An evil legacy overshadows the complexities of Bully. Coward. Victim.: The Story Of Roy Cohn

The second recent documentary focused on Roy Cohn, Bully. Coward. Victim.: The Story Of Roy Cohn is as stuffed and jumbled as its title’s punctuation. Despite this, the film manages to inject some genuine personality into its Wiki reckoning of Cohn’s cursed résumé. The disbarred lawyer, fixer, and all-around political wheedler died in 1986, but his particular brand of self-assured, self-serving cruelty still haunts the current American consciousness. The adage that “there’s always a tweet” to point out President Donald Trump’s raging hypocrisy was foreshadowed by his mentor’s lifestyle.

Cohn was publicly anti-gay, summered in popular gay destination Provincetown, and died of AIDS; he was Jewish and pushed to make a specifically deadly example out of Jewish Communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. These self-loathing contradictions aren’t rare—outed homophobes became such a headline staple that it’s turned into a lazy trope—but they’ve rarely been so bold. The documentary’s title (taken from Cohn’s square on the AIDS Memorial Quilt) promises stark ideological juxtapositions and the epitaph epigraph doesn’t disappoint.

The film goes through Cohn’s body of work—from his days breaking court protocol as Senator Joseph McCarthy’s boy wonder to his ’70s defense of Trump’s racist rentals—with plenty of colorful asides from those that either knew him (cousins, friends) or helped the world know him (Angels In America’s Nathan Lane and Tony Kushner), finding pockets of intimacy as it weighs an obviously blackened heart. Director Ivy Meeropol, granddaughter of the Rosenbergs, uses her family connection to tether the fury of an otherwise wide-ranging, fist-shaking, grave-spitting affair.

A tangential follow-up to her 2004 documentary Heir To An Execution, Bully. Coward. Victim. allows Meeropol to revisit the Rosenberg case in a way that helps contextualize the long-term fallout of glory-seeking misanthropy and unflappable bullshit-mongering. The interviews with Meeropol’s father, Michael, are the most affecting portions of the film. They’re also the few segments that aren’t talking heads or archival footage/audio. The execution of the Rosenbergs dominated Michael’s life as trauma, while it acted as a heinous calling card for Cohn. Home movie footage—Michael telling Meeropol about her grandparents—a visit to Sing Sing, and Michael’s memory of coincidentally discovering Cohn’s square on the aforementioned quilt all drive home the sadistic intimacy between the families.

This closeness and personal insight don’t last, though the doc continues to be more conversational and anecdotal, with hard numbers and receipts only unearthed as an aside: This is Roy Cohn as remembered by friends and enemies, who often share the same assessment. Everyone agrees that Cohn was a bad man, but not everyone agrees what his story (or the film about it) should be. Journalist Peter Manso calls his old co-renter “a lawless madman,” while others (gossip columnist and Cohn enabler Cindy Adams, Cohn cohort Alan Dershowitz) remember his deadbeat lifestyle or confided crimes. “He never denied that the case was fixed,” the latter says of the Rosenberg trial. “He told me, ‘We framed guilty people.’”

But most of the film isn’t relitigating atomic spies. Meeropol’s three-way ping-ponging interests of Cohn’s legal escapades, his barely closeted social life, and his legacy as it lives on through Trump often bounce off the table and scatter around the room. Rarely intersecting, these qualities pop up eclectically before the film grows tired of them and, remembering the other points it wants to make, tosses them aside. Bully. Coward. Victim. is so caught up in regaling us with the full breadth of Cohn’s lifelong dickishness that it never finds a full picture of a man amidst his actions.

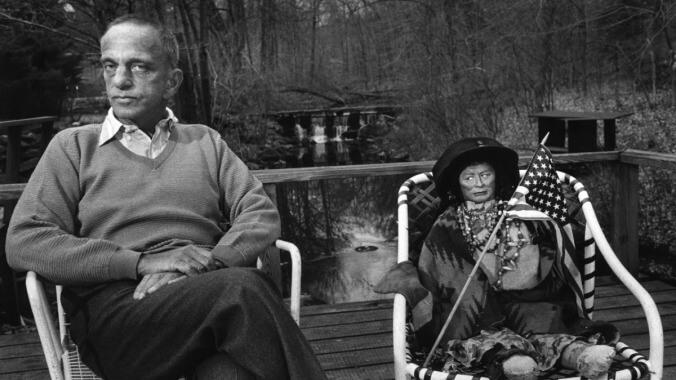

Cohn’s collective personal dissonance is visible in every frame containing his face, leather-tanned yet utterly devoid of warmth, but the closest the film gets to cracking that syrup-colored callous is when speaking to his old Provincetown landlady, who remembers how Cohn was almost never, ever alone. When Meeropol discards her star-studded lineup of interviewees, her visuals are more impactful than half the crusty war stories. Shots of a newspaper-strewn poolside chaise, stacks of nebulous bank deposits to a young lover, or upper-downer-inclusive restaurant place-setting offer up brief aesthetic snapshots of a life—making Cohn seem more real, and thus more truly sinister, than a dozen testimonials.

As the specter of Ethel Rosenberg haunted Cohn in Angels In America, the ghost of Cohn is plagued by the Rolodex he carefully cultivated. With everyone offering their own version of the man—including comparatively tepid clips of the play containing his most famous pop-cultural depiction (sorry, The X-Files)—colored by their own agendas and contemporary ties, the main takeaway about a defining force in modern American politics is that he was scum. If you didn’t know that before, everyone (including the soundtrack) informs you at every possible opportunity.

Sometimes that’s satisfying, even dolloped on as thick as the thin observation can be. Bully. Coward. Victim., taken as a history lesson, entertains in its scatterbrained way, but mostly fuels impotent rage. More disheartening, whenever the distracted film (although more interested in Cohn as a person than Where’s My Roy Cohn?) ties Cohn’s personality, actions, and ambitions to the current leader of the U.S., its chorus of hatred heralds the similarly united and angry responses found quoting every tweet spasming out of Trump’s fingers. Two imperfect studies of Roy Cohn only make understanding his hateful human heirloom even more daunting.