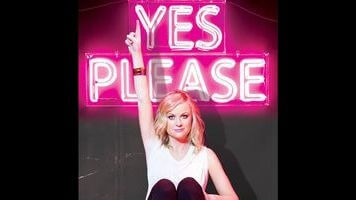

Amy Poehler’s delightful debut book is a group effort

The path to Amy Poehler’s first book, Yes Please, seemingly runs through a memorable cameo in Tina Fey’s 2011 autobiography, Bossypants. Amid the anecdotes from Fey’s time on Saturday Night Live, she recalls Poehler telling a bawdy joke, Jimmy Fallon reacting negatively to that joke, and Poehler meeting that reaction with righteous fury. “I don’t fucking care if you like it,” she responds—a rallying cry that temporarily steals the book for Poehler and sets up the “go your own way” philosophies that power Yes Please.

Ever the gracious ensemble player, Poehler pays that Bossypants favor forward in Yes Please, handing over pages to her parents, former “Weekend Update” co-anchor Seth Meyers, and soon-to-be former Parks And Recreation showrunner Michael Schur. (Fey doesn’t contribute, but she receives a chapter-long tribute and an acrostic poem in her honor, which Poehler teasingly calls “arguably the laziest form of writing.”) It’s a distinct approach to autobiography—and as a hybrid of memoir, essay collection, and Life’s Little Instruction Book, Yes Please is undeniably distinct—one grounded in the type of improv-comedy teachings the author has passed down as a founding member of the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre. Poehler is Yes Please’s headlining act, but many of her anecdotes are about projects, communities, and achievements in which she was but one participant.

It’s clear from the start that’s her preferred mode of creation: References to the difficulties of writing a book and the loneliness of an author’s experience are peppered throughout Yes Please. Those might prove deflating were it not for the Leslie Knope-esque “yes we can” spirit that pervades all three sections and their affirmational headings: “Say Whatever You Want,” “Do Whatever You Like,” and “Be Whoever You Are.” In his annotations to the chapter about Parks And Rec, Schur refers to Poehler’s “supreme sincerity,” but even before that there’s no doubting Yes Please as a completely sincere venture. Poehler’s prose is direct and matter of fact; there’s a distinctly no-bullshit sense to the dispatches from her career and home life. Particularly in the latter, which, without digging around in the dirt, doesn’t dance around the author’s 10-year-marriage and eventual separation. The end of that chapter in her life opens up one of Yes Please’s most playfully dark passage: A six-item listicle in miniature titled “My Books On Divorce.”

The title of one theoretical volume on divorce, Get Over It! (But Not Too Fast!), demonstrates a central contradiction within Yes Please. For a book that offers first-time mothers the pragmatic motto “Good for her! Not for me,” Yes Please can be a little prescriptive with its advice. Poehler makes no claims to being a guru or a life coach, but the daughter of two schoolteachers who (directly or indirectly) taught a whole generation of comics how to be funny tends to go thick on the rules and guidelines. Part of that is a function of her straightforward writing style, which doesn’t deal in gray areas; another is a result of Yes Please’s sense of humor. If any of her thoughts on motherhood come across as hyperbolic, it just might be that Poehler is amused that anyone might look to her for this type of guidance.

Hopping from subject to subject and mixing multiple perspectives and varying tones (a hand-scrawled list headlined “Reasons We Cry On An Airplane” here; a report from the author’s humanitarian trip to Haiti there), Yes Please is a breezy read that runs on its own internal logic, mimicking the stream-of-consciousness flow of improvisational comedy. While delving into her bad sleep habits in one chapter, Poehler provides a succinct summary of her book’s structure: “As soon as I become prone, my head will begin to unpack. My mind will turn on and start to hum, which is the opposite of what you need when you begin to switch off. It is as if I were waiting the whole day for this moment.” At times it feels like the book captures Poehler’s mind as it starts to unpack, as if she’d been waiting her whole life to relate these stories about her Boston-area childhood, breaking during a “Debbie Downer” sketch, and sitting in Bono’s lap while winning a Golden Globe. The book is best viewed through this filter, like opening a door in Poehler’s head and watching all of the memories, opinions, and insight pour out. And if you don’t like it? Well, the author has a few choice words on that subject.