Animal House was tame compared to Oxford’s class of 1355

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,016,226-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: St. Scholastica Day Riot

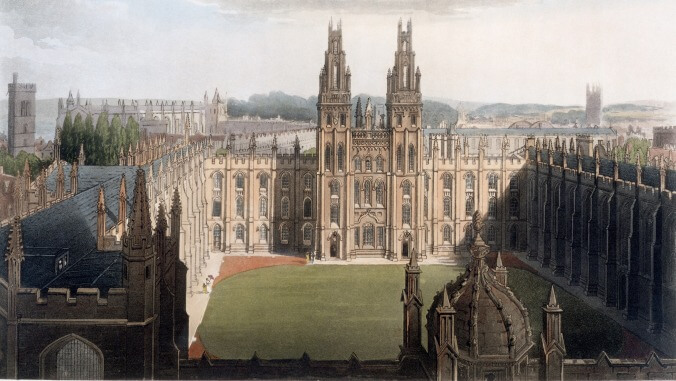

What it’s about: If you think today’s hard-partying college students are out of control, they’ve got nothing on Oxford University’s Class of 1355. When two students complained about the wine in a local tavern, the argument with the bartender came to blows, which turned into a bar brawl, which turned into a citywide riot that left nearly 100 people dead.

Biggest controversy: Neither patrons nor barkeep were ordinary Oxfordians. The wine critics are believed to have been Walter de Spryngeheuse and Roger de Chesterfield, two clergymen studying at the University (the former had been a rector, no word on the latter). The bartender was John de Croydon, who in various accounts was either the tavern’s vintner or the landlord, but in either case, the tavern itself was owned by John de Bereford, the mayor of Oxford. Their respective positions meant that when violence erupted, pre-existing tensions between the school, the town, and the clergy were very quickly enflamed.

Strangest fact: The Scholastica riots were the largest battle in an ongoing conflict. While every school has its “town vs. gown” rivalry, most don’t have the body count medieval Oxford did. As far back as 1209, two Oxford scholars were lynched after being suspects in the death of a local woman. Oxford was so shaken, a segment of the university community left town entirely and founded Cambridge University that same year. Between 1297 and 1322, 12 of the town’s 29 murder cases involved students. There were riots on campus in 1252, 1267, 1273, 1314, and one in 1333 that apparently carried over to the following year. In the 1314 riot (which involved students from north vs. south, leaving the townies out of it), 39 students “were known to have committed murder or manslaughter,” although only seven were arrested—the rest sought sanctuary in the church or escaped.

Into the already-tense town of Oxford then strode the Black Plague, which in 1349 killed a quarter of the student body and a significant part of the town, crippling the local economy and deepening the tension between students and townies. The community was still recovering in 1355 when the Scholastica riots happened.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: The town almost certainly made things worse by antagonizing the conflict. The initial bar fight escalated from de Chesterfield throwing his drink in de Croydon’s face, then throwing his wooden tankard at his head, to gangs armed with cudgels, staves, and bows. At one point, arrows were fired at the university chancellor—but by night’s end, there were no serious injuries.

That status would unfortunately change the next day. While the Chancellor and town magistrate issued proclamations that no one should cause any further disturbance, the town bailiffs were urging townies to arm themselves, and actually paying people from the countryside to come to town and help in the fight. A mob of 80 armed townsfolk surrounded some students in a church, killing at least one. Students had to bar the town gates to stop more armed men from entering the fray. By evening, the townies had as many as 2,000 reinforcements from the surrounding countryside. The crowd of outsiders waved a black banner and cried, “Havac! Havac! Smyt fast, give gode knocks!” (They even spoke in Olde-English spelling back then.) The mob broke into inns and hostels, killing or wounding any student they found (while helping themselves to food and drink). The students’ bodies were dumped into gutters, dunghills, or cesspits, or thrown into the Thames. Some reports claim that a few religious scholars were scalped (possibly mocking tonsures, which were still in fashion at the time). By the third day, the violence subsided, but not before most of the student body had fled and most of the town had burned down.

Thing we were happiest to learn: His majesty himself stepped in to end the madness. King Edward III happened to be staying eight miles away in Woodstock when the riots broke out. During the second day of rioting, he issued a royal proclamation “that no man should injure the scholars,” which was widely ignored. He summoned the university elders (who were fleeing Oxford either way), and very much came down on their side. After sending judges to the town to determine what had happened, the king pardoned the scholars, fined the town 500 marks (not to be confused with the Deutschmark, the long-defunct English mark was worth 160 pence), and imprisoned the mayor and bailiffs.

A few months later, Edward issued a royal charter reinforcing the university’s rights. The school’s chancellor now had broad-ranging powers, from taxing bread and drink sold in the town, to standardizing weights and measures. Any legal dispute that involved a student would be settled by the school, not the town. Every year on St. Scholastica’s Day, successive mayors and bailiffs would attend a mass at St. Mary’s for those killed, and the town had to pay a symbolic fine of a penny for every student killed, a practice that continued until 1825, 470 years after the riot. Finally, on the riot’s 600th anniversary, the then-current mayor was given an honorary Oxford degree; the school’s vice-chancellor was made an honorary freeman, and the hatchet was at last buried for good.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: Oxford was far from the only medieval university. Numerous institutions grew out of monastic schools across Europe, and became a model for higher learning, both religious and secular, the world over.

Further down the Wormhole: While town vs. gown riots largely died down in England after that fateful St. Scholastica’s Day, riots over other subjects have continued on to the present day. The 2011 England riots—precipitated by police shooting and killing Tottenham resident Mark Duggan—spread across the entire country, with 3,000 arrests made and five dead. Football (soccer) games in several leagues were postponed afterward, including an England vs. Netherlands game at Wembley Stadium. Britain’s largest stadium (and the second-largest in Europe), Wembley hosts the national team, the FA Cup Final, and was a major site at the 2012 London Olympics. It’s also been the home of American football’s forays abroad, hosting NFL games on and off since 1986, with a long-term eye toward putting an NFL team in London. However, another league got there first. The United States Football League, a rival league that made a run at the NFL in the mid-’80s, played a game at Wembley in 1984. As the XFL makes a second attempt at bringing pro wrestling’s panache to the gridiron, we’ll revisit the original springtime football league next week.