Antonioni’s Le Amiche is an early gem that scarcely resembles his later ones

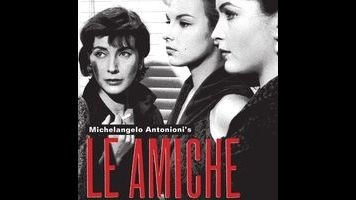

When a director settles on a unique vision of the world and then sticks to it forever after, early movies that don’t reflect that vision sometimes wind up forgotten or undervalued. Too Late Blues, starring Bobby Darin as a jazz musician, ranks with John Cassavetes’ best work; it rarely gets mentioned, though, because it doesn’t fit what we now think of as the Cassavetes template. Likewise, discussions of Bresson rarely focus on the superb Les Dames Du Bois De Boulogne, an early film he shot using professional actors rather than the blank “models” he’d later favor. To their ever vigilant credit, Criterion released Dames on DVD (though they have yet to upgrade it to Blu-ray), and next week, in a similarly perspicacious move, they’re adding Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1955 feature Le Amiche to the collection, even though Antonioni doesn’t truly become “Antonioni” until L’Avventura, two films later. Looking at the film with an eye toward what would follow, one can perceive seeds being planted, but it’s also just a gorgeously melodramatic outlier.

Unlike most of Antonioni’s films, which he wrote himself, Le Amiche (the title translates roughly as The Girlfriends) was adapted from a literary work, Cesare Pavese’s novella Among Women Only. It provides a clear identification figure in Clelia (Eleonora Rossi Drago), a woman of about 30 who returns to Turin, after years in Rome, to open a boutique. The building is still under construction, and Clelia finds herself at once attracted to and somewhat put off by Carlo (Ettore Manni), the architect’s assistant who reminds her of the working-class background she’s worked hard to leave behind. But Le Amiche’s most cutting social observations stem from a group of wealthy, indolent women, who Clelia meets by chance when one of them, Rosetta (Madeleine Fischer), attempts suicide in the hotel room next to hers. Quickly befriended by Momina (Yvonne Furneaux), the clear alpha female, Clelia gets drawn into a world that seems increasingly callous and meaningless, leaving her uncertain of where she belongs.

Compared to Antonioni’s subsequent portraits of general, unspecified malaise, the movie’s fairly accessible, though it doesn’t unfold as straightforwardly as the above synopsis suggests. (Strategic use of one especially frivolous woman, played by Anna Maria Pancani, helps to disguise how shallow the others are.) Antonioni shoots it quite differently, too—his celebrated films are fairly static, showing people dwarfed by landscapes and/or architecture, whereas here a mobile camera constantly creates new compositions in response to varying power dynamics among the characters. Mostly, Le Amiche dazzles with its diverse portrait of human frailty, making each of its women (plus a handful of relatively disposable men, including future L’Avventura star Gabriele Ferzetti) uniquely flawed and fascinating even as they collectively represent the struggles and neuroses of a particular time, place, and social stratum. It’s the same trick that George Cukor pulled off in The Women, to which this film is a sort of high-couture, dual-gender cousin. Would we revere Antonioni as much if he’d continued making expertly conventional movies like this one, rather than carving out a modernist aesthetic that transformed the medium? Probably not. But we might very well love that hypothetical guy, too.