Apologies to It, but Gerald's Game shows how to really adapt a Stephen King bestseller

Stephen King is having a moment, and so is Mike Flanagan. Coming off of the positive critical buzz surrounding last year’s Hush and Ouija: Origin Of Evil, Flanagan decided to re-team with Hush producer Netflix for a film adaptation of Gerald’s Game. It’s not an easy sell: Not only is King’s book structured in such a way as to make it extremely difficult to adapt—much of it takes place inside the mind of the main character, Jessie (Carla Gugino), as she lies handcuffed to a bed, alone and unable to escape, after her husband dies mid-kinky sex—but it deals with some very challenging themes of sexual abuse and the silencing of women. Thankfully, Flanagan’s film is up to the challenge, thanks in large part to Gugino and her compelling performance, which deftly expresses emotions from panic to grief to despair to rage, sometimes all at once.

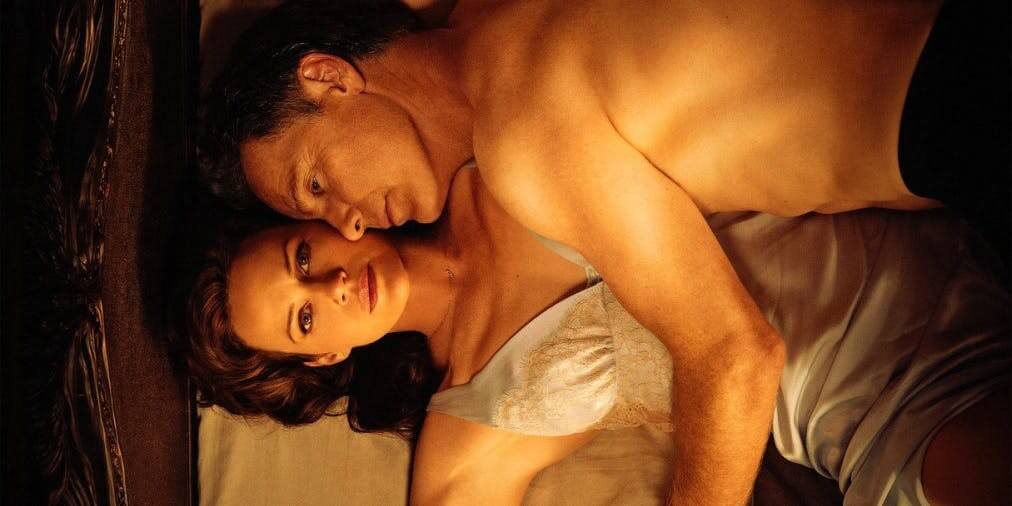

As the film opens, Jessie and her husband Gerald (Bruce Greenwood) are listening to a Sam Cooke song on the stereo of Gerald’s expensive sports car, on their way to the bourgeois lake house where they hope to reignite their 11-year marriage over $200-a-serving Kobe steaks. But before dinner comes a bit of pre-arranged bondage play with industrial-strength handcuffs, to which Jessie has hesitantly agreed in hopes of breaking a months-long dry spell. (Ah, married sex.) Her initial discomfort turns to panic when Gerald tries to pivot the scene into a rape fantasy; in the fight that ensues, Gerald—his bad heart under extra strain thanks to the Viagra he popped before their “game”—has a heart attack and collapses. Then the movie really begins.

Flanagan’s adaptation streamlines the storytelling in King’s novel, reviving Gerald as a hallucination early on to serve as the voice of every primal fear and traumatic memory that leaps to the front of Jessie’s mind as the hours turn into days. (The cleaning lady won’t be back for several days, and the nearest neighbor is more than a half mile away.) Before long, he’s joined by a stronger, more outspoken version of Jessie herself, who engages in a pitch-black verbal battle of the sexes with her husband’s shade as the real Jessie grows weaker and more afraid. Taking place entirely within one room, the film’s theatrical second act is a combination chamber drama and survival thriller, with dehydration, a vicious stray dog, and Jessie’s vision of an unearthly “Moonlight Man” occasionally interrupting her projected inner conflict. That conflict eventually takes Jessie back to a traumatic incident in her early adolescence, which took place at a lake house rather like the one where she’s now trapped.

Needless to say, things get really dark for a while. But Gugino’s emotional vulnerability and unshakeable will to live as Jessie keep the viewer invested in her (and thus the film) through these heavy sequences, whether it’s a harrowing flashback or a horrifyingly realistic gore prosthetic that will make even the most jaded viewers squirm. Flanagan’s directorial vision for Gerald’s Game is quietly assured, with intimate closeups and long periods of quiet—Flanagan deliberately avoids using musical cues during horror sequences, adding to the sickening sense of uncertainty—that put Gugino squarely at the center of the narrative. With her as our emotional anchor, the disturbing subject matter eventually comes around to something like hope, as Jessie finds her voice after a lifetime of manipulation and self-doubt. It’s melodramatic—the music that Flanagan tastefully holds back during the scare scenes comes out in full sappy force in the flashback sequences—but it’s also cathartic.

Unlike Andrés Muschietti’s recent Stephen King mega-hit It, Gerald’s Game stays faithful to the ending of King’s novel. (The film also leaves in references to Dolores Claiborne, The Dark Tower, and Cujo, cementing its place in the Stephen King multiverse.) And although Flanagan and co-writer Jeff Howard streamline it as much as possible, King’s digressive, exposition-heavy conclusion still necessitates some clunky voice-over that stands in sharp contrast to the rest of the film. (Let’s be honest: Stephen King is better at beginnings than endings.) Still, overall, Flanagan’s passion project benefits from his directorial style. As the renewed wave of interest in Stephen King continues to crash on our cinematic shores, we can only hope that future adapters and adaptations will be so well matched.