Atlanta takes on the anti-CRT crowd with a darkly satirical spin on reparations

"The Big Payback" departs from the crew's European tour, but it's a diversion worth taking

The last two episodes of Atlanta have followed Earn, Al, Darius, and Van on the first legs of a European tour. Episode four diverts the action back to the titular city, away from the main foursome and into an unrelated story (the same approach taken by the season opener, “Three Slaps”). It’s hard not to feel a bit cheated by these anthology-style episodes: Atlanta’s primary quartet are as well-written and portrayed as any characters on TV, and I always want to spend more time with them. (I’m still having trouble processing that season four will be the show’s last.) But this detour—a dark satire that tackles systemic racism and the concept of reparations, laying bare the worst nightmares of the anti-CRT brigade—is absolutely worth taking.

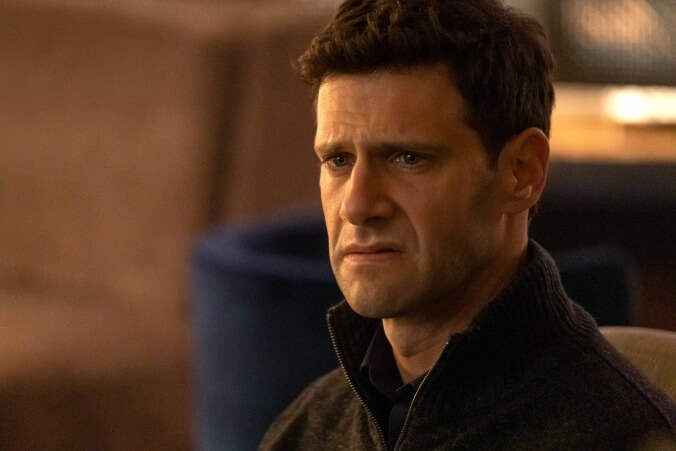

The episode opens as we follow Marshall (guest star Justin Bartha) in line at a coffee shop. AirPods in place, he absent-mindedly slips some cookies into his jacket pocket as he witnesses a confrontation between the cashier and a Black customer. Marshall gets his coffee and goes on scot-free, while the other man goes to the back of the line. It turns out Marshall is a separated dad; as he’s driving his daughter to school, he hears a radio news story about a Black man who’s successfully sued a Tesla investor because his ancestors enslaved the plaintiff’s forebears. It’s a development the anchor notes could have “wide-ranging” implications, “especially in America.” (By the way, a lot of plot and spoilers of the episode follow, but they’re worth unpacking.)

At the office, Marshall’s co-workers express disbelief and concern at the story, while layoffs are announced; his company is being sued for the same reason. His white co-worker says she’s researching her family tree online—”everyone is”—while observing of their Black colleagues: “Lucky them—not a care in the world.”

At home, Marshall is confronted at his front door by a Black woman, Sheniqua Johnson (Melissa Youngblood), who is live-streaming on her phone that Marshall’s ancestors enslaved hers, he owes her money, and she’ll probably take his house. She later shows up with a bullhorn outside his office, demanding a payout.

This is beyond-heavy stuff, but it’s deftly written and directed. Many moments in this script (by Francesca Sloane) would do Paddy Chayevsky proud, particularly when Marshall seeks counsel from a Black co-worker and his estranged wife won’t let him see their daughter because of his ancestral past. “I’m Peruvian,” she says. “This never would have happened to me!” Marshall protests: “You were white yesterday!” His wife replies that they have to make the divorce official because “I can’t have my finances take a hit.”

Relegated to a hotel because Sheniqua and several compatriots have camped out on the lawn outside his apartment, Marshall turns on the TV and sees a law-firm commercial, shot in classic ambulance-chaser style, urging anyone eligible to claim their cash. (It’s another moment worthy of Network.) In the lobby bar, Marshall meets a man (“Ernest”—homophonically the same as Donald Glover’s character, of course—“call me E”) who says he’s “in the same boat … you owe a lot.”

“Two days ago, I had a good life, and now I’m being fucked by some shit I didn’t even do,” Marshall complains.

The lobby man (a riveting Tobias Segal) reveals that he’d recently been clued into some realities about his own grandfather, a man always sold as part of the “pulled himself up from his own bootstraps” myth: “Turns out he had a lot of help—and a lot of kids.”

“We don’t deserve this,” Marshall says.

“What do they deserve?” E replies. For Black people, he says, slavery is not past and has a monetary value that keeps compounding. But as white men, they’ll be okay. “We’re free,” he says, before stepping outside and shooting himself in the head. My first impression was that this was a misstep, an instance of over-egging the dramatic batter. His monologue—with its premise that white men are privileged even when they’re down-and-out—was powerful enough. But the ending of the episode made it feel justified. Some people can bear certain truths, and some people can’t.

Ultimately, we see that Marshall is working in a restaurant, where 15 percent of his paycheck is going to “restitution taxes” paid to Sheniqua. In a poignant moment, we’re taken through the kitchen, where nearly everyone on the line is a person of color. Marshall, of course, is a waiter, an acceptable face for the front-of-the-house, and the episode closes with him serving ritzy dishes to a Black party.

Hiro Murai’s direction is stellar, as usual: He knows how to make irony land without hitting you over the head, and the performances are perfectly modulated. Segal is a standout, and Bartha is very effective as a hangdog everyman avatar who’s just letting life happen to him—trying to do the right things on the surface, but not doing too much to right the wrongs. This episode and “Three Slaps” are so dramatically rich that I’d like to see the Glovers and Murai launch an anthology series of their own, an updated Twilight Zone. No need to brand it as sci-fi or horror. Modern life is just a step or two apart.

For a show labeled comedy (for lack of a more apt genre), “Big Payback” isn’t a fun 30-plus minutes, but it is great television. Atlanta is tackling the big, uncomfortable questions no one else would dare—namely, can we resolve systemic racism and reconcile this country’s history with slavery, when some won’t even acknowledge either—and this episode is worth spending time with. Unfortunately, the people who most need to consider its themes won’t see it; they can afford to turn away.

Stray observations

- Another good moment: Marshall claims his background is “Austro-Hungarian…we were enslaved too” (to the eye-rolling of his co-worker). But he’s not interested in researching the truth about his ancestors.

- E’s lobby-bar monologue is exceptional writing. “We’re treating slavery as if it were a mystery buried in the past, something to investigate if we chose to. That history has a monetary value. Confession is not absolution,” he says, and for Black people, slavery is not past—it’s “a cruel, unavoidable ghost that haunts in a way we can’t see.”

- Episodes two and three of this season were so moody and evocative that I keep finding myself thinking about where the main characters are—a fortunate/unfortunate consequence of watching a show that unspools week-by-week and is unbingeable.

- The writing in the first four episodes of Atlanta is better than I’ve seen in any drama this season. But it’s a 30-ish minute show, so where do the scripts for “Three Slaps” and “The Big Payback” get submitted? Is there a way to diversify the Emmys’ rigid comedy-drama dichotomy (which has punished some excellent-but-ambiguous 30-minute shows in recent years)?