Approaching The Unknown is a monotonous space odyssey

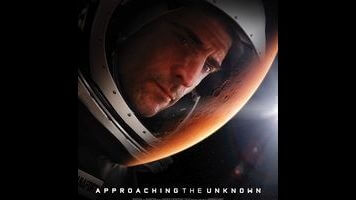

With his chiseled jawline, hawkish looks, and shaved head, astronaut William Stanaforth (Mark Strong) brings to mind an intrepid 1950s spaceman depilated by decades of cryogenic sleep. He is hurtling toward Mars, in a cramped spacecraft with a cargo of metaphors for futility and persistence, his one-way mission part early Space Age idealism, part death wish. Alone in space, he keeps fit with a rowing machine, even as his water purifier fails, promising death by dehydration before he can set foot on the arid Red Planet. He is going there to start a base for future astronauts, to be followed a few weeks later by Maddox (Sanaa Lathan). This mission—the first people on Mars, sent separately, never to return—doesn’t make a lick of sense, except as a part of a strained allegory for man, the unknown, and whatever else really serious sci-fi movies are supposed to be about.

Set largely in Stanaforth’s spacecraft, Approaching The Unknown sometimes feels like an ersatz The Martian, though it was filmed before Ridley Scott’s hit NASA-thon, from a script that was already kicking around screenwriting labs when Andy Weir started serializing his novel online. But while the two films share key ingredients (Mars, survival, a problem-solving engineer, etc.), the humorless, ruminative mood of writer-director Mark Elijah Rosenberg’s low-budget debut is a far cry from The Martian’s gung-ho paeans to teamwork and classroom science. Too high-minded to ever stoop to suspense or fun, Approaching The Unknown is almost completely interiorized, unspooling in voice-over narration that sounds like a writing exercise that got out of control. Initially, Strong’s deep voice lends it a shade of pulpy fatalism: “Mars is just a tiny dot in the sky 40 million miles away. Nothing lives there. Nothing has ever died there.”

But by the end, he’s saying things like, “Our bodies are more space than matter. What keeps us solid? Why don’t we dissolve?” No theme or parallel is ever lost on Stanaforth, a psychologically absent character who exists to comment on his own significance. As though trying to create depth via optical illusion, the movie has him mostly interact with characters who are literally flat and insignificant, communicating with the astronaut through little glitchy video screens. Stanaforth’s spacecraft is a womb, where he gestates during the nine-month journey to Mars; a self-made prison where he bides his time, dressed in a jumpsuit patterned with faint stripes; a primitive cave, where he grows a Stone Age beard as he fashions makeshift tools to fix his failing life support system; etc., etc. Surrounded by uncertainty and defeat, he keeps on, because that’s what symbolic figures do.

At least Approaching The Unknown has the look of thoughtful sci-fi down, from the tin-can interiors that suggest humanity’s smallness more than the vastness of the cosmos to the practical special effects, made with spaceship models and glass tanks of glycerin, powder, and dye. Rosenberg quotes Solaris and 2001: A Space Odyssey with misplaced confidence—the former during a stop at a space station of failed experiments, the latter whenever possible. But, like so many movies committed to “seriousness” as an aesthetic, it has an innate charm factor, typified by Strong’s one-note performance, his eyes locked in cosmic contemplation as though it were a dissociative thousand-yard stare. The final image speaks to the movie’s handmade appeal: Stanaforth, outfitted in a goofy-looking hunchbacked EVA suit, plodding through a suspiciously terrestrial-looking alien landscape to the magnificent sound of tinny synth strings.