Andrea Arnold's pop-filled movies still find love in hopeless places

Music plays a crucial role in the movies of Andrea Arnold. With Bird, her song choices soften and embrace cheesiness.

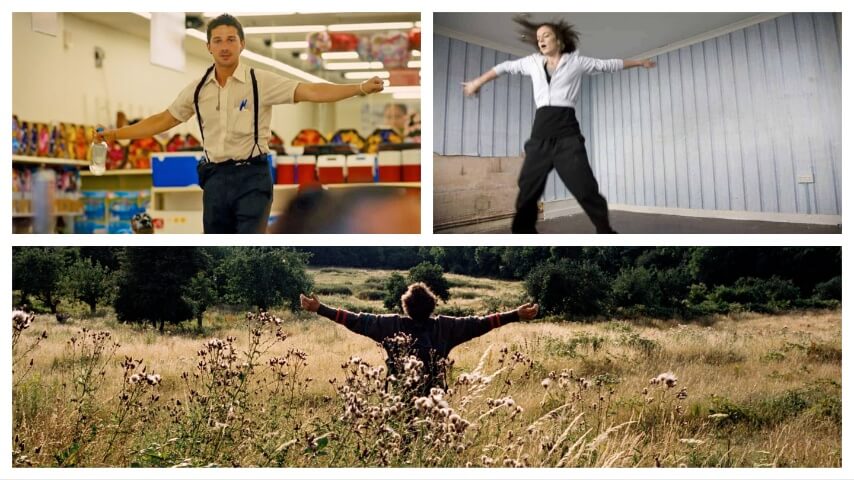

Photo (clockwise from top left): A24, IFC Films, MUBI

In a pub somewhere in Kent, England, a heavily tattooed man serenades his new wife with a cover of Blur’s “The Universal.” As he croons along to the lyrics “it really, really, really could happen,” his young daughter embraces a human-bird hybrid in a quiet corner of the room. The creature’s wings cocoon around her, veiling them from the prying eyes of the wedding party. Their drunken singing is muffled by his feathers, elevating the sound of this odd pair breathing in sync.

This touching scene closes Andrea Arnold’s Bird, a fantastical fairy tale about 12-year-old Bailey (Nykiya Adams) who lives with her father Bug (Barry Keoghan) in a squat in Kent. The choice of song may come across as odd, but it captures Andrea Arnold’s filmmaking style perfectly. The director has garnered a reputation for idiosyncratic music choices, and recently admitted that music is so important to her process that she carries around a speaker on set to play music in between takes. It’s a quirk that sets her work apart from her peers—rather than using songs as non-diegetic needledrops, Arnold weaves the music into her stories, tying each track to her characters and their experiences. Like a Greek chorus inflecting a tragedy with narrative insight, Arnold’s soundtracks are shaped by the music her protagonists listen to themselves, clueing the audience into their state of mind while simultaneously scoring her films. She never shies away from using contemporary music in the process: Fish Tank is populated by the sound of Cassie, Ja Rule, and Ashanti; American Honey by Rihanna and Rae Sremmurd. Modern music is to Arnold as much a tool in storytelling as anything else, and it often becomes the primary method through which she translates her characters to her audience.

With the exception of her feature debut Red Road and her 2011 adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Arnold’s films tend to follow a similar through-line. Her filmography is dominated by kitchen-sink dramas about the British working class or gritty coming-of-age stories, each of which utilize sound and music to help drive the narratives forward. She first set this trend with Fish Tank, where 15-year-old Mia (Katie Jarvis) escapes the mundanity of her suffocating East London council estate by choreographing dance routines while picturing herself as a dancer in a hip-hop music video. In aligning herself musically with a genre that is a far cry from her British white working class reality, Mia conveys an unspoken desire for a life beyond the limitations of the poverty-stricken world around her, finding solidarity in the themes and lyrics of her songs of choice.

As Mia navigates her growing attraction towards her mother’s boyfriend Connor (Michael Fassbender), music plays a crucial role in narrating her story. At the start of the film, Steel Pulse’s “Your House” echoes through Mia’s home, the lyric “I wanna live in your house,” booming in the background as she and her mother argue over her anti-social behavior. Later, Connor plays Bobby Womack’s cover of “California Dreamin’” in the car as Mia watches him, starry-eyed. When she finally breaks free of his hold, she leaves behind the Bobby Womack CD she stole from him, abandoning her fantasies of living out a California dream and instead returning home to dance with her mother and sister one last time. The song? Nas’ “Life’s a Bitch,” a hilariously on-the-nose summation of Mia’s life up to this point.

Bird tells a similar story of a young girl seeking genuine connection in the face of a tumultuous home life, but this time Arnold leaves behind the glitzy hedonism of American hip-hop and reaches for the kind of music you’d more expect to find in a film about the British working class. Punctuating this odd, sweet film are the ambient sounds of Blur, The Verve, and Fontaines D.C. (guitarist Carlos O’Connell even makes an appearance in the film) alongside an original score composed by British musician Burial. Each song is chosen to reflect the turbulence of Bailey’s life and her relationship with her father, which dances to a volatile rhythm. The Fontaines tracks particularly feel like they could’ve been written with this film in mind; the chorus of “A Hero’s Death” assures us that “life ain’t always empty” in what sounds like a direct message to Bailey herself, and the repeated refrain of “I’m about to make a lot of money” in “Too Real” could’ve easily been crafted by Bug in the midst of one of his ludicrous get-rich-quick schemes.

Between these songs, Andrea Arnold even finds the time to take a few swipes at the popular songs of today—Bailey is horrified at the prospect of her father’s new fiancée polluting their lives with the music of Harry Styles, and Bug insults Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s “Murder on the Dancefloor,” a nudge and a wink to audiences that are perhaps still recovering from the torturous final moments in Saltburn.

In keeping with the chaotic pulse of its soundtrack, Bird embraces whimsy with incongruous realism, undoubtedly Arnold’s most fantastical film to date. Where her previous films approach teenage coming-of-age narratives in a decidedly no-nonsense manner, Bird dives headfirst into the strangeness of this transformative period by using the figure of a human-bird hybrid to concoct a genuinely heartwarming story about the power of human connection. With three younger siblings and a mother who has a penchant for loutish boyfriends, Bailey assumes the role of caretaker at an extremely young age, forcing herself to grow up ahead of her time. Away from the ruckus of her home, her life is transformed by an encounter with a strange yet gentle man who goes by the name Bird (Franz Rogowski). Bird befriends Bailey and imbues her life with a new sense of curiosity as she navigates the ebbs and flows of pre-teenhood. In any other circumstance, Bailey’s connection with a stranger she met in a field would be cause for alarm, but through Arnold’s lens, this relationship is rendered pure. Bird is Bailey’s guardian angel, the figure sent to finally look after her after a childhood spent fending for herself. He offers Bailey an escape from the ramshackle squat that she lives in with her family, and though unwilling to outwardly express her gratitude, she accepts this escape with open arms.

These sincere moments are balanced by the film’s more absurd plot points—Bug’s attempt at honest work comes in the form of a harebrained scheme involving a “drug toad” and hallucinogenic slime that is only produced when the toad hears “sincere music.” What follows is an utterly ridiculous scene where Bug serenades the amphibian with a rendition of Coldplay’s “Yellow” alongside a room full of quasi-adults, all drunk, or high, or both. As cheesy as the song is, there’s surprising depth behind Arnold’s choice to include this particular Coldplay song in this film. Just as Steel Pulse translates Mia’s desire for a stable home in Fish Tank, the lyrics to “Yellow” speak to Bailey’s relationship with her two father figures. Irresponsible though he may be, Bug refuses to relinquish his role as father and when he’s holding onto his son—begging him not to run away and reminding him that he has a home, while Bailey watches this outpouring of love—there is the sense that maybe he would bleed himself dry for his kids.

Bird’s connection to the song is a little more literal—like the lyrics, his skin and bones quite literally fade away into a majestic animal that protects Bailey from her mother’s abusive boyfriend Skate (James Nelson-Joyce). As Bailey lies on the floor, curled up in the fetal position to avoid Skate’s blows and looking more like a child than she has at any other point in the film, Bird appears like a knight in feathered armor. He transforms as Bailey watches transfixed. His skin tears away and tremendous wings sprout from his back, engulfing Bailey in their shadow and sheltering her from Skate’s violence. Here, Arnold forgoes music and score almost entirely, instead forcing us to sit with the oppressive sound of Bird’s ferocious cawing, his wings flapping and Skate screaming in agony as Bailey and her family are saved from the brute. In this sequence, Bird—who found Bailey in his search for family—becomes the fearsome predator protecting his young.

Bug’s displays of love aren’t quite as heroic as Bird’s, but him serenading his wife with his children sitting in the front row still makes for an embarrassingly endearing watch. You’d be forgiven for flinching upon hearing Keoghan sing off-key, but the tenderness of the scene cannot go unnoticed. As Bug sings about letting go of the bad days, he takes his first steps towards a new life with his family; his wedding is the perfect site for the beginning of this new chapter. Where both Bailey and Bug had initially scoffed at the mention of cheesy music, they now dance freely to Rednex’s “Cotton Eye Joe,” caving to the unbridled joy of dancing to such an upbeat song with friends. This newfound freedom mirrors Arnold’s own journey, from the discordant use of hip-hop to deflect from the earnestness of her stories to an acceptance of all that is sincere. When Bird returns to bid farewell to Bailey, unfurling his wings to wrap around her as he assures her that she will be okay, it is a moment of gentle catharsis captured amongst the chaos of this boisterous celebration. The wedding party continues to dance around them completely unaware of the bittersweet parting taking place, and as the sound of drunken karaoke filters through once more, Bailey finally lets go.

Andrea Arnold has developed a unique musical language that has evolved alongside her career. It was once the larger-than-life sounds of E-40 and Eric B. & Rakim that were used to convey the complexities of her tenacious characters, but in Bird, she achieves the impossible by choosing one of the most bland songs to ever exist (sorry, Chris Martin) and molding her characters around its lyrics, using the pop track as a blank canvas upon which a moving story about family and human connection can be painted. By changing her tune from the bouncing sounds of American hip-hop to the more subdued tones of English and Irish musicians, Arnold softens her approach to coming-of-age stories and embraces sincerity in all its insufferable glory.