“This is all too big. Too much going on at once.” That’s how Mr. Nancy starts “Come To Jesus,” the season finale of American Gods. He looks up from his sewing machine and announces, “We should start with a story.”

A viewer who’s been waiting for the war of the gods—or for the show to reach the House On The Rock, or for Laura Moon to be resurrected, or for any of the other tantalizing goals of the season—can be forgiven for feeling, like Wednesday, that we haven’t got time for a story.

But Mr. Nancy says we do.

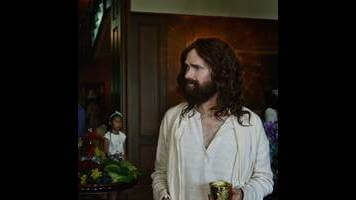

The lighting and framing of this scene fooled my eye at first. I thought Nancy was sitting behind Wednesday and Shadow as they idly watched his reflection in a mirror. But what I took to be the frame is a doorway; what I thought was a bright square of reflected light is instead the bright light over his tailor’s table. It’s a clever illusion that makes it look as if Wednesday and Shadow are seated before a screen—as if they’re watching the next best thing to a television. As if they’re us, watching the action unfold… except the action is a man (a god) placidly cutting and sewing pieces together, and even that repetitive action is broken by his insistence on telling us a story. Another story.

Throughout season one, Wednesday has asked Shadow variants of the question he asks again and again in “Come To Jesus”: “Do you have faith?”

The first season of American Gods is a leap of faith. It’s a leap of faith, if not an act of hubris, to convert a popular novel into a series, especially a popular fantasy novel with a sprawling story spread across a nation in different times and locales, with different casts of characters. It’s a leap of faith to pluck key episodes from the novel and tinker with them, upend them, even ignore them entirely in favor of new stories. It’s a leap of faith to let the weight of the show rest on the novel’s minor characters as heavily as it does on the protagonist and his boss. It’s a leap of faith to bank on the chemistry between an unrepentantly unlikeable corpse and a towering leprechaun, and it’s a leap of faith to anchor the season’s emotional core on it.

It’s a leap of faith to end the first season end with the gauntlet of war thrown down, to have planned out this season before knowing for certain that American Gods would return for a second. It’s a leap of faith to end at a crisis point, and even more so to end at a crisis point that doesn’t appear in the novel.

It’s a leap of faith, and it’s more than daring. It’s dizzying, as dizzying as the frolics of the bunnies who chase after Wednesday and Shadow as they drive through Kentucky. As dizzying as the shot that pulls back to show vivid floral borders swirling around a stately house, as dizzying as food stylist Janice Poon’s dazzling buffet of multicolored macarons, hoops of roasted rabbits adorned with corn-husk ears, deviled eggs tinted pastel, and rainbows of cocktails in gold-rimmed stemware. As dizzying as Shadow’s realization that all the men around him at the Easter brunch don’t just look like Jesus Christ; they are Jesus Christ, every last one of them.

Or, to put it in bleaker terms, it’s as dizzying as the chasm between the softness of Media’s cotton-candy pink garden-party gown and the stony cold in her eyes, between the sweetness of her tone and the poisonous threats she drizzles out. As dizzying as the ring of faceless dancers who weave threateningly around Easter herself (Kristin Chenoweth) as the eons-old goddess of spring bounty faces off with Media. As dizzying as the winds that sweep the countryside when the embodiment of the dawn casts off her prim masquerade as Easter and reclaims her power as Ostara. As dizzying as the realization that claiming her power means withering all the plenty she’s produced and starving a nation into faith.

The first season of American Gods is one long leap of faith, and in the season finale, almost all that faith is rewarded.

It’s not just the daring storytelling—the willingness to break from the established stories of the novel, or the riskiness of a first-season cliffhanger before season two is signed—or the lush, ripe settings and complex depictions of its characters that makes American Gods so rewarding. Amid its brashness and brightness, American Gods is also sneakily subtle.

The parallels between characters continue, quietly connecting these sometimes seemingly disconnected tales and hinting at what might be ahead… or underneath. When Bilquis rejects a call from Mr. World’s mouthpiece, Technical Boy, we see his number is listed as “The Man.” When Easter questions Mad Sweeney, she asks, “You still working for the man?” and you can almost hear the capitalization in her tone. Mad Sweeney reminds Laura that Shadow doesn’t matter, “he just happens to be the guy,” much as Media tells Wednesday, “You don’t matter. Not very much, not anymore.”

These small harmonies and hints add up, whether you’re consciously registering them or not. They help to anchor the action and portrayals. They help to give background and depth to the pageant unfolding on the screen. They help to earn a viewer’s faith.

I qualified my faith, and I have reasons. In my review of “Prayer For Mad Sweeney,” I hoped we’d see other gods similar treatment for other gods who’ve been slighted this season, and “Come To Jesus” delivers that, in its way. Bilquis’ backstory is powerful and affecting, and Disco Bilquis is truly magnificent.

Bilquis has power. That power is derived from her sexuality, from her sensuality, and—this is the stumbling block—from nothing more that we are allowed to see. She is the only goddess presented almost always in a state of undress. Even Ostara, whose power is fertility, is never presented without her finery. Bilquis is shown grinding and panting; Easter, at most, lets her hair down.

Bilquis is the only goddess seen sleeping on the street. Though the gods we saw in Chicago are poverty-stricken, Bilquis is the only one shown pushing a shopping cart, having forgotten herself entirely. She’s the only god the writers have chosen to show with sores and sickness.

Most strikingly, Bilquis is almost entirely without a voice. She drops a sentence here or there, but unlike a lesser creature like Mad Sweeney, or even a human like Laura Moon, instead of acting out her own story in her own voice, she’s shown from a distance, her fortunes and disasters narrated by Mr. Nancy. Yetide Badaki makes Bilquis’ expressions—her longing looks, her confident gaze, her pained yearning—speak loudly, and Orlando Jones delivers her story with unsurprising aplomb. But a powerful goddess deserves to articulate her own history.

By and large, American Gods’ first season has cleverly diversified the characters and voices who animate this season. There have been missteps, like the unintentional distancing and diminishing of Bilquis or the sidelining or Mr. Ibis and Mr. Jacquel. But the expanded presence of Laura Moon, of Salim, of Ostara—these all hint that creators Michael Green and Bryan Fuller, as well as their writers’ room, are devoted to making American Gods as diverse as the nation it portrays. If they deliver on that promise more fully in the second season? Well, that would be dizzying indeed. That would fully reward my faith.

That opening scene intentionally creates an illusion, and it’s Mr. Nancy’s step throw his doorway and onto his own tailor’s pedestal that destroys the illusion. With a snap of his fingers, he breaks that trickery of light and framing, destroys the distance between viewer and storyteller. ‘Once upon a time—,’” he begins, breaking off immediately to compliment his own story. “See? It sounds good already.” Orlando Jones spikes the camera with a knowing look as he adds, “You’re hooked.”

As American Gods ends its first season, it turns out this first season was mostly prelude, mostly a dressed-up version of Mr. Nancy’s “Once upon a time.” But he’s right. It does sound good already. And I’m hooked.

Stray observations

- Squeezing Mad Sweeney’s scrotum, Laura threatens to “squeeze ’em straight out of the sac. It’ll be kind of like shucking peas”. It’s a sly reference to the peas elderly Essie Tregowan is shucking when Mad Sweeney comes for her; in “Prayer For Mad Sweeney,” she’s changed to Essie MacGowan and the peas are changed to apples.

- Though the episode is entitled “Come To Jesus,” the flock of Jesus figures don’t figure in it much. As Jesus Prime, Jeremy Davies is a perfect pontiff, his expression an ambiguous mixture of wisdom, sorrow, peace, patience, and just a hint of petulance. When Wednesday spits out unwelcome truths about Easter’s subordination to the many Christs, Jesus Prime takes the moment to make it all about him. “I feel terrible about this,” he said, his voice breaking, as he martyrs himself once again.

- Laura Moon’s disintegration is getting grotesquely real. As the season ends, we see her standing in full daylight, her eyes dull and darkly circled, her skin mottled and ghastly. Even her speech is slurred, as if her tongue has slackened in her mouth.

- In an interview with Esther Zuckerman, Kristin Chenoweth discusses her preparation for this role and delves into some fascinating details about her character’s mannerisms and appearance.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)