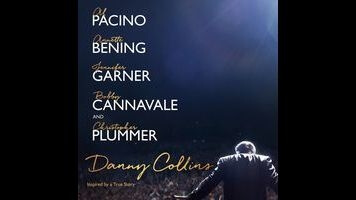

As the aging pop star of Danny Collins, Al Pacino is better than he’s been in years

Danny Collins’ title character is a pop crooner, pushing 70, who floats along, trailed by a colorful scarf and a mist of booze and cocaine. Never mind that Al Pacino, who plays Danny, couldn’t carry a tune if his life depended on it. What he captures is the essence of the aging celebrity who’s always on. He treats every person as though they were an audience and he were expected to keep them entertained. This is the kind of thing that should come effortlessly to Pacino, one of the all-time greats of American acting, but no longer does. In fact, this qualifies as his best and most easygoing film performance in a good decade.

At first glance, Danny Collins seems like one of those classic boomer fantasies of reinvention and reconciliation, the kind where old guys learn how to make up for lost time. Danny—still selling out 5,000-seat theaters and greatest-hits shows—gets a “What do you get the man who has everything?” present from his manager (Christopher Plummer) for his birthday: a personal letter from John Lennon, sent in 1970, but never delivered. Gazing out across his mansion—effectively, at the past 45 years of his life—Danny decides to start over. He boards his private jet, flies out to New Jersey, and checks into a suburban Hilton; quits drugs; has a grand piano hauled into his hotel room to work on his first original song in 30 years; flirts ceaselessly with the Hilton manager (Annette Bening); and shows up unannounced at the doorstep of the grown son (Bobby Cannavale) he fathered with a groupie decades ago and abandoned.

Throughout, Danny never stops asking people’s names and cracking jokes; he’s a showman and this show is for him. He acts like a multi-millionaire fairy godmother, giving away luxury cars, trying to set strangers up on dates, and driving around in a tour bus with his own smirking face printed on the side. Which is to say that Danny is the embodiment of a certain fantasy, not just of being able to turn around your own life, but to gift improvement and fix others’ lives.

The unique thing about Danny Collins—a light, unexceptional-looking comic drama that’s carried in large part by its cast—is how it sets up this conventional, sentimental resolution, but then refuses it. The directorial debut of Dan Fogelman, writer of Crazy, Stupid, Love and Last Vegas, the movie combines the compulsive sub-plotting of the former with the retirement-age asides of the latter. (Eighty-five-year-old Plummer’s wardrobe—tight black T-shirt, slim-fit jeans, crushed-velvet blazer, and a trilby he never takes off—almost qualifies as a joke in and of itself.) But it then takes those elements in an uncharacteristically realistic direction.

This is the story of an aging pop star trying to get sober, find creative fulfillment, start a new romance, become the father and grandfather he never was, and—in a twist that feels mawkish, until it doesn’t—help someone confront a possibly terminal illness; the unusual thing is that it recognizes that its not-quite-hero can’t do most or maybe even any of these things. It begins as pure fantasy and gradually grounds itself, ending on a graceful note that’s almost completely unexpected.