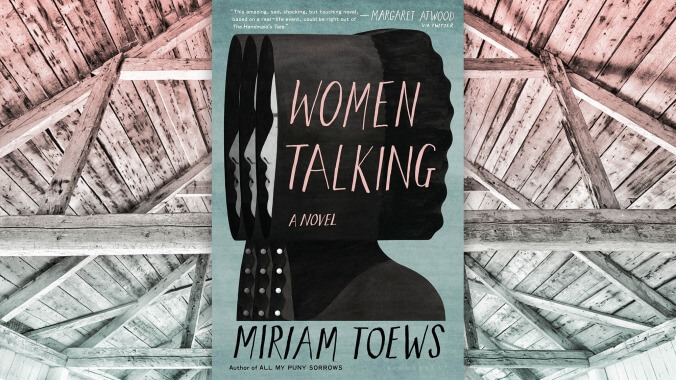

An awful crime gets Women Talking in one of the first great novels of the year

Image: Graphic: Rebecca Fassola

“How would you feel if in your entire lifetime it had never mattered what you thought?” For the man being asked in Miriam Toews’ new novel, Women Talking, the question is hypothetical. For the woman asking, it’s anything but. She lives in Molotschna, a Mennonite colony in South America, where she and the community’s other female members are treated as second-class citizens—subservient to their husbands, denied education, valued primarily for bearing children—and where, for the past four years, more than 300 of them have been repeatedly raped. The women would wake in the morning bloodied and in pain, with no memory of the night before, their claims dismissed by the bishop as “wild female imagination,” then explained as the devil punishing them for their sins.

Based on real events in Bolivia’s Manitoba colony in the mid- to late-2000s, Women Talking begins with the discovery that eight men in Molotschna—brothers and cousins, fathers and husbands—have been spraying the women’s houses with animal tranquilizer, entering their homes, and violating them. Insulated by design, Molotschna is self-policed, and action is only taken when one woman, whose 3-year-old daughter was among the victims, goes after the men with a scythe. It is for their own safety that the attackers have been arrested, and while the other men travel to the city to post bail, eight of the women—representing three generations from two families—convene in a barn’s loft to decide how to respond: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave.

In a narrative so sharp it could draw blood, Women Talking asks an immense, weighty question: How do women who have lived their entire lives in a society that severely limits their agency act when suddenly needing to exercise it? In grappling with this question, Toews, who was raised in a Mennonite town in Canada, has written a heated, heartbreaking story at once fundamental and contemporary.

Over the course of two days, Toews’ eight angry women debate and bicker, reason and wander. They explore each corner of their argument through Socratic dialogue, knocking against the confines of their religion in the process. Will they get into heaven if they don’t forgive their attackers? Can they remain pacifists when surrounded by men who have raped them and their children? Like the clean plaits the teenage girls of the colony braid their hair into, the novel is split perfectly in half: the first, the women’s discussion; the second, their arrival at a decision and plan to implement it. Talk then action, theory then praxis. When part two arrives, the pace quickens, dizzyingly so, the speed at once anxiety-provoking and exhilarating. The book’s passionate ideology can make it feel like a manifesto being composed in real time, but Women Talking is not a polemic dressed up as fiction. This essential novel is as electrifyingly alive for its masterful storytelling as for its clear, pointed critique of the patriarchy and the insidious nature of power.

This is due in no small part to the indelible characters Toews has given life to, bringing together—as in previous novels like 2014’s All My Puny Sorrows—tragedy and humor, rage and warmth. There is the fiery, scythe-wielding Salome Friesen, who frequently butts heads with the no-less-headstrong Loewen sisters Mejal and Mariche; weathered matriarchs Greta and Agata; mischievous teenage cousins Autje and Neitje; and Ona, the beatific, patient older sister to Salome, and ostensible protagonist. Dismissed as a dreamer, Ona asks the kinds of probing questions that often lead to the group’s most significant insights. (It’s a slyly thrilling moment when she proffers an impossible fourth course of action: that they ask the men to leave.) When the women fight, it is the fighting of sisters, of those who have known each other all their lives—expertly lunging for weaknesses while remaining fiercely loyal—which affords the novel much of its levity. Humor also arrives as interruptions in the loft, like the child with a cherry pit stuck in his nose, or Autje and Neitje pretending, multiple times, to kill themselves.

And then there is the boys’ schoolteacher, August, “an absurd flightless bird” who has been tasked with taking the minutes of the meeting, as the women cannot read or write. Anxiously tugging at his hair and raising his hand to speak, August is humbly dutiful to not just Ona, who he is hopelessly in love with, but all the women and girls. Through his warm eyes, Greta’s arthritic knuckles bulge “like the rings of a Tudor king”; Salome is “our warrior, our captain”; and Ona’s laughter is “the most exquisite sound in all of nature.”

The title’s blunt simplicity underscores the significance of women having the time and space to talk to each other outside of the presence of their oppressors. Groups of women speaking honestly and freely have long been dismissed as gossiping hens while also eyed with suspicion, a contradiction these brave women use to their advantage. “What are you bitches plotting?” a man demands late in the novel. “[T]here’s no plot,” is the reply. “[W]e’re only women talking.”

“There must be satisfaction gained in accurately naming the thing that torments you,” August thinks at one point. His story is bittersweet—heartbreaking in its own way. The “half-man” insults he shoulders reveal the damaging effects of toxic masculinity on both women and men; it turns out the Friesens and the Loewens are not the only ones fighting for their lives. As day one comes to a close, he likens the elder Friesen’s breathing to “a balloon, pinched at the end to prevent the air from escaping, then released so that the air escapes quickly and noisily.” It could describe the women themselves and their impassioned, immediate voices. In August, Toews has created a vessel worthy of carrying this story, proving it’s as powerful for others to listen, as it is for women to speak.