It’s 1984, and pre-teen Aria (Giulia Salerno) is caught, along with her two step-siblings, between their parents, an egotistical actor (Gabriel Garko) and a mercurial pianist (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who have elevated bitterness and recrimination into a blistering, around-the-clock art form. Given Argento’s own background as the scion to a showbiz family, it’s possible to see these early scenes—in which Mom and Dad verbally lay waste to each other in earshot of their offspring—as a critique of what fame and celebrity can do to warp a family dynamic. Yet the tone is more comic than anything else.

Argento seems to want us to see the humor in adults acting more childishly than their offspring. And for a while, it is funny, mostly because Garko and Gainsbourg throw themselves into their roles with a kind of voracious vanity. They’re oblivious to their own monstrousness, and Gainsbourg, who has become one of the most uninhibited actresses around, reaches down deep to play a woman whose maternal instincts have been buried under layers of hard-earned narcissism.

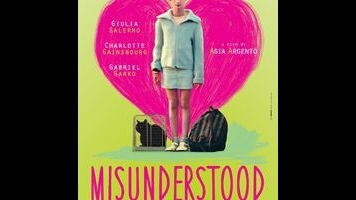

The question of whether Aria will ultimately take after her parents or forge a path away from their bad habits gives Misunderstood its basic dramatic shape. After shuttling back and forth between residences and holidays, Aria starts to feel manipulated and unloved and acts out accordingly. Her intense friendship with a classmate (Alice Pea) suggests both her need for affection and her difficulty expressing those feelings appropriately; she acts, in fact, like her parents. The girl is damaged, and yet Argento insists on treating her behavior as if it’s devastatingly cute and/or rebellious—as is she’s a defiant, resourceful waif.

This may be the director’s idea of a self-portrait, and if so, it’s at once self-pitying and self-flattering (never more so than in the misguided final moments, which take the form of a direct, confessional address to the audience). As an actor, Argento can be wonderfully forward and fearless, but here it feels as if she’s straining for effect, especially in the garishly over-saturated color palette. The ostensible boldness of Misunderstood is undermined by the sense that it’s also pandering—that its view of childhood as a bourgeois horror-show is at least as salable on the art-house circuit as it is authentic to its creator’s experiences.