Bad Religion and Douglas Adams: 9 pop-culture works that launched teenage rebellion

This week’s question comes from returning AVQ&A participant XIO666:

“Which piece of pop-culture marked the start of your teenage rebellion phase, defined as the first active attempt to redefine oneself independently of parental influence and social programming? For me it was Stranger Than Fiction by Bad Religion. Before that, I was the goody-two-shoes son and listened to the most bland music imaginable. I did not have many friends and this whole thing just wasn’t working for me. Then I accidentally picked up the cassette at 14 and from the very first song, “Incomplete,” something in my mind just changed instantly. Within a year I was wearing Ministry and Skinny Puppy T-shirts and going to mosh pits. I still had as few friends as before, but at least now it was on my own terms.”

As a nerdy, repressed teenager (who’s grown, obviously, into a nerdy and happily repressed man), my rebellions were quiet, personal, and mostly in my head. But I still remember the first time I read the opening pages of Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, and had my worldview permanently shifted by the idea that you could watch the world get blown up by pigheadedness and stupidity, and still crack jokes about it as the pieces went flying. Up until that moment—in 7th grade, I think—I had never actually understood that comedy was an antidote to fear, that a healthy sense of ironic detachment could drain away the sense of earth-shattering importance that had made pretty much every moment of my life up until then such a nerve-wracking, over-achievement-prone nightmare. (Or, to put it more pithily: Don’t Panic.) Obviously, I then immediately took my newfound revelation way too far, transforming into a pretty classic version of the sarcastic teenage shithead, but hey, what else is a “rebellious” teen supposed to do? [William Hughes]

It was generally pretty hard to rebel against my parents—except for their weird disdain for Dungeons & Dragons, they let me and my siblings listen to and watch what we want. But, like so many other suburban ne’er-do-wells who bought Dookie and found themselves looking for more, I got really into Lookout! Records and third-wave ska, something my parents had not anticipated at all. And like any good student of the form, I obsessed over Operation Ivy’s self-titled omnibus collection in particular, drawing its logo everywhere and listening to “Sound System” repeatedly. Being in my family meant you inherited a lot of specific tastes, but this was definitely the first place I began etching out my own. [Clayton Purdom]

Growing up, my dad liked and so much that they were practically required viewing, and I’m barely older than so I must’ve picked that up from my brothers, but the first thing I remember liking so much that I couldn’t have cared less if anyone else liked it was Space Ghost Coast To Coast. I had somehow seen some original Space Ghost cartoons as a kid, so it just blew my mind when I turned on Cartoon Network one late night and saw the old sci-fi superhero doing absurd comedy. It seemed so cool and so smart, and while the other middle school kids were getting into MTV or whatever, I was watching Adult Swim and deciding that I liked weirdo cartoons a lot more than I liked fitting in with other kids. Today, I can probably count on one hand the people I’ve met who know the difference between a shark on whiskey and a shark on beer, and that’s exactly the way I like it. [Sam Barsanti]

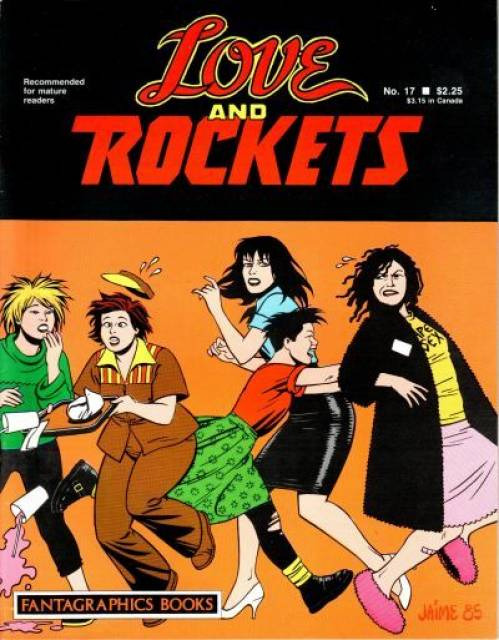

I was a wannabe punk for the longest time, trapped on a Midwestern campus in the midst of the first Bush years, miserably surrounded by one of the largest Greek systems in the U.S. Other than Paul Westerberg and multiple viewings of Repo Man, who was going to show me the way out of sorority row hell? I found my two-dimensional punk role models on the pages of Love & Rockets, the groundbreaking comic by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. I loved Beto’s trips to the mystical Gabriel García Márquez-inspired village of Palomar, but Jaime’s Locas stories cemented my youthful rebellion. His half of the comics followed young punks Hopey and Maggie around Oxnard, California, continually broke, going to dive bars and crashing parties with pals like Penny Century and Mexico-obsessed Izzy. The characterizations were like a punk-rock Archie comics, yet the Locas’ wisecracks and antics were as fully fleshed out as any of my alterna-minded friends. I soon adopted a wardrobe of giant overcoats and vintage housedresses from Amvets, Converse high tops and black boots, and even used a copy of the comic as a model so that my haircut would mimic Hopey’s scarecrow style. The day I got a letter published in the L&R letters column was one of the happiest of my entire life. Maggie, Hopey, and I have longer hair now, but I like to think we still hang on to the punk credos of our formative years. [Gwen Ihnat]

I had the opposite problem from Clayton—it wasn’t that my parents let me watch, read, and listen to anything I wanted (far from it—I remember my mom one time in the car, rebuking my turning up Jimi Hendrix on the radio with the stern admonition, “Alex! Jimi Hendrix did drugs”), so much as my concept of rebellion was so lukewarm as to be practically complimentary. I distinctly recall bravely sneaking out after they went to sleep one night so that I could… go for a walk in the park a block over when it wasn’t crowded. Hence, my rebellion mostly came in the form of intellectual gestures against their tastes. And nothing lit my world on fire in that regard so much as the first time I saw Hal Hartley’s Simple Men. Here was a film clearly made on a low budget, with little concern for the kind of sanitized polish striven for by most cinema I had seen until then, where people looked different, spoke different, and did things differently than any other movie I had seen before. (Or since, in most cases—Hartley is still such an idiosyncratic filmmaker that he inspires nothing like the legions of imitators spawned by a Darren Aronofsky or a Wes Anderson.) I subsequently devoured his entire oeuvre—Trust, The Unbelievable Truth, Amateur, Henry Fool, and more as they came—and those films became something very much like a manifesto for my adolescent awakening to the wider world of underground art and culture waiting just beyond the fringes of my normal suburban access to entertainment. It’s best captured in the above moment: when characters cast everything aside for a moment, and just fucking dance to Sonic Youth in the most awkwardly awesome way possible. [Alex McLevy]

Growing up, music was Jason Mraz skatting in my mom’s car, “Sweet Home Alabama” at barbecues, and Jesse McCartney, because the Disney Channel told me to love him. As a cripplingly anxious teenager struggling find myself in the homogeneity of my suburban high school, it felt essential to like the music that played on the radio. In true nerd form, before every school dance I’d study up on the iTunes Top 100 so I’d know the songs well enough to anticipate what to do with my arms when they inevitably came on. But in my sophomore year, my neighbor introduced me to Tune-Yards, and their music—between Merrill Garbus’ husky vocals and their experimentation with sound and discordance—was unlike anything I’d ever heard. I think that was the appeal. It sparked an active search for unusual and interesting music, and I fast fit myself into a new, chunky sweater and hipster glasses-wearing mold. It was still a mold, mind, but it made me feel like an individual in my high school. [Maggie Donahue]

My older brother was the transgressor of the two of us. He was the one who tested the acceptable limits for movies, music, and general behavior. This was tough enough in the swirling chaos of our household after my mom died. And besides, I still filtered all of my teenage pop culture tastes through him for approval anyway, so any statement I was making would simply be an anemic, sputtering ember to the fires he already started. If I was going to rebel, it would have to be in the opposite direction. I managed to baffle both my brother and my father by being heavily into video games. It was a hobby that neither had any interest in, and they couldn’t understand mine. Once I preemptively worked up a compact manifesto in defense of Final Fantasy II in my head, preparing for the inevitable disdainful question from my brother about why I enjoyed it so much. When he did, I rattled off my prepared speech with robotic persistence until he told me to shut up. He hasn’t asked me about games since, and I still think Final Fantasy II has good graphics and neat characters. [Nick Wanserski]

I’ll never forget the morning in eighth grade I got on the bus to go to school before dawn, like I always did, and sat next to my friend Wes, like I always did. Wes and I had gone to elementary school together, where we had jointly discovered entry-level teenage rebellion in the form of Green Day and Nirvana; by the time we hit junior high, however, Wes had started sticking his hair up into a mohawk with Elmer’s glue and getting into serious punk rock the likes of which was not available at the local Media Play. That’s what led to Wes handing me his Discman, saying, “check this out,” pressing play on Bikini Kill’s The Singles, and changing my life forever. I had no idea that music this raw and confrontational existed, let alone was being made by women who were confident and street-smart and wise in the ways of a world that still terrified and confused me at the age of 13. It blew my mind. It wasn’t long after that that I made my own Bikini Kill T-shirt by drawing with a Sharpie on a white shirt smuggled from my dad’s dresser drawer, a rough sketch of the record player on the cover of The Singles on the front and lyrics written in neat, girlish cursive on the back: “We’re not going to prove nothing, nothing / Sitting around, watching each other starve.” That’s from a song called “I Like Fucking,” which I always tried to play off as no big deal when I was hanging out behind the cafeteria smoking with the punk kids, even though I blushed every time I said that word aloud. [Katie Rife]

The advent of the remote control was a TV milestone, forever freeing viewers from the tyranny of the dial and paving the way for an age when the entire history of visual media is available (pending flimsy licensing agreements) at the push of the button. The personal liberty of this specific viewer can be traced to a single button: “Previous channel,” as found on the remote to the Philco set my family kept in our basement during the late-’90s. At the slightest sound of a parental intrusion, the button allowed me to flip away from verboten programming like MTV or The Simpsons to the safe harbors of Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network. For this reason, I’ll always have those channel numbers memorized, the lineup of a Clinton-era cable package forever crowding vital information out of my memory banks. I no longer know how to do calculus, but I do remember that Nick was channel 27—which is its own form of teenage rebellion, I suppose. [Erik Adams]

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.