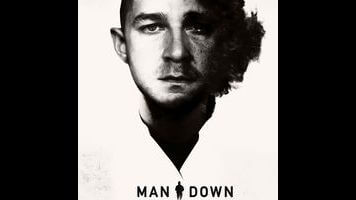

An overqualified Shia LaBeouf can’t rescue Man Down

The low-wattage, high-concept psychological drama Man Down is too misbegotten to be rescued by Shia LaBeouf’s Method lead performance; in fact, the most interesting thing about it is his masochistic commitment to the film. Directed and co-written by the once promising Dito Montiel (Fighting), the movie sloppily juggles three narrative lines: one that follows a Marine named Gabriel Drummer (LaBeouf) from boot camp to Afghanistan and back; another set at an afternoon session with a military therapist (Gary Oldman); and a third that takes place in a post-apocalyptic future, where Drummer and his best friend, Devin (Jai Courtney), wander an America that has been overrun by Islamist militants following a chemical attack that killed most of the population. There are a couple of easy-to-guess twists to this, but all they do is turn a bad movie into, well, a different kind of bad movie.

Yet it deserves to be said that LaBeouf’s performance is no wrongheaded stunt, but a work of interiorized and believably instinctual acting that could be the highlight of any film. It’s a quiet performance, but doesn’t feel measured or timed. It breathes in the character’s personal space, whether he’s a clean-cut Marine trying to make small talk or a bearded survivor scavenging for supplies in the ruins. But Montiel, who first cast LaBeouf as his teenage alter ego in the autobiographical A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints (with Robert Downey Jr. as the grown-up version), drowns this fragile characterization in tripe. If anyone needed proof that an actor’s integrity and their taste in material are two different things, then Man Down is it. The film is a study in unwarranted effort, as there’s no way that this tone-deaf, quasi-coherent allegory about the treatment of America’s combat veterans could have turned out as anything but turgid.

Man Down has a moral about the trauma of war, which it imparts through a ham-fisted third-act reveal, like some rejected spec script for a revival of The Twilight Zone. Calling it manipulative isn’t accurate, since that implies a degree of success. The Red Dawn-by-way-of-zombie-movies future timeline (which seems to interest Montiel the least) and the Afghanistan sequences are realized with the finesse and gravity of a fan film. The scenes of Drummer at home with his wife (a disposable Kate Mara) and moppet son are flimsy and underwritten, but are given small specks of life by LaBeouf’s improvised chatter. (At least one assumes that a non sequitur like “What do you know about dog hats?” is improvised.) There is a soundtrack of sappy original ballads, which could really be any blandly generated set of songs.

Despite cinematographer Shelly Johnson’s attempts at imitating the hazed lighting style of Janusz Kaminski, the movie doesn’t look convincingly like anything. It exists entirely to hide its sophomoric secrets—the nature of the “incident” discussed in Drummer’s therapy session, the question of how the future America came to be, the relationship between Drummer and Devin—and then present them as profound insights. When Man Down played film festivals over a year ago, it was often met with jeers and walkouts; the only apparent improvement that has been made since then is the fact that most of the movie is no longer color-graded in a sewage-runoff palette of watery fecal browns. Some blue has been added.