American Crime: “Episode Eight”

How much do you have to know about a person before you feel comfortable making a value judgement about them? For most of us, it’s probably not much, a tendency only exacerbated by the internet age, where you’re able to know bits and pieces about millions of people at once, sorting them all 140 characters at a time or less. It’s innate, to a certain extent, the need to process information about strangers rapidly, to determine whether they’re friend or foe, a holdover from the evolutionary age where being slow to judge could result in being eaten by a bear. But how valuable is being so quick to size someone up now and, more importantly, how aware are we that we continue to do it?

We’ve discussed previously in these reviews how American Crime examines how often people are judged based wholly on appearance and even how those biases can be used to manipulate one into seeing something that isn’t necessarily there. With “Episode Eight,” the show begins digging into what it is on the other side of that judgement, specifically what happens when the judgement of others deeply deviates from how we see ourselves.

The center of this episode about judging a person based on their actions revolves, perhaps ironically, around Barb. From the beginning, Barb has been a difficult character who, despite a phenomenal performance by Felicity Huffman, sometimes struggles to appear as anything other than a two-dimensional bigot. That summation of Barb’s character is somewhat tongue in cheek, because what I realized in the middle of this episode, is that I don’t really know anything about Barb.

That’s not entirely true. What I know of Barb is a lot. I know that she had a shitty marriage to Russ and bore the burden of raising their two sons. I know that her life was difficult, that money was tight, and that during that time, she did the best that she could. She came away from that time with opinions about other people and her place in the world and she’s not shy about voicing them. Barb speaks to the truth of her world because she thinks it’s just that: truth. Facts. She is wary of the world and she misses her son and she doesn’t understand why no one cares as much as she does. But here’s what I honestly didn’t realize about Barb until “Episode Eight” spelled it out for me: Barb has no idea that she’s a racist.

It’s mind-boggling, really, to think of someone who speaks so carelessly and with so much hate being utterly surprised that other people think she’s a bigot. And the shock of the realization to her is brutal. She seems to have grown accustomed to the accusation being thrown at her by people who are biased or who don’t really know her but when the assumption comes from people she thought really knew her, understood her, she looks all more like a puppy who’s been rapped on the nose for misbehaving.

If Barb’s racism was accidental, does that make a difference? She’s certainly not comfortable being in league with her new friend the racial seperatist and intent matters but how much? There must be a blend between the judgement we level at others and that which they believe themselves to be, but at some point what Barb has to realize is that intent may be the difference between murder and manslaughter but at the end of the day, someone still ends up dead.

Barb’s not the only one facing these issues throughout the episode. Russ is struggling in the wake of losing his job, trying to convince Mark to convince Tom and Eve, to let him stay in Gwen and Matt’s house while he fixes it up for sale. He also tries to reach out to his work friend to talk but she wants nothing to do with him. Russ is suffering at the hands of his actions from years ago, his prison time, his lies, his absentee parenthood, and while he sees himself as a man completely different from that, it’s impossible for anyone else to see. He is what they say he is, whether he likes it or not.

Hector, too, was confronted with the judgement of his actions, in his case, by his ex-girlfriend who came to visit him in prison. She rails against Hector for abandoning her and his child while he made shallow excuses about not being able to give her what she needed and not being given a chance, before finally telling her that every time he tried to do good, it just ended up bad. Hector went to America and tried to do better but because of the snap judgements people made against his appearance, he was forced into a situation where people now make judgements about his poor choices.

How are these things balanced and how many people does it take to determine what kind of person you are? American Crime itself spoke about the dangers of snap judgements just a few episodes ago. Who decides what kind of person you are? How much of a say do you have in it? And ultimately, how do you reconcile who you think you are with how the world sees you?

Stray observations:

- The comments from last week really made me think while writing this review. It would seem that many people don’t believe Aubry’s accusations from last week and are happy to dismiss her in very harsh terms. She’s a difficult character, to be sure, but most everyone on the show is and this week demonstrated that the character is not beyond the ability for growth, calling her foster mother mom. As for the claims for abuse, I think it’s pretty obvious that it happened, as the show was laying the groundwork for it two, if not three episodes ago, something I referred to with dread in this review, as I found it to be a pretty cliche plot contrivance. That opinion comes not from anything character based but from 30 years of obsessively watching television and the ability to sniff out plot twists like a bloodhound.

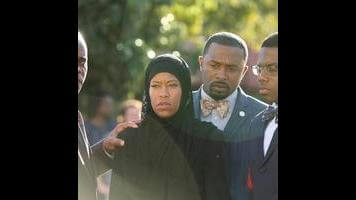

- Obviously the biggest event from the episode I wasn’t able to work into the review was the demonstration clash at the end. It was a very effectively shot sequence, that hearkened back to both Selma and the Ferguson protests of 2014 and the choice to, once the violence escalated, to pivot to shots broken up with black screens served to heighten the tension of the moment while also allowing the show a way to cut around the most sickening depictions of violence. That said, perhaps because of the absolutely impeccable work in Selma and the horrifying familiarity of Ferguson, the scene did read a bit like the best possible version of those things that could air on a network drama. It was worlds better than when The Good Wife tackled similar subject matter but still faltered because it could never really capture the muted horror of reality.

- I never thought I’d be moved by a Barb storyline, but her clear distress at being seen as a racist and her drive out to the railroad tracks made it very clear how disorienting it is to be perceived as something that you’re sure you’re not. She does end up with a gun by episode’s end but at this point I don’t know if she’ll use it against someone, have it used against her, or something I’d never considered before, use it on herself.

- Alonzo begging Tony to lie to the police and make up information to trade for his release was so depressing. Sadly, Tony has grown up to be the man that Alonzo always wanted him to be and refuses to incriminate a man who, very likely, may be just as innocent as he originally was. Heartbreaking all around.

- Equally moving was Carter and Aliyah discussing his plea deal. I want to be mad at Aliyah for not allowing Carter to take the plea but I truly believe that her terror that Carter would not survive inside his mind, inside of prison is genuine and she believe that the case being dismissed or him being found not guilty is the only real path to his freedom. Still. Anguish.