies—erupted into violence. We know we’ve written about several British riots in recent columns, but it’s hard not to keep returning to the subject when some of them have names like the Nottingham Cheese Riot. While the Gordon Riots were the most destructive in London’s history, the riot 14 years earlier in Nottingham involved hundreds of cheese wheels being angrily rolled down the streets of town, so we’ll be revisiting the Great Cheese Riot next week.