Andrew Bird knows better than anyone this is his Finest Work Yet

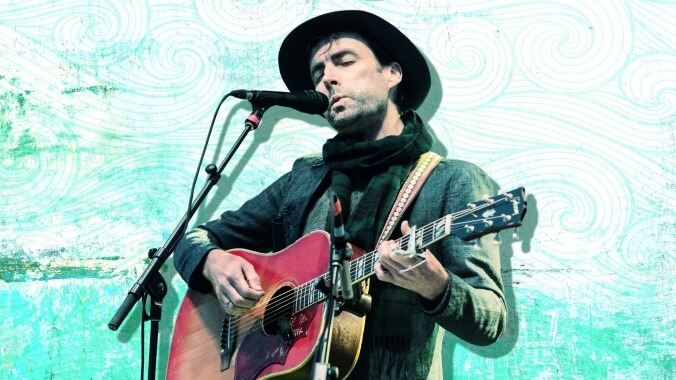

Image: Photo: Jim Bennett/WireImageGraphic: Allison Corr

Ambiguity, like virtuosic whistling and erudite lyrics, is a hallmark of Andrew Bird’s music, but it’s seemingly absent from the title of his latest album, which the multi-instrumentalist and singer-songwriter has dubbed My Finest Work Yet. The other superlative in the discussion around the 10-track album, which is out Friday, is that it’s Bird’s most political or topical work to date, thanks in part to the Lake Forest native being forthcoming about the real-life events that informed tracks like “Bloodless.” But My Finest Work Yet travels further back than the 2016 election, diving deep into our country’s enmities and conflicts while never losing sight of a way out.

Ahead of the album’s release, The A.V. Club spoke with Bird over the phone (with a labor demonstration going on right outside our doors, no less) about his songwriting inspirations and hang-ups, and how well My Finest Work Yet backs up its own assertion.

The A.V. Club: In addition to raising the question of whether this is your finest work yet, the conversation around the album has also been about it being maybe your most political work to date. My Finest Work Yet certainly explores a lot of divisions in this country—it’s not just like, “the citizenry against an authoritarian government.” You’re also talking about overconsumption and echo chambers.

Andrew Bird: Well, I like to keep enough room in there that it can be taken from a personal conflict between two people, or on an international scale. It depends on what you’re thinking about as you’re listening to it. That’s the trick with writing songs that are about what’s going on: If you mention dates and names, you can sink the song right away. It won’t go anywhere. You’re riding this line between metaphor and reality, and how topical can you be—you need to keep the song above the noise of the 24-hour news feed.

There are all these songs that have made it across airways that are dealing with anything that’s going on now—these are troubled times, you know? And I think what better medium than songwriting to go in deep and figure out what’s really going on and maybe offer suggestions of how to get out of it. So a lot of the songs, from “Archipelago,” “Fallorun,” to “Bloodless,” they’re dealing with this deal that’s been made that we’re somewhat unwittingly being played by these people that are profiting through algorithms and whatnot on this division, and just amplifying it. And the more they amplify it, the more they seem to benefit from it. It’s just taking things that have always been there, and exploiting them, and making them worse for profit. It has to do with a certain aspect of human nature that’s been around for eons. But it’s just that attraction one has to their enemies—what space, what void in us is being filled by our adversaries? And how that gets our horns locked and we can’t pull them out. And it’s that sort of intimacy, that need that’s being filled by your adversary. What would happen if you just walked away? They’d probably really miss you, you know?

AVC: What is it that they’d be missing out on if you—if we—kind of just withdraw from the argument or unplug from the news feed? Would it be the attention or source of tension?

AB: In the case of our nation’s leader, it’s everything—and we’re playing right into it. It’s like, I keep thinking of that old ’80s sci-fi horror trope of a blob that feeds on our fear and growing stronger, and the best thing you can do to shut it down is to turn away or not be afraid. But I think we also have to look in ourselves, too, and not just focus all our ire on one person but look at how we helped create this situation, all of us. Not every song is dealing with that, though, and I don’t think saying it’s a political record, per se, is entirely accurate. But I’d say on eight of the 10 songs, that’s where I’m coming from, yeah. But I don’t think the music comes off as dark or hopeless.

AVC: Yeah, it’s quite the opposite—the overall sound is almost boisterous at times, especially on a song like “Fallorun.” That chorus is so great to sing along with, even as you’re calling some folks out. Who is that song about?

AB: Well, the first lines sounds like they could be about a relationship: “You could have been together but you couldn’t stand the weather.” So it’s this kind of geographical solution, like, “I’m out of here. I just can’t handle this atmosphere.” That’s something I heard a lot after the election, that, “Yeah, I’m moving to New Zealand or Sweden.” [Laughs.] And that’s the most cowardly thing you could say at this moment, to say you’re concerned that remaining here is “harshing” your mental state. That makes you—you’re part of the problem, man. What are you doing? And of course, they don’t go anywhere. That was a cool thing to say after the election, and I was like, “What are you thinking?”

That’s something I heard a lot after the election, that, “Yeah, I’m moving to New Zealand or Sweden.” And that’s the most cowardly thing you could say at this moment.

AVC: I’ve been thinking about what options are being presented in that title: “Fallorun,” and what it means to “fall” or “run.”

AB: Yeah, I kind of stumbled on that word, “Fallorun.” I kind of ran the two together. I was going through, like, five different possible choruses that were all way too heavy-handed, I think. “Fall of throne.” And then my wife thought I was saying “fall or run,” instead of “Fallorun.” And I thought, “That’s actually better than ‘fall of throne.’” And so it is talking about that fight-or-flight instinct. And it’s just sort of addressing that, “What is patriotism?” And the verse is, beyond those first couple lines, “What if Trump were not human, he was just an algorithm that takes all our worst impulses as people and amplifies them and exploits them, turns them on us?” That’s effectively what we’re dealing with. It’s just almost a reflection of ourselves in a way.

The A.V. Club: “Manifest” is the latest song to be released off the album. You touch on chasms here, too, but was there additional inspiration for the song?

AB: Yeah, I guess I was thinking about fossil fuels—just that term is kind of interesting in how it points out that what we pull out of the ground and put into a combustible engine is the result of millions of years of plants and animals dying and being compressed underground and being fossilized. But I also wanted to look at the afterlife for those organic things. There’s still energy contained in that organic matter, and that’s what we’re doing, is spending the last bit of energy of that life form. And from there it becomes vapor, so it’s almost like the ghost of that thing. There’s a certain poetry to all that, as frightening as it is. So that’s mostly what it’s about.

The first line is like, “Coming to the edge of the widest canyon.” I was imagining the Spanish explorers coming to the edge of the Grand Canyon, and in that moment thinking, “Whoa, we just got to the end of it all.” That’s how the song kind of started, but the chorus is talking about the tendrils, the fracking, these things going deep into the ground to find every little bit of fossilized fuel. The video that’s out at the moment is just us in the studio, but there’s an official video coming out in, like, a week and a half that’s an animated thing that kind of takes this—do you remember Carl Sagan’s Cosmos? [It] had a famous animation of the evolution of creatures from the sea to land to modern man, and we’re kind of riffing on that idea for it. I just got the final video today. It’s great.

AVC: “Cracking Codes” feels like one of the “bread and roses” moments on the albums; it’s more personal, and a bit narrower in focus.

AB: Yeah, it sounds more like a love song than anything else on the record. The chorus is about either telling the truth, or just being able to tell if someone is being true—that search for truth relates to everything else on the album. And through it I’m just talking about how even without words two people can, through body language or just even atmosphere that one creates with energy, that you can just tell if someone is really who they say they are. ’Cause it’s quite straightforward. I wrote that song very quickly, and so it hangs together better than anything I’ve written in a long time.

AVC: The album title is more playful than anything, but if you made the statement in earnest, how would you come to realize this is your finest work yet? You have an extensive discography, which means you have a lot to compare. Is it kind of just like a gut feeling in the middle of the night after finishing recording, or is there something more measurable?

AB: I’d say having such an extensive discography makes me saying something like that about myself more okay, you know what I mean? It started off as just a joke with myself or with a few other people that I was sharing the early demos with. Those working titles tended to be more honest. I went through 100 other heavy-handed poetic titles for these 10 songs.

AVC: Like what?

AB: I really liked “Inside Problems,” but that didn’t really make sense for these songs. I was really trying to convey this idea of horns being locked, of a struggle of two wrestlers just starting to make out or something. Two people or sides, just so close and so intimate, yet locked in the struggle. And I couldn’t figure out a way to do that without it being just too much. So I gave up on trying to encapsulate the whole record with a few words, and that process just seemed kind of silly on record No. 14 anyway. So I just went with this somewhat tongue-in-cheek statement.

But that being said, these songs do feel different to me. There was an urgency in the writing of them that felt different, like I had a purpose even though I was still kind of doing what I was always do, which is pay attention to what’s around me and process it. It’s not all that deliberate, but it was just a result of being alive in these times. Nonetheless, there was a little more just, increasingly from record to record, a desire to communicate specific things. The trick is, how explicit can you be with that without being—it’s just the line between explicitness and ambiguity. It’s all a dance.

AVC: You highlight that idea of intimacy between sets of opponents on “Archipelago,” which has that refrain, that we’re not on some remote island or even chain of islands. We don’t see ourselves as being very close to the people that we think are against us; it kind of puts a new spin on the idea of “we’re all in this together.”

AB: Right. You could describe it as a great divide, but I see it as a form of intimacy. I can’t quite explain why, but I think it’s because that person is feeling something enough that should probably be filled with something that really helps you instead of drags you down.

AVC: The songs make up this kind of path to war, from trying to avoid it on “Fallorun” to spouting propaganda on “Proxy War,” and then there’s a call to “Don The Struggle.” Is the album closer, “Bellevue Bridge Club,” intended to bring an end to the conflict?

AB: That song, I’ve been writing for a long time, five or six years. It went through so many versions. As opposed to “Cracking Codes,” which took a half an hour, this one took years. And eventually I scrapped everything in the song except this line, “We’ll be playing bridge in the psych ward with Barbara, Jean, and Sue.” I had the hardest time working backwards and figuring out what makes that line make sense. All I knew is that that was the best line in the song. The original idea was someone coming home from the Great War and seeing horrible things and just wanting to have a boring life, or in this case, suffering, or recovering from shell shock in the psych ward just playing bridge, and wanting to live in a small town—I always thought of that as being this really interesting thing about World War I or World War II, you know, coming home. And so it took me forever to set up that final line to the song.

Something that’s been happening on the last couple records is that I embrace the second voice that enters in my head as I’m writing a song, the one that’s a bit critical of the song. I think it’s a refreshing thing, and usually people don’t choose to put their own self-doubt in the song, they usually try to block that voice out. But I kind of like to embrace ’cause it gives us a break from the first-person narrative that you’re listening to through most of the record. And so that’s where that line comes from, “There you go again, finding brilliant ways to make things harder. Are we smarter alone or in this endless Stockholm syndrome?”

I do choose to end the record with maybe not the most healthy profile of a relationship. [Laughs.] But it’s a relationship, nonetheless. And then after this lifetime of—I was just thinking a lot about what an appetite people have for drama and conflict, and after this lifetime of fighting, there’s this: living out the final years in the psych ward playing bridge. Just a pretty picture.

Am I worried people are gonna be put off? If they are, I don’t know what I can do for them because it’s just a result of being alive in these times. It would be conspicuous to not talk about it.

AVC: You mentioned relationships. What about the relationship with your fans, the people who have been listening to your music from the beginning or just a long time? Do you think there are some people who are going to be put off by the topicality of the album?

AB: I don’t know. The only feedback I’ve gotten so far from people who don’t share my views is like, “I dig your music even though I don’t agree with you,” or something like that. Generally, it hasn’t inspired salon vitriol. But that’s the goal if you want to get beyond the choir, is to make the music so damn appealing and make the issues I’m talking about so big-picture that you’d have a hard time taking issue with it, honestly. I’m sure plenty of people will, but really, I’m just trying to step back far enough from the whole conflict that, I mean, who can really argue with what I’m saying?

Am I worried people are gonna be put off? If they are, I don’t know what I can do for them because it’s just a result of being alive in these times. It would be conspicuous to not talk about it. And I’ve never been one to really write about girls and partying anyway, so no one should be too surprised.