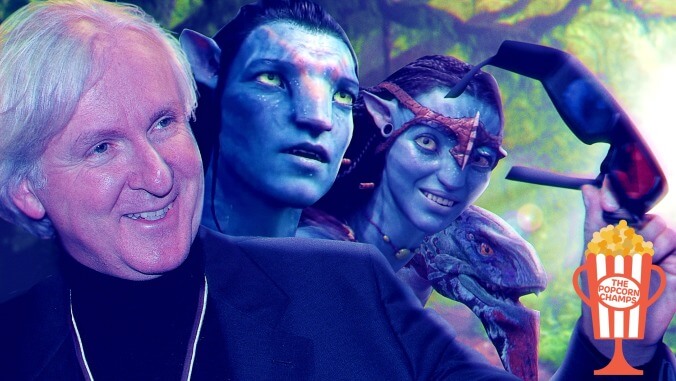

Avatar, a strange dream that became the biggest movie of all time

Image: Graphic: Karl Gustafson

It’s been more than a decade since a wholly original film was the biggest hit of its year. All our reigning blockbusters since 2009's Avatar have been sequels or adaptations or sequels to adaptations. The military biopic American Sniper, the biggest hit of 2014, could be considered an exception, but it was based on a widely read memoir, and it was about a real-life famous person. Avatar was something else: a wholly original story, with wholly original characters, written just for the screen. Movies like that simply don’t become huge hits anymore.

With that in mind, it’s possible to look at Avatar as the last relic of an era when original movies could dominate—but that’s not right, either. To find another original film that was the biggest hit of its year, you’d have to go all the way back to 1998's Saving Private Ryan, 11 years earlier. In the past 22 years, Avatar has been the only one. That means studios have been keeping the lights on by giving us familiar sights for more than two decades. And it means James Cameron’s Avatar is an aberration, a world-historic fluke.

Cameron has said that he got the idea for his 1984 breakout The Terminator from a fever dream that he had while working on Piranha II: The Spawning. While sleeping, he’d conjured the image of a gleaming robotic skeleton rising from flames. The central image of Avatar also came from a dream, one Cameron’s mother recounted to him of a 12-foot-tall blue woman. He kept that image with him for decades, and he eventually turned it into the highest-grossing movie in history.

Cameron has made sequels, and he’s liberally peppered his movies with visual echoes of other ones. But if those two stories are true, then the director’s best source for intellectual property isn’t comic books or young adult literature or even the sci-fi paperbacks that he so obviously loves. It’s the unconscious mind.

Avatar could only exist because Cameron had already made the highest-grossing movie in the history of the world. He’d started writing Avatar before he finished 1997's Titanic, and his initial plan was to make Avatar in time for a 1999 release. When he started working on it, though, he found that the special effects of the day weren’t good enough. Rather than filing the idea away and getting to work on something else, Cameron made a couple of passion-project undersea documentaries, and started helping to make the tech that he’d need to make Avatar possible. He invested millions of his own money, for instance, on developing a new 3D camera. Avatar, then, is a product of one man’s obsessive laser-focus and artistic megalomania. He wouldn’t let his idea go.

Even after Titanic did what Titanic did, 20th Century Fox was nervous about investing hundreds of millions of dollars into a movie as bugshit as Avatar. You can see why they might’ve been nervous, even with Cameron’s track record. Avatar, after all, is a Dances With Wolves riff about giant blue shamanistic aliens on a magical psychedelic forest moon and the humans who go to war against them to mine something called unobtanium. There is no easy elevator pitch for this movie. Cameron has said Fox outright passed on the film mid-development and that it wasn’t until he showed his concept art to Disney that Fox blinked and exercised its right of first refusal. Ultimately, the Fox executives found outside financing to cover half of the budget. A James Cameron vision was still a risk.

If any filmmaker other than Cameron had made Avatar, the movie would’ve been unwatchable. He was working with the same CGI as every other director in 2009, and if you hold Avatar up next to something like Michael Bay’s Transformers: Revenge Of The Fallen, the year’s No. 2 hit, the difference is stark. Cameron, once a special-effects artist himself, did everything in his power to make his movie an immersive experience. He brought in a linguist to invent a whole new language for the Na’vi, his blue aliens. His set designers came up with whole new flora and fauna for the world of Pandora, as well as whole new technology for the human invaders to use. You don’t have to know about all the extra stuff to enjoy the movie. You can just sense that people worked to make this look right—to ensure that the film would not just barrage you with two hours of herky-jerk CGI chaos.

Cameron is also a populist cornball entertainer, and that side of him is on full display throughout Avatar. The film’s hero is a blandly handsome lantern-jaw military type and its saintly and idealized natives are stock characters, echoes of the supporting cast of every white-savior myth in the trope’s history. The villains are a smarmy, sneering corporate exec and a mean, scarred-up military bastard who looks like a video-game character. Sigourney Weaver plays a Sigourney Weaver type. Michelle Rodriguez plays a Michelle Rodriguez type. Every plot development is predictable. Every character is an archetype. This is not a complaint.

Cameron speaks the language of blockbuster cinema better than any filmmaker this side of Spielberg. He knows how to manipulate you. He knows how to make you feel the thrill of adapting yourself to this alien planet, the frustration of watching your bosses destroy the world, and the righteous anger that might make you want to lead a revolution. In Avatar, Cameron casts a group of actors—Weaver, Rodriguez, Giovanni Ribisi, Stephen Lang—who know exactly what movie they’re in. The film’s broad silliness is not an accident.

Sam Worthington, the film’s lead, was a total unknown when Cameron cast him, and he’s the movie’s greatest flaw, the void at the center of everything. For one thing, he never quite manages to shed his Australian accent. Worthington also can’t hold the screen like Cameron’s other heroes, like Weaver or Schwarzenegger or DiCaprio. But I think that’s intentional on the director’s part. Worthington’s Jake Sully is a blank—an empty glass waiting to be filled. He’s the audience surrogate, so he doesn’t really need to have too much personality. He just has to feel things.

There’s something fundamentally silly about the Na’vi, the blue-skinned and cat-eyed aliens with whom Sully gradually ingratiates himself. After all, these are azure giants who use intertwined braids to fuck and to ride dragons. They’re funny. But Cameron depicts the Na’vi with total sincerity. To him, they’re not a joke. It’s a little gross that many of the people of color in the cast—Zoe Saldana, Wes Studi, CCH Pounder—are forced to put on motion-capture suits and appear on screen only as blue giants. But the director is trying to make a point here. He casts people of color as the Na’vi because you’re supposed to think of them as people of color. Avatar is a movie about, among other things, colonialism and rapacious capitalism.

Looking back through Cameron’s filmography, virtually all of his heroes are working-class people: a waitress, a power-loader operator, a drifter. He even depicts the scientists of The Abyss like they’re oil-rig workers. The villains, meanwhile, are slimy corporate types who value profit over life, or they’re the robots that these slimy corporate types accidentally empower. Avatar has its obvious and hamfisted environmentalist themes, and it’s also a dire warning of what happens when militaristic nation states and vampiric corporations work together.

The movie’s soldiers are canonically ex-military, but they’re all Americans, and Cameron layers on the imagery of occupying forces and profit-motivated wars. The destruction of the HomeTree looks an awful lot like 9/11, but the people committing the acts of terrorism are American troops. Those military forces speak of a “shock and awe campaign.” Stephen Lang’s Colonel Miles Quaritch indulges in Bush-era hawk jargon: “Our only line of security lies in preemptive attack. We will fight terror with terror.” The big companies and the soldiers backing them up are the unambiguous villains, and only a few of those soldiers have enough empathy to figure out that what they’re doing is wrong. By the end, nature itself declares war on these invaders, as Pandora’s hammerhead rhinos and tiger-bug monsters join the fight.

Avatar is an unapologetic work of pastiche, from the prog-album-cover vistas of the Pandoran forest to the Miyazaki-style worship of nature. Certain influences are all too obvious. The moment where the Na’vi tribes gather is pure Lord Of The Rings, while the forest battles echo the Endor scenes from Return Of The Jedi. Sigourney Weaver’s presence only underlines how similar the military characters are to the ones that the director had already used in Aliens. The movie’s hacky parts—the clumsy narration, the stilted dialogue, the tree-worship bits where the hordes of Na’vi look like audience members in a Guitar Hero game—play into that sense of pastiche. For that matter, so does the white-savior stuff; the film exists in a long line of movies about white guys who immediately become the most awesome people in the societies that adopt them. Those are the reasons why Avatar is embarrassing, why the movie is such an easy snark target.

And yet Avatar fucking stomps. The movie is nearly three hours long, but it moves. Within 15 minutes, Sully is in the Na’vi body. Before the first hour is over, he’s riding banshees. Things slow down for the scenes about spiritual interconnection with trees, but even those don’t derail the narrative momentum. The film’s final battle is a long, elaborate masterpiece of action cinema. It’s fast and mean and exciting, and it’s about a million times more coherent than the substantively similar CGI giant-robot explosion-fests that Michael Bay was making at the same time.

Avatar also looks amazing. 3D movies started coming back before it arrived, but the film supercharged the trend. To watch Avatar at home is to behold a distant echo of the stoner phantasmagoria that Cameron put together for the theatrical release. Going to see the movie felt like an event. My daughter was born in 2009, so that’s the year I suddenly became one of those people who only makes it out to the theater three or four times a year. Clearing out the time necessary to see the movie with my wife felt like a big deal, but it also felt totally necessary. I walked out of that theater numb with adrenal fatigue. After months of no movies, Cameron had grabbed me by the back of the neck and heaved me into one.

Avatar certainly owed a certain amount of its huge box-office haul to the novelty of the immersive 3D experience. It’s tempting, I think, to look at the movie as something like a 21st-century version of Cinerama Holiday, the new-filmmaking-technology demonstration that became 1955's highest-grossing movie. But Avatar succeeds on a level beyond the sensational. It’s an elemental story, told well. The whole visual experience mattered to its success, but so did that story. Shortly afterward, other studios rushed their own 3D experiments into production. A few months into 2010, Disney had a monster blockbuster with Tim Burton’s near-unwatchable Alice In Wonderland adaptation, and that success came down almost entirely to the way the Mouse House pushed the whole immersive-3D-world story. Alice In Wonderland became the second-biggest hit of 2010, and that only happened because of Avatar.

It’s wild to consider just how much money Avatar made in its day. After a big opening weekend, the movie barely dropped in the weeks that followed. It made a billion dollars within three weeks, and it reached two billion, a number that no movie had ever touched, in a little more than a month. Avatar did ridiculous numbers around the globe, and it reigned for more than a decade as the highest-grossing film in history, dethroning Cameron’s own Titanic. Inflated prices for 3D and IMAX screenings helped juice Avatar’s box office, but a whole lot of other movies have had those 3D prices, too, and they haven’t beat it.

In 2019, something finally bested Avatar. Avengers: Endgame—another movie where Zoe Saldana plays an alien with a florescent skin color—skated past the all-time box office record. But it didn’t hold that record for long. Last month, with Chinese theatrical business once again booming, Disney re-released Avatar in 3D in China. That reissue brought in another $21 million, and now Avatar once again reigns as the highest-grossing film in the history of the global box office. Since Disney now owns both Endgame and Avatar, this amounts to one corporation big-dogging itself, sort of like that Kanye West/50 Cent release date battle when both of them were signed to Universal. Still, it’s a sign that Avatar has never quite disappeared. People are still willing to pay for that experience.

Avatar was a wild success on a lot of levels, but it was a failure on another: It didn’t change the world. A couple of weeks ago, former presidential candidate Marianne Williamson interviewed Cameron on her podcast, and they spent a lot of time discussing the movie’s spiritual underpinnings and environmental messaging. Toward the end of the podcast, Cameron laughs sadly and says, “It didn’t work.” Hundreds of millions of people had seen his film, and it had done nothing to slow down the cancer of corporate greed. Cameron knows that this was not a realistic goal: “Not that any film can do anything on its own. It has to be a kind of slow evolution of the zeitgeist.” But Cameron tried. Avatar is the product of someone who sincerely wanted to speed up that evolution.

In recent years, it’s become popular to talk about Avatar as the disappearing blockbuster—the film that made a ton of money and then vanished completely from culture. That’s not entirely accurate. The Chinese reissue showed that it’s still a draw. There’s a whole Disney World mini-park dedicated to replicating that Avatar ambience, with the giant floating mountains and the people walking around in mech suits and everything. But in sacrificing characters for spectacle and messaging and world-building—and in not having the advantage of whole comic-book cosmologies to draw on—Avatar hasn’t kept its hold on people’s imaginations in the ways that some other blockbusters have done. That might change, though. In a year and a half, we will supposedly see the first of four planned sequels, all directed by Cameron. I’ve heard people asking why this is happening—who asked for more Avatar? But the last two sequels that James Cameron made were Aliens and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. The man knows what he’s doing. Let him cook.

The runner-up: Pete Docter’s Up, 2009's No. 5 movie, might represent the moment that Pixar stopped making movies for kids and started making movies for emotional adults that kids could also watch. The early montage of a married couple’s relationship over the years reduced grown people to blubbering snot-piles, and Up deserves respect for that alone. But everything that follows is great, too—a fun, absurdist adventure with a never-ending supply of jokes. Up has talking dogs, and it also has total respect for its characters. It’s got range.

Next time: Toy Story 3—one of the all-time great animated films, and maybe the best thing that Pixar has ever done—uses generationally beloved characters as vehicles for a whole lot of people to feel a whole lot of things.