A nude swimmer, hunky like an underwear model, slits the surface of a pond at dawn. Next, we see him dressed, answering a phone call from a man (his boyfriend, maybe?), something about remembering to take his medication. He slips a canoe into a river, only to be caught in rapids and rescued by two Chinese hikers lost on a Christian pilgrimage along the Way Of St. James, who string him from a tree in rope bondage and threaten to castrate him. He slips away into the woodland and happens across a cult of pagan mummers who saw off a boar’s head by torchlight. He goes skinny-dipping with a deaf, goat-teat-sucking shepherd named Jesus. He is shot by topless huntresses in a forest clearing. And like the jokes goes, “What do you call this act?” “The Ornithologist.”

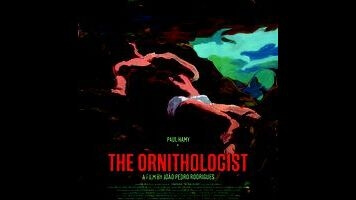

To be fair, the title of the new film by João Pedro Rodrigues (To Die Like A Man, The Last Time I Saw Macao) is both sincere and descriptive, as its regularly undressed hero, Fernando (French actor Paul Hamy, whose voice is dubbed by Rodrigues himself), is a Portuguese ornithologist who has gone into the wild to study local species of stork and vulture. In Rodrigues’ obscurantist and presumably very personal narrative, which bears disconcerting similarities to a grating American indie called The Catechism Cataclysm, he is also an allegorical stand-in for the Catholic patron saint of lost things, St. Anthony, who was also born Fernando. Rodrigues, who studied ornithology before taking up film, identifies with this figure enough to not only voice his version of St. Anthony, but to also eventually take over the role later in the movie, as the rechristened “António” has a trippy encounter with a reimagining of Thomas (Xelo Cagiao, who also plays the shepherd named Jesus), the identical twin brother of Christ in the gnostic apocrypha of the early church.

But while it’s always nice to see artists expressing themselves, one can’t help but wish for something more exciting than a slow-moving, academic (though definitely not humorless) exercise in pseudo-blasphemy that won’t be seen by anyone who it might shock and won’t surprise anybody who’s spent more than a few days around a trendy film festival sidebar. Still, even if The Ornithologist doesn’t amount to much of an allegorical or mystical experience, it’s reliably watchable as an attempt at creative devotion. Whether it’s in painting, music, or architecture, the underlying idea of religious art has always been to express ideas about divinity and transformation through conceptions of beauty, and Rodrigues sticks to what he appears to know and love: explicitly eroticized male nudes (especially Hamy, cast for looks); wildfowl and birds of prey; the more primeval stretches of the Portuguese landscape. All these are invested with implicit significance through his camerawork—an effect that is unfortunately dispelled whenever he breaks out the more familiar Christian symbolism of stigmata and white doves.

Like so many of the major arthouse filmmakers who have come out of Portugal, including Pedro Costa (Colossal Youth, Horse Money) and the late João César Monteiro, Rodrigues has the kind of internalized relationship to classic American cinema that would put their American peers to shame, with the films of Nicholas Ray being a particular favorite. As The Last Time I Saw Macao referenced Macao (credited to Josef Von Sternberg, but directed in large part by Ray), The Ornithologist seems to riff obscurely on the landscapes and waterways of Ray’s mythopoeic, proto-environmentalist Wind Across The Everglades, in which a game warden faced off against bird poachers in early 20th-century Florida. There’s plenty to be said for the relationship between religion and the roots of European cinephilia; for the rich tradition of queer filmmakers, be it Pier Paolo Pasolini or Derek Jarman, finding new terms for the lives of the saints; and for the importance of secret and coded meanings in Christian art. But perhaps The Ornithologist lends itself so well to scholarly unpacking because it has too little of its own to offer. Maybe it’s healthier to just enjoy the light bouncing from the water to Hamy’s abs.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.