Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken is an unintentionally campy POW biopic

There’s some stark poetry in the opening scenes of Angelina Jolie’s befuddling World War II biopic, suggesting that the actress-turned-director is attempting to unearth her inner Ida Lupino. With barely any introduction, Jolie drops viewers onto an American bombardier flying a mission over the coastal waters of Japan. A beautifully visualized aerial battle ensues (what else do you hire cinematographer Roger Deakins for if not pretty pictures?), during which attention is drawn, among all the strangely model-attractive soldiers, to Louis Zamperini (Jack O’Connell). What makes him so special? Cue flashback.

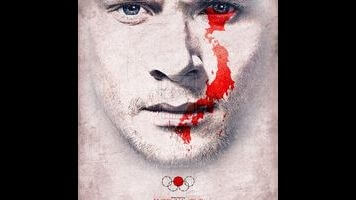

Those who have read Laura Hillenbrand’s bestselling 2010 non-fiction book Unbroken: A World War II Story Of Survival, Resilience, And Redemption on which the movie is based (the script was worked on by the curious quartet of Joel and Ethan Coen, Richard LaGravenese, and William Nicholson) will know Zamperini’s history. This son of Italian immigrants was a frequent target of bullies in his adolescence and found an outlet on the school track team. He was a natural runner, and became one of the youngest-ever Americans to qualify for the Olympics in the sport. He competed in Germany in 1936 and made a strong showing. An awestruck Hitler is even reported to have requested an audience with the young man, though the film doesn’t dramatize this particular event, nor does it bother with the all-American Zamperini’s later years when he found God and embarked on what sounds like a stunningly compassionate journey of forgiveness.

What it does show, primarily and endlessly, are brutal scenes from Zamperini’s WWII military career, during which, in Jolie’s telling, he becomes a huddled-masses messiah. During a bombardier mission, Zamperini and his crew crash-landed in the middle of the ocean. He survived 47 days at sea—subsisting on a diet of raw fish and albatross while avoiding constantly circling sharks—only to be captured by the Japanese army and interned in several prisoner-of-war camps. It was during this period that he was tortured, with great frequency, by a vicious prison guard named Mutsuhiro “The Bird” Watanabe (played as a fey closet case by Japanese pop star Miyavi). And it’s these penitentiary sequences—very Bridge On The River Kwai, with mincing sadomasochistic overtones—that Jolie wants the audience to remember.

There’s a dissertation to be written on Unbroken’s campy fascination with supple male flesh and its mortification. Every one of the prisoners is movie-star beautiful, primped to the gills whether caked in dirt or wasting away from starvation. (When inmate Garrett Hedlund displays a hand with fingernails ripped away, it’s as if he’s modeling the latest in Paris runway fashion.) O’Connell’s Zamperini, meanwhile, is the martyr who takes the majority of the body blows for and—in one uncomfortably protracted scene—from his countrymen. His master-servant rapport with “The Bird,” who belittles him with insults and beats him with a bamboo stick, is especially strange, coming off like a sanitized, PG-13 riff on Liliana Cavani’s infamous ode to wartime BDSM The Night Porter. Moral and spiritual triumph lie at the end of this hellish gauntlet, but though Jolie is shooting for Christ-like passion and redemption, she only ends up slathering one man’s very real, very morbid struggles in the usual reductive “greatest generation” sentiment.