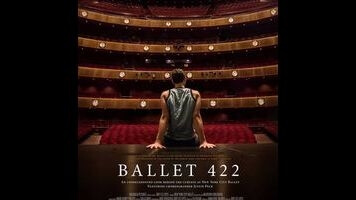

“Art isn’t easy,” wrote Stephen Sondheim, and in Jody Lee Lipes’ bleak beauty of a documentary, the act of creation is a resolutely joyless one—a tedious grind with little lasting reward. The film’s primary subject is 25-year-old Justin Peck, who works as a low-level corps dancer for the George Balanchine-founded New York City Ballet. Initially, it seems as if the film might just follow him through the ups and downs of his relatively anonymous profession. But an on-screen title quickly informs that Peck is also an aspiring choreographer of note who has been commissioned by the NYCB to create the company’s 422nd production. It’s an original piece titled Paz De La Jolla with three principals and several backup dancers, set to Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu’s Sinfonietta La Jolla, and Peck has only two months to get it in shape.

It’s easy to imagine any number of disasters befalling the production, but what’s interesting is how the process remains mostly drama-free. There are occasional hints that people look down on Peck for his youth (the orchestra leader assumes a skeptical, paternalistic tone when Peck asks to speak to the pit musicians). And there are a few moments when the choreographer’s inarticulateness (very mumblecore in its way) seems like a passive-aggressive ploy to get what he wants from the company’s ever-inquiring behind-the-scenes team. Mostly, though, things go off without a hitch, which might lead prospective viewers to wonder how there can be a movie when very little of outward consequence happens.

The tension of Ballet 422 is supplied mainly by Lipes’ consistently inventive and probing visuals (imposing long shots looking down the NYCB facility’s hallways; a solo rehearsal dance seen mostly through a recording iPhone) and by what he chooses to elide. No one ever speaks directly to camera and all the action is captured as it happens. In this way, Lipes appears to be following in the footsteps of direct-cinema pioneers like D.A. Pennebaker and Frederick Wiseman, though to very grim ends. Paz De La Jolla is never shown in full, so there’s little sense of the movie building to a triumphant climax. Premiere night is, in its own way, as ordinary and humdrum an experience as any of the lengthy rehearsal periods or offstage bull sessions with lighting and costume designers. (Take a bow, then get back to work.) And that title is no accident—Peck’s project, as Lipes presents it, is just another number in a perpetual cycle, ultimately more of a statistic than it is a statement.

It’s rare that movies capture the cumulative toil of the creative process as profoundly as Ballet 422, and the lack of any end-result elation forces some tough, resonant questions with no easy answers. Is Peck’s effort worth it? Or, perhaps more pointedly, is his effort all there is?

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.