Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret remains a guide for puberty

Now that she’s nearing the end of fourth grade, my daughter has become one of those bespectacled, bookworm types who collects straight As as easily as mosquito bites. So I was unpleasantly shocked to get an email from my daughter’s teacher, about a poetry assignment that I thought she had been excited about. For the final composition in the project, the “wish” poem, my daughter wrote: “I wish I had enough patience to finish writing this stupid book so I can freaking publish it.” Granted, living in our house where both of her parents swear like dock workers, we were lucky to get away with “freaking.” But the teacher was dismayed by this outburst from her favorite student. My husband thought it was hilarious. I was mostly dumbfounded, and asked the teacher if my daughter had been exhibiting any other behavioral changes at school?

The teacher’s response struck icy terror into my heart: “Usually when I start seeing students change… puberty is kicking in.”

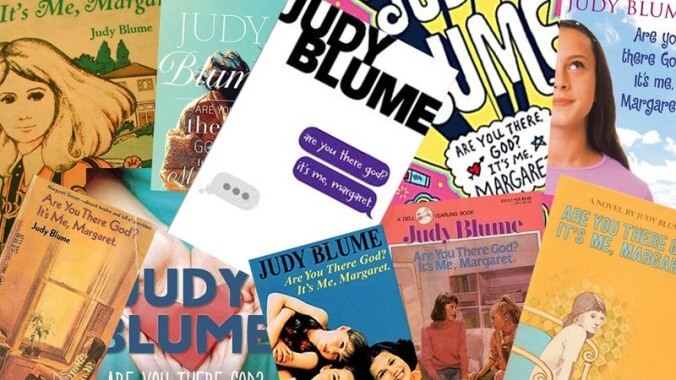

I fled to our neighborhood book store and quickly procured what had been my own puberty guide book: Judy Blume’s Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret? In sixth grade at my torturous Catholic grade school, we girls smuggled it around among ourselves like the contraband it was. We likely shouldn’t have worried; the nuns might have even approved, as it had God right there in the title.

Why did Are You There God spread like a beacon of truth throughout the female half of my middle-school class, and so many classes before and after it? It seemed to be the very first one to tell us what we were in for. Training bras. Sanitary napkins. Kissing games. They were all still ahead of us, but in the ’70s, there weren’t a lot of frank sit-downs with parents about our upcoming bodily changes. My school’s version of the “sex talk” was to have someone come in and tell us to never, ever go to Planned Parenthood, that it was an evil place. And the burgeoning genre of young-adult fiction favored heroic sagas over drugstore talk. We used Margaret like a travel guide, and even though girls have access to a lot more information now, I hope they still do. Also, since puberty seems to be kicking in even earlier now—due to the hormones in the milk, or something—even though my daughter is about a few years younger than I was (and about a year younger than Margaret in the book), I decided to err on the side of jumping ahead a few spaces, which I have the tendency to do.

I purchased two copies of the book, one for each of us, but as it turns out, I needn’t have bothered: I read it in a few hours, so much of it was still ingrained in my brain. I remember random complete sentences by heart: “I sunbathed, thinking it would be nice to start school with a tan” or “Grandma smelled delicious.” For as much as my middle-school self is trained on Margaret’s bust-increasing exercises and party kissing games, it is, as the title indicates, at heart a story of a girl’s search for spirituality. Young Margaret moves from the city to the suburbs with her parents right before she starts sixth grade. Her father was raised Jewish and her mother was Catholic; when both sides of the family protested their union, they eloped, and gave up religion altogether: “My mother says God is a nice idea. He belongs to everybody.” Now Margaret is in a close-knit community where everyone either goes to the Jewish Community Center or the Y, so without a religion she feels like an outcast.

But in this turbulent time of her life, Margaret has already created a sort of religious solace for herself, talking to God whenever she has a problem she doesn’t know how to deal with. In an effort to get closer to him, she goes to temple with her beloved grandmother, Sylvia; church with her friend Janie; and Christmas Eve Mass with her other friend Nancy. But she finds that she feels closer to God when talking to him in her own bedroom than within the trappings of religion.

The novel basically takes us on a straight path through Margaret’s sixth-grade year, starting right before school and ending at the beginning of the following summer. Margaret is a fairly mild persona, easy for a lot of kids to relate to, especially as she tries to fit in with a new crowd. Besides Gretchen and Janie, who are a lot like Margaret, there’s Nancy, the terrifying embodiment of a sixth-grade mean girl that unfortunately most of us can easily recognize. Nancy calls all the shots in the club meetings of the Pre-Teen Sensations, dictates what the girls wear (penny loafers, but no socks), is the only one who doesn’t wear a “baby bra,” and in the most heinous act possible to Margaret, lies about getting her period first.

But what Nancy does that’s most destructive—to the most heart-tugging character to me re-reading this book now—is spread rumors about Laura Danker, the first girl to develop in her class. I’ll never forget the first girl who wore a bra in my sixth-grade class—we had to wear white uniform blouses, so it was pretty obvious—and the poor girl just blushed and kept her head down all day. We all bought them after that. But in the book, Laura is completely ostracized, not only due to the way she looks, but because of the rumors that were spread, giving her what Nancy calls a “bad reputation,” even though Nancy’s the one that’s helping to create it. Nancy’s dickhead brother tells everyone that she goes behind the A&P with him and his friend Moose, and Margaret is so naive that she accepts this information without question. She’s also fiercely jealous of Laura for getting this kind of attention, as she has a crush on Moose herself.

So about halfway through the book, when Laura and Margaret are at the library and get into an argument about a school project, Margaret snidely repeats the rumors she heard from Nancy. A furious Laura calls her a liar and a pig, and yells, “Think about how you’d feel if you had to wear a bra in fourth grade and everybody laughed and you always had to cross our arms in front of you. And about how the boys called you filthy names just because of the way you looked.”

By having Margaret call out Laura the same way Nancy does, Blume is not only showing that our heroine isn’t perfect, she’s also showing the dangers in believing in such painful gossip, and how even a throwaway line at the lunch table can still hurt a lot when you’re on the receiving end. And that there’s no reason to think that Laura is “fast” just because her body has developed sooner. A distraught Margaret tries to apologize, but again, in Blume’s candid realism, atypical for the time period, Laura doesn’t really accept it, and heads off to confession (making her actually more devout that many of the other girls in her class). Margaret, continuing to fumble toward spirituality, thinks that maybe confessing will also help her feel better, but she can only mutter an “I’m sorry” before running out of the church. In a later-era book, Margaret and Laura might have become friends, or Margaret might have stuck up for her, but we don’t get this kind of resolution here. Margaret does go after Moose for claiming that he took Laura behind the A&P, but of course, it was never him anyway, only Nancy’s horrible brother. Moose cautions her against believing everything she hears.

Another Laura appearance that struck me so strongly on this re-read is in the famous “two minutes in the bathroom” sequence. In this version of “post office,” the kids call numbers and go into the bathroom. Laura calls the number of Philip Leroy, the most popular boy in the class due to how good-looking he is. It’s just a short line: “When they came out, Philip was still smiling but Laura wasn’t”—so you know that poor girl got groped in the bathroom. My daughter and I were talking about the book on the way home from school and her twin brother asked, “Who’s Philip Leroy?” My daughter said, “Oh, only this jerk that everyone likes for no reason.” I’ve scarcely ever been prouder. Unlike other Blume love interests like Deenie’s Buddy or Sally J. Freedman’s Peter, Philip Leroy has absolutely no redeeming qualities, and functions as a cautionary message from Blume to not like somebody just because of the way they look. On Margaret’s birthday he gives her a pinch to grow an inch “and you know where you need that inch!” He’s a creep.

In fact, that’s what’s fascinating to me overall about Are You There God: the lessons I was undoubtedly absorbing without realizing it. Nancy herself is a complicated test about what a true friend is and isn’t: Margaret fortunately eventually realizes that Nancy and Philip Leroy “deserve each other.” Margaret starts the book as a shy, somewhat docile girl who eventually winds up getting mad at everyone. She blows up at her parents twice, once for fighting in front of her and another time during her other grandparents’ disastrous visit when they discover that she‘s not Catholic. She tries to turn in her religion project to her teacher, but runs away crying: “What was wrong with me anyway? When I was eleven I hardly ever cried. Now anything and everything could start me bawling.” Besides the physical changes we were going to have to worry about it, we also endured the roller-coaster emotions we were starting to experience, the ones that I’m now getting a glimpse of in my daughter.

What I still love about this book is how forthright it is. The Newbery winners we had to read in class at the time were titles like Julie Of The Wolves and Call It Courage, sagas that had little to do with the everyday problems we were dealing with. I had kids in my class just like the ones in this book; I could absolutely tell you who the Philip Leroy was, the Laura Danker, the Norman Fishbein. Margaret‘s mother is horrified when she learns that Margaret’s new teacher is a man, an event so unusual that it needs to be commented on. My seventh-grade lay male teacher received the same treatment.

But when it comes to what’s really happening during this critical year, Blume lays it out coldly in a pivotal PTS meeting. Gretchen is the first one of the four girls to get her period, and has been commanded to tell the rest of the club all about it, down to having to keep a washcloth in her pants while her mother goes to the store for mini-pads. She tries to squirm out of it, but Nancy gets mad: “Look Gretchen, did we or did we not make a pact to tell each other absolutely everything about getting it?” For girls not receiving this information anywhere else, Are You There God was like a lifeline. Although Blume has changed the original details in her book to align with updates in feminine hygiene products (when the book was first published, the girls used belts for their sanitary napkins instead of the current adhesive types) the deciphering of the cryptic world of almost-womanhood remains Margaret’s most valuable asset. In this book, or the bullying in Blubber, the masturbation conversation in Deenie, the wet dreams and random erections in Then Again, Maybe I Won’t, and the loss of virginity in Forever (a book my best friend and I read in eighth grade and then immediately wished that we hadn’t), Blume was taking every adolescent’s most hidden fears and exposing them. By doing so, she assures generations of young people over and over again that what’s happening to them, even though it seems completely foreign, is also completely natural, and normal.

My daughter loved Blubber and all the Fudge books, but she may need another year or so to really appreciate Margaret. She calls certain parts of it “awkward,” like when Margaret’s friends get her to steal one of her dad’s Playboys, or the kissing scene. Because I was afraid that she might in fact get her period before I had a chance to explain it to her, I made her sit down with me to have the talk; it was an uncomfortable conversation that I know she would have rather avoided, but it was better than what that opposite result would have been. And I hoped that reading about Margaret and her friends’ conversations about it would help demystify it even more (she’ll also get her own puberty talk at school, like when Margaret and her friends had to learn about “mens-troo-ation,” before her grade ends this year).

Margaret has opened up some avenues of dialogue for my daughter and me, like it has for women of all ages for decades. We were recently discussing a scene in the book, and her brother again wanted to know what we were talking about. “You won’t get it,” she told him. ”You’re not a girl.” She may (fortunately) still be a few years from adolescence, but she already understands that much.