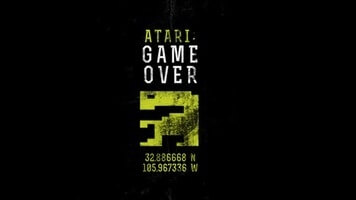

Atari: Game Over is a nostalgic excavation of video-game history

Although it runs only a little over one hour, Zak Penn’s Atari: Game Over is actually two documentaries in one. Roughly half of its running time is given over to a history of the meteoric rise and fall of Atari, the company that cornered the video-game market in the early ’80s and won the hearts and minds of Generation X in the process. The rest is devoted to the 2014 excavation of a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico, where legend has it Atari buried millions of copies of its failed video game based on Steven Spielberg’s E.T. Penn’s film is far more compelling when it sticks to the history lesson and stays out of the dump.

Penn has written a number of Marvel movies, but as a director he’s probably best known for Incident At Loch Ness, the mockumentary in which he teamed with Werner Herzog to investigate the mystery of Nessie. The Alamogordo video-game graveyard is another urban legend that grabbed Penn’s attention, and if your first instinct is that it doesn’t sound anywhere near as interesting as a monster living in a Scottish lake, you’re right. Nerd lore has it that E.T., known to many as “the worst video game of all time,” was such a colossal failure that it took Atari down with it, and that the company buried millions of unsold cartridges in the dead of night as if cleaning up after a mob hit.

The truth of the matter is a bit more nuanced. Atari rose to prominence in the ’70s, first with Pong, the most primitive possible game that nonetheless became hugely popular, followed by a variety of coin-operated hits. Atari was bought by Warner Communications in the late ’70s, and soon launched the home console that would become popular beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, the 2600. Introduced with nine cartridges in 1977, the 2600 and its games propelled Atari to $375 million in profits by 1981, making it the fastest-growing company in American history. Its headquarters in Sunnyvale, California, populated by eccentric, hard-working, and hard-partying programmers, pioneered the Silicon Valley aesthetic, and it’s no exaggeration to say that Atari paved the way for the home-computing revolution.

One of those programmers, Howard Warshaw, is the most interesting figure in Penn’s film. A week after being hired by Atari in 1981, Warshaw was asked to do a 2600 conversion of the popular coin-op game Star Castle. Instead, Warshaw took the fun elements of the game and reconfigured them into Yar’s Revenge, which became a million-seller and one of Atari’s most beloved games. That led to a gig adapting Raiders Of The Lost Ark for the console, which eventually led to Warshaw agreeing to program an E.T. game in only five weeks in order to meet a Christmas deadline. (At the time, the average game took nearly six months to complete.)

Atari had gambled big on E.T., paying a rumored $22 million for the rights, and the Christmas deadline was a hard and fast one. What Warshaw delivered met with Spielberg’s approval and was another enormous seller at Christmas, but Atari had produced too many of the cartridges and the game was not beloved enough to become a perennial seller. Atari was stuck with millions in returns and Warshaw was stuck with the reputation as the man who made the worst game ever. Still, Atari’s real downfall had less to do with E.T. specifically than the mindset that led to its creation; the company kept pumping product into a saturated marketplace, and by 1983 its losses were mounting in the hundreds of millions.

This story is told in breezy fashion in Atari: Game Over, mainly by the drily humorous Warshaw and the amiable Manny Gerard, a former CEO of Warner Communications. If anything, it’s too breezy; the brief history here whets the appetite for a more in-depth examination of the Atari age. Instead, Penn turns his attention to the efforts of New Mexico garbage contractor Joe Lewandowski to unearth the legendary cache of buried games. Lewandowski’s quest is hampered by red tape (environmental groups are understandably skittish about hazardous waste in the landfill, including mercury-laced hogs) and the ravages of time (pinpointing the exact location is, as Penn puts it, “like finding a haystack in a bunch of other haystacks”), but eventually the date is set. The dig becomes a sort of nerd Woodstock, with geek luminaries like Ready Player One author Ernie Cline (as well as Warshaw himself) traveling hundreds of miles to see the unveiling.

For the most part, it’s a depressing display. Nerds of a certain age are so precious about the pop-culture artifacts of their youth, it’s tempting to see this gathering of hundreds in a dump full of discarded ’80s detritus as an apt visual metaphor. The spectators see it in more mythic terms, however; more than one enthusiast compares the dig to Raiders Of The Lost Ark, and a sudden sandstorm evokes the opening of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind. Everyone here speaks fluent Spielberg. (It’s fitting that Penn is adapting Cline’s Ready Player One, a book heavily steeped in vintage video games, as a screenplay for Spielberg to direct.) Penn keeps inserting himself into the action, playing the role of the buffoonish Hollywood guy who knows nothing about archeological excavations, and he’s usually not as amusing as he’s trying to be. When the revelation finally comes, it’s underwhelming to say the least. Yes, there are E.T. cartridges buried in Alamogordo, but not millions of them, and there are plenty of more popular games buried there, too.

If the dig is worthwhile at all, it’s for Warshaw’s emotional reaction to seeing the outpouring of affection for his long-buried work. Atari: Game Over tries to make the revisionist point that E.T. was actually a very good game, especially considering the circumstances of its creation. That’s a dubious claim, but there were certainly far worse games made for the 2600. (I recall the home conversion of Pac-Man being much more disappointing than E.T., for instance.) Warshaw deserves recognition for pushing the limits of early ’80s technology, but the exhumation of his final work makes a garbage mountain out of a molehill.