Apocalypse pits the strengths of the X-Men series against the weaknesses

It’s 1983 in the X-Men movie multiverse, and that means more Cold War threats, more period fashions that skirt parody, and more barking about the future of super-human-mutant-kind. Ever since X-Men: First Class set the series’ clock back a few decades and installed Michael Fassbender’s moody Magneto and James McAvoy’s louche Charles Xavier as replacements for Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart’s chess-playing pappies, the big-screen X-Men’s central conflict—Xavier’s Booker T. Washington-esque School For Gifted Youngsters vs. a rogue’s gallery of evil mutants, crew cuts, and politicos—has gotten a lot murkier. For the franchise’s ballooning, unmanageable cast of mutants, picking sides now seems to have less to do with choosing between cooperation (which the recent movies implicitly distrust) and resistance, and more with whichever flashback-prone white dude’s overbearing savior complex works for you.

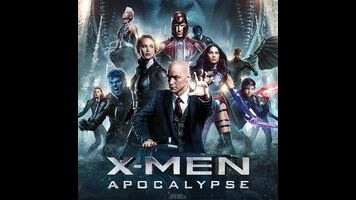

X-Men: Apocalypse, directed by series mainstay Bryan Singer, gives Magneto, the Holocaust survivor who can control magnetic fields, and Xavier, the paraplegic telepath who tends to come off as really smug, next-to-zero shared screen time. Alternate-timeline Earth may be under threat from the nuclear theatrics of the Reagan administration and the return of blue-skinned ancient Egyptian mutant Apocalypse (a bizarrely cast Oscar Isaac), but its nominal poles of right and wrong are bubbled away. At the start, the two are leading idyllic dream lives. Magneto has returned to his native Poland, where he lives quietly as an ironworker and family man in the last months of Solidarity. Xavier has his mansion full of young-people-in-need, where he plays the part of the undergrad crush object: shaggy hair, English accent, blazer hiked up to the elbow, Miami Vice-style.

Then everything goes to shit. Both perfect homes are destroyed—and yet the two men remain effectively passive, locked in hang-ups while assorted protégés and allies do all the duking out and legwork. Even Isaac, his face pinned in a look of hemorrhoidal discomfort by make-up and prosthetics, plays the would-be destroyer of humanity as insecure. When he finally goes mano a mano with Xavier at the climax, it’s in a psychic battle staged inside the latter’s dreamspace, which happens to look exactly like his mansion. In recent months, both Batman V Superman: Dawn Of Justice and Captain America: Civil War have offered up big, flashy superhero standoffs as feuds of ideology and stubborn will. Apocalypse, which looks and moves more like a comic book than either of those movies, says “no thanks” to all that, and instead delivers borderline-psychedelic displays of super-powered insecurity.

The X-Men films have made an explicit connection between the mutants’ powers and pubescent self-discovery, but perhaps it’s necessary to address the last few movies’ psychosexual subtext. The Xavier-Magneto conflict, ostensibly ideological, basically comes down to worries about inadequacy and masculine ego. Magneto, virile, has fathered more children than he even knows about in the Apocalypse timeline; he wears a purple helmet that is—let’s face it— kind of phallic, and his signature move is to rise slowly into the air. Xavier—first seen as an adult in First Class trying to pick up a woman in a bar—is impotent, at least metaphorically, and will eventually see all of his luxuriant hair fall out. He fills his mansion with surrogate children. He is also a voyeur, using his supercomputer Cerebro to peer around the globe. (The good professor does all this out of a wheelchair, for maximum Rear Window effect.)

These two men compete by reproducing—both literally and figuratively, as with so much in the movie—and by trying to win over a figure of all things feminine straight out of the dank recesses of the misogynist imagination: an unpredictable, ageless shape-shifter named Mystique (Jennifer Lawrence). Occasionally, they cross paths with the ideal of pure, hirsute manhood that is Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine. Here, they are confronted with the threat of ICBMs being launched by the United States and the USSR, and with Apocalypse, who reproduces asexually, moving his consciousness into a new body when necessary. Apocalypse also happens to be a Fagin figure, shuffling around the back alleys of Cairo, where he makes the weather-controlling pickpocket Storm (Alexandra Shipp) his first follower by offering her baubles. Just to make it clear what Singer and his team are going for, John Ottman’s opening credits march is arranged to sound exactly like the theme music from Tobe Hooper’s 1985 space-sex-vampire flick Lifeforce.

The key ingredient of Singer’s X-Men movies (X-Men, X2: X-Men United, X-Men: Days Of Future Past) is that they approach super-powers as power fantasies; there’s no moment in the cultural-conversation-saturating Marvel Cinematic Universe that comes close to Days Of Future Past’s “Time In A Bottle” slow-motion sequence, or even the older Magneto’s escape from a plastic prison in X2. In Apocalypse, extravagant effects cross lines of reality to express fears and desires: Magneto tears apart Auschwitz, using the bricks of the concentration camp to build an impossible futuristic cityscape of archways; Nightcrawler (Kodi Smit-McPhee), dressed in a red-and-black Thriller jacket, teleports away, as every awkward teenager wishes they could; Quicksilver (Evan Peters), still living at his own slacker-ish pace in his mom’s basement, stops time to save bystanders, eat pizza, and listen to the Eurythmics. In the comics, Apocalypse has the power to change size. Here, he can only do so in Xavier’s dreams.

But much of what makes X-Men: Apocalypse legitimately interesting also makes it frustrating and lopsided, since Singer and screenwriter-producer Simon Kinberg remain committed to the structure of an overlong comic-book blockbuster, complete with a climax in which the world has to be saved using as many different colors of energy beam as possible. That means handing over much of business of moving the plot to Mystique and to a group of youngsters that includes Cyclops (Tye Sheridan), Jean Grey (Sophie Turner), and the aforementioned Nightcrawler. It’s here that the movie series’ longstanding inability to create female characters as fleshed-out and conflicted as its men gets thrown into stark relief. However, the globe-trotting—which takes the movie from suburban malls to Eastern German underground clubs—gives Singer and Kinberg a chance to indulge their taste for period references, be it a well-timed Ms. Pac-Man sound effect or a discussion of Return Of The Jedi that lets the series take yet another kick at Brett Ratner’s little-loved X-Men: The Last Stand.