André Téchiné, who was once a film critic, reached a turning point with his 1981 masterpiece Hôtel Des Amériques, a psychodrama of doomed romance in early middle age, set in the French resort town of Biarritz. In his telling, it was the film where he finally broke his addiction to movie references and pastiche. The truth is that he didn’t quit cold turkey (Hôtel Des Amériques is almost operatic in spots), but he began a process through which he would refine the concerns of his generation of post-French New Wave filmmakers into a form of classicism. It’s easy to make Téchiné’s movies sound boring or stodgy, which is probably why they’ve never had the following they deserve in America. These are dramas in which the constancy of seasons, landscapes, and chapters gives definition to messy and unpredictable consequences, conveying the flaws of human nature in deft strokes and incremental detail.

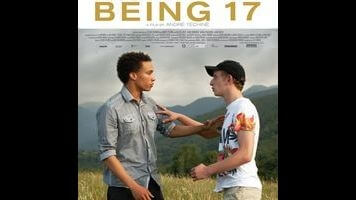

Being 17, the queer coming-of-age drama that Téchiné co-wrote with Céline Sciamma (Girlhood, Tomboy), is another act of self-purification. For better or worse, he’s never made a movie in which the dialogue mattered so little, even though it’s just as talky as his other films. Téchiné drops his signature smooth camerawork in favor of a rocky, semi-spontaneous handheld camera, painting the relationship between Damien (Kacey Mottet Klein) and Tom (Corentin Fila), classmates in a small town at the foot of the central Pyrénées, through close-ups, violence, and movement. It’s the gradual transformation of antagonism into fascination and then friendship and evasive attraction—these two teenagers wrestling with their feelings by attacking each other, in that strange way that an object of desire can be projected with self-resentment.

Téchiné’s portrayals of class, self-discovery, erotic fascination, provincial life, and distant war—favorite subjects, all accounted for here—are often delicate, complicated by ensemble casts. But here, they are reduced to two characters, with occasional emotional input from a third: Marianne (Sandrine Kiberlain), Damien’s loving and lonely mother, a physician who arm-wrestles her son at the dinner table for fun. Téchiné makes his movies like novels, and over the nearly two-hour running time (somewhat overextended), his treatment of the broader social backdrop is just as physical as his conception of the characters: arduous commutes to school; boxing practice; basketball; the toil of farm work; Skype calls from Damien’s father, a soldier deployed overseas. It’s become a tired cliché for critics to observe that a filmmaker’s work is “about bodies” (what isn’t?), but Téchiné’s movies are, on levels within levels. They’re fascinated with the beauty of youth but also with ethnic tension, sexuality, and basically any situation where a body is assigned a value.

None of this is new stuff for Téchiné, who explored the same themes (and even some similar plot points) more expansively in the autobiographical Wild Reeds, one of the great coming-of-age films of the 1990s. Being 17 could be called a ruggedized Téchiné, its physicality inspired by the mountain landscape that is meant to be hiked, not strolled. The forces of nature lend their own poetry in the form of rain, snow, and fog, while the narrative is broken up into trimesters that correspond to both the French school year (and, by extension, the changing seasons) and to a secondary character’s pregnancy. There’s a great moment where Tom and Damien first bond: Hiding from a rainstorm at the entrance to a cavern, they are lit in silhouette as they pass a rolled cigarette back and forth with their wet hands. There is nothing that the movie can express in dialogue that can match these brief nonverbal exchanges. Téchiné has made one of his simplest and most elemental films, which is both Being 17’s most arresting feature and its weakness.