At its best, Under The Gun finds nuances in the gun-control debate

It’s a measure of how little has changed regarding gun control in America that, 14 years after Michael Moore’s Bowling For Columbine, Stephanie Soechtig’s Under The Gun is yet another documentary about the issue inspired in large part by mass shootings. For Moore, the 1999 Columbine High School massacre in Colorado was the jumping-off point, while for Soechtig, it’s both the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, and the Aurora, Colorado, movie-theater shooting. But the basic underlying issues remain sadly similar. Debates over the necessity of universal background checks, the National Rifle Association’s outsized political power, the income inequalities leading many inner-city gun-related tragedies to be ignored: All were present in Moore’s film and continue to be elaborated on in Soechtig’s.

The major difference between the two lies in presentation. Moore approached the subject with his usual mix of thoughtfulness and bluster, mixing information and insights with grandstanding stunts and a blatantly partisan edge. Soechtig—under the guiding light of executive producer/narrator Katie Couric, who worked with the director on her last nonfiction film, Fed Up—takes a more conventional issues-documentary approach: copious talking-heads interviews, statistical information presented through cutesy animation, and gestures toward journalistic balance.

But for all its surface sobriety, Under The Gun only takes balance so far. When a voice from the anti-gun-control side is heard, a dissenting voice follows. When a housewife in Temple, Texas—who proudly carries a rifle wherever she goes about her business in town—expresses skepticism toward the possibility of people getting shot in supermarkets, the film immediately presents the case of Gabrielle Giffords, who was a member of Congress when she survived an assassination attempt at a Safeway in Tucson in 2011, and still deals with some paralysis as a result. Same with members of the Virginia Citizens Defense League who express fears that the government will take away their guns as a result of restrictive legislation. Right away, Soechtig and Couric bring in an expert to roundly debunk their claim. On the filmmaking front, Soechtig isn’t above the occasional easy joke, either: A sequence of footage from a gun show in Richmond, Virginia, is ironically scored to Léo Delibes’ romantic “Flower Duet.” And Brian Tyler’s score is used to excessively underline emotion, injecting action-movie-like menace in sequences meant to condemn the NRA, and laying on the twinkly major-key keyboards in more triumphant moments.

Thankfully more prominent are the moments when Soechtig and Couric are willing to acknowledge the nuances within both sides of the debate. “We’re all friggin’ responsible,” says Richard Martinez, the father of one of the victims of the Sandy Hook shooting, acknowledging the sad truth that only after the tragedy hit home for him was he finally inspired to take action. And in one of the film’s more eye-opening segments, many NRA members randomly questioned on the street vocally express their support for background checks—something you might not might expect if you take NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre’s many public comments against background checks to be representative of the position of the group as a whole.

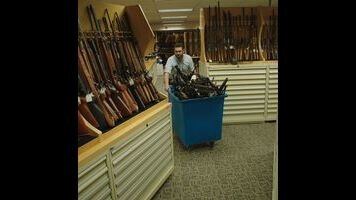

Ultimately, Under The Gun does have a clear argument to advance through its densely packed 105 minutes, and the NRA is at the heart of it. Originally created in 1871 to promote better marksmanship, it has gradually transformed into the powerful lobbying organization it is now, frequently decrying attempts to legislate gun ownership even after the Newtown and Aurora tragedies. Its reach is far deeper than just Wayne LaPierre’s public statements, however. According to Soechtig and Couric, the NRA exercised its power in 1986 to hamper the efficiency of the Bureau Of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms And Explosives through successful legislation that ensured the ATF could not computerize gun-ownership records. The organization also boycotted firearms-maker Smith & Wesson in the 1990s for trying to make smarter guns, forcing the company to sell the kinds of bigger assault weapons that criminals like Adam Lanza and James Holmes would later put to deadly use.

Under The Gun is admirably detailed in tracing the NRA’s insidious influence not only in the halls of power, but in the minds of its supporters, some of whom fully buy into the organization’s message that government regulation of gun ownership is equivalent to a form of control through denial of their Second Amendment right to bear arms. But its most effective tactic in damning the NRA is its use of heartbreaking personal stories of those who have lost loved ones in gun violence. Much screen time is devoted to Jessica Ghawi, one of the victims of the Aurora movie-theater shooting and an extroverted life-force of a personality killed before she had a chance to fulfill her sports-broadcasting aspirations. Her stepfather, Lonnie Phillips, keeps a shotgun at home, which he says makes him feel safe; that was hardly enough, though, to protect Jessica from James Holmes’ trigger finger. Such tragic anecdotes put a human face on this still-polarizing issue and serve Soechtig and Couric’s broad argument in Under The Gun better than any heavy-handed music cues and animated statistics ever could.