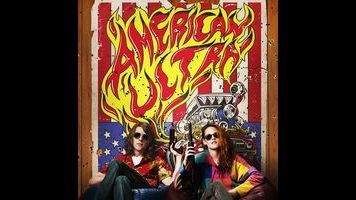

American Ultra has gruesome fun with a one-joke premise

In American Ultra—a stoned, occasionally gruesome riff on The Bourne Identity, flavored with a touch of First Blood and Burn After Reading—a small-town pothead lives blissfully unaware of his past as a brainwashed super-soldier, programmed by the CIA to be able to kill anyone using anything. Then, an intra-agency power struggle results in a termination order, and within a few hours our hapless hero finds himself in the parking lot of the Cash-N-Carry, having just killed two black-ops gunmen using nothing more than a dull spoon and a cup of ramen noodles, with no understanding of how he did it or why. Operating within the logic of severely stoned paranoia, he concludes that he must be a robot.

Arriving in theaters in the dog-day dumping ground of August, American Ultra is one of those geeky genre mishmashes that’s very clever about being dumb. Written by Max Landis (Chronicle), the movie takes a one-joke premise—“What if Jason Bourne couldn’t remember his past because he was baked all the time?”—and gives it more layers of shading than a viewer probably has any right to expect. Nima Nourizadeh’s direction skews eclectic: overhead shots, extreme telephoto close-ups, quasi-ironic slow-mo sequences, digitally composited long takes. The violence is exaggerated into explosive blood spurts and doors ripped apart by gunfire—the stuff of scrappier genre fare, in which the viewer gets hooked on the fun the filmmakers must have had in making it. It’s demented, occasionally inspired, and often very funny.

But oddly, the one thing American Ultra isn’t very good at is being a straightforward action flick, despite a conceptually spot-on climactic set piece that finds Mike Howell (Jesse Eisenberg, sporting luxuriant hair extensions) dispatching a small army of goons using whatever he can find on the shelves of a big-box store. Perhaps this is the inevitable trade-off of opting for an actor who could credibly play an anxious stoner over one who could play a world-class killer. As Eisenberg awkwardly elbows his way between stuntmen, the only thing that registers is the goofiness of it all—which is sort of the point.

In a minor coup of casting, Topher Grace plays the antagonist, effectively pitting against each other two actors who have a knack for playing beta-male pricks. Given a temporary promotion, CIA careerist Yates (Grace) decides to make his position permanent by offing Mike, the only survivor of his predecessor’s pet program. Mike has been living for the past five years in a fictional West Virginia community of Liman (one of the movie’s more obvious nods to its source material), prevented from leaving by severe panic attacks that are actually the product of a brainwashing failsafe. He spends his days working the register at a convenience store and doodling violent comics about a NASA test chimp named Apollo Ape—expressions of his repressed past as an assassin.

Whatever free time he has, he spends with Phoebe (Kristen Stewart), his long-time girlfriend, with whom he shares a dumpy bungalow-style house, a set of matching tattoos, and a preference for spending every day in a haze of pot smoke. Somehow, the dynamic between the two—defined by the comfortable body language of the actors and by a few unexpected notes of eroticism—feels more credible than most on-screen relationships in recent memory; who knows whether that speaks more to American Ultra’s particular qualities, or to the state of mainstream American film as a whole. What should, by any right, be nothing more a corny through-line (see: the engagement ring Mike carries around, waiting for the right moment), becomes something like an honest-to-God emotional center.

If American Ultra has one big trick up its sleeve, it’s these small gestures of nuance. It turns a cackling maniac henchman into a figure of uneasy sympathy and rarely misses an opportunity to remind the viewer that the uniformed goons Mike is facing aren’t there by choice. Yates and Mike are doubles, both going against their superiors. In the movie’s anti-authoritarian worldview—which is complicated by an ending that could either be interpreted as cynical or a cop-out—which side you’re on ultimately comes to the question of how willing you are to follow an order you don’t agree with, and why.