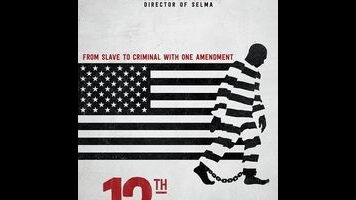

Any social-issues documentary worth a damn has at least one moment—one statistic, one anecdote, one archival snippet—destined to boil the blood of its audience. But in 13th, the new nonfiction film from Selma director Ava DuVernay, those agitating moments keep coming and coming, one after another, creating a blitzkrieg of outrage. The title refers to the 13th Amendment, which officially abolished slavery in 1865, “except as a punishment for crime.” The film argues that this particular choice of words became a free-labor loophole in the South, creating incentive to lock up black men on minor charges and to paint them as inherently criminal. That may seem like a cut-and-dry thesis, but over the course of just an hour and 40 minutes, 13th tackles the war on drugs, the Central Park Five, Jim Crow, Willie Horton, police shootings, mandatory minimum sentences, The Birth Of A Nation (no, not that one), and a dozen other related topics. The result is nothing less than an abbreviated history of racial inequality in America, with the prison system as the vortex at its center.

That’s a lot of ground to cover, and the film can be as exhausting, in its flood of information, as it is exhaustive. But DuVernay keeps it all chugging and churning along, propelled by the force of her montage and the sheer volume of damning, gripping material. 13th has the rat-a-tat accessibility of one of Michael Moore’s or Alex Gibney’s pop documentaries, announcing the arrival of each new decade with a lyric video (often a politically charged hip-hop anthem). But its ideas about culture and history are sophisticated enough to fill out a seminar. The first hour is an infuriating mad dash through the 20th century, stretching from the post-antebellum years all the way to the late ’90s, as DuVernay’s brain trust of talking heads lay out how Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton helped spawn the prison industrial complex. Each detour, polemical insight, and interview fragment (with everyone from poet Malkia Cyril to iconic activist Angela Davis to Newt Gingrich) inevitably feeds back into the larger point: that prisons are the new plantation, grinding up black bodies to generate profit.

13th isn’t especially interested in feigning ideological “balance.” The closest the film comes to arranging a heated debate is letting a representative from ALEC, the nonprofit organization that’s been at the forefront of prison privatization, spin his company’s indefensible position, as various big thinkers dismiss every one of his talking points. DuVernay would rather shine a spotlight on our current political climate and show how it echoes decades upon decades of policy and attitude. As in Selma, the point is made that broadcasting the ugliness of racial violence—be it lynchings, nonviolent resisters being blasted with firehouses, or recent instances of police brutality—is a powerful tool for change. There’s also a remarkable moment where DuVernay cuts soundbites of Donald Trump bragging about the “good old days” at one of his rallies to footage of African-American civilians being harassed during the civil-rights era. (Lest one think all of this is partisan propaganda, the “Super Predator” label is also addressed.)

Is there too much here for one film? 13th could have run 13 hours, as an O.J.: Made In America-style miniseries, and it would probably still seem a little out of breath. But even when stretching itself thin, this ambitious, complex take on American values never seems to be simplifying its arguments. Part of the movie’s power comes from the way it puts everything in context, drawing connections across decades and tying all its loose strands together in a way that supports one interviewee’s assertion that “systems of oppression are durable,” that they “reinvent themselves.” Besides, no more than a few minutes ever pass without some enraging illustration, such as the moment where DuVernay strings together several caught-on-tape shootings of unarmed black civilians into a kind of devastating supercut of injustice. A vital state-of-the-union address, 13th connects yesterday’s America to today’s, showing that—for as far as we’ve come—the big difference between them isn’t nearly big enough.