With Eastwood, one comes to accept the bum notes and imperfections because of his ability to powerfully articulate a theme. (This is probably the most obvious through-line between Eastwood’s filmmaking and his other great passion: jazz piano.) And there is a germ of something buried in The 15:17 To Paris, which dawdlingly follows real-life friends Spencer Stone, Alek Skarlatos, and Anthony Sadler from their grade school days in Sacramento, California, all the way to the fateful afternoon they boarded an express train to Paris. These are unexceptional guys, the film seems to say. Stone (the only one with any screen presence) struggles and flunks through Air Force training. The only substantial thing we see of Skarlatos’ National Guard deployment in Afghanistan is a humiliating incident involving a lost backpack. (Sadler, the one who didn’t join the military, gets less screen time in the first half of the film.) Loosely, the film sketches an idea of heroism: It’s not about being the best, but doing the right thing when it counts. This isn’t a bad moral, but the more cynical might also call it a mea culpa.

Docufiction movies that cast ordinary people in reenactments of their own unlikely life events have an interesting history. There is, for instance, Close-Up, Abbas Kiarostami’s layered masterpiece about an Iranian film buff who conned a family by pretending to be a famous director, in which all the parties involved play themselves. Or the most morbid example of the subgenre, a bizarre Communist-era Romanian propaganda film called Reconstruction, in which a gang of bank robbers recreated their purported crimes and capture before being executed. But the most relevant to Eastwood is probably To Hell And Back, the mid-1950s Technicolor blockbuster that starred Audie Murphy, one of the most decorated American soldiers of World War II, as himself. But Murphy was by then well into a solid acting career. He even starred in two Westerns directed by Eastwood’s mentor, Don Siegel.

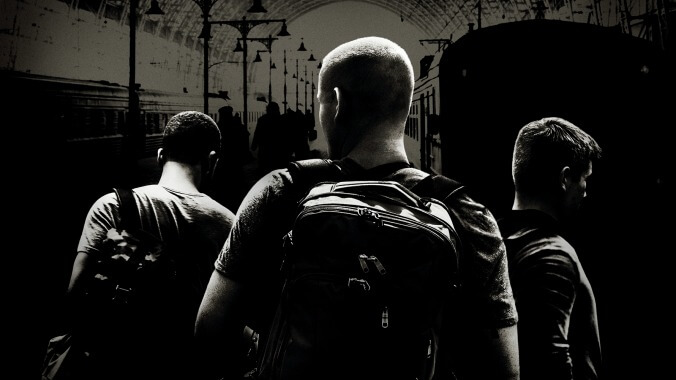

On paper, 15:17’s potential seems obvious, touching on Eastwood’s fascination with the backstories of life-defining media events (Flags Of Our Fathers, Sully) and his late-career interest in distancing effects. The gimmicky casting creates tension in the climax, with real people reenacting a horrific episode as they grapple with an actor playing someone who tried to kill them. But the rest is mostly tedious suckage, stiff as an octogenarian’s knees: glorified home movies of Stone and Sadler touristing around European capitals and museums; classroom scenes with child actors who appear to have been given zero direction; clumsy digs at snobs on both sides of the Atlantic. Performances in Eastwood films are usually uneven, but here his hands-off directing style shows no mercy; the only professional actors who emerge unscathed are the handful of comedy veterans (including Tony Hale and Thomas Lennon) eccentrically cast as teachers and school administrators at the uppity Christian school where our three heroes first meet as boys.

But as the old Miles Davis quote about jazz goes, it’s all about the notes you don’t play. In the case of 15:17, that includes the macabre aftermath of the attack: Returning home as an international hero, Stone was stabbed and almost killed by a stranger outside of a Sacramento nightclub. There’s an interesting story there.