Banned Book Club gives deeply personal context to government censorship and violence

It’s hard to imagine a world where Banned Book Club could be more relevant than it is right now. If it’s not clear from the title, the graphic novel revolves around a group of young people who meet to read and discuss books banned by their government. It’s set in South Korea in the early 1980s, a time that most Americans are entirely ignorant of but may find upsettingly familiar. Not so far removed from the Korean war and under the weight of a military regime that used censorship and violence to maintain control, a group of students gather in secret to read titles like Pedagogy of the Oppressed and The Feminine Mystique.

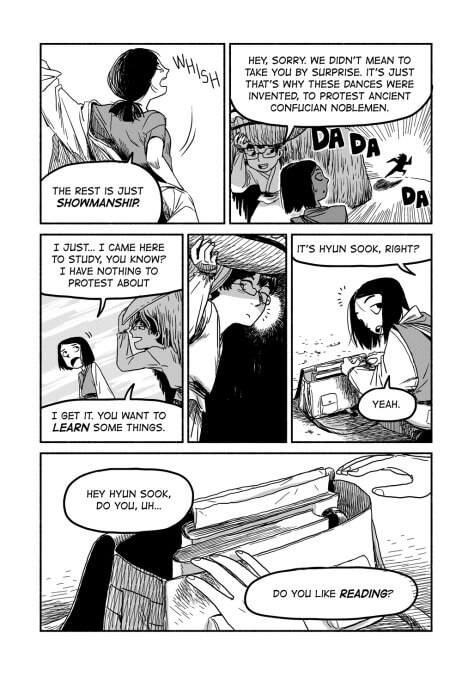

At the center of the story is Kim, a young woman caught between the needs of her parents (and their small restaurant) and her desire for more education and opportunity. As she meets and befriends the rest of the students in the titular club, she realizes that not only is there a whole world beyond what she knows, but also that her government has been lying to her—and everyone else—without consequence. Several of Kim’s friends are targeted by the government and subjected to surveillance, arrest, and worse.

Even if it were just based on the history of the Fifth Republic and the abuses meted out on Korean people, Banned Book Club would be a powerful and illuminating read. What makes the book even more potent is its basis in the real life of writer Kim Hyun Sook and her friends. Kim worked with her husband Ryan Estrada on the story and script, relying not just on her memory but also extensive research and interviews. Estrada’s name may be familiar to fans of his Poorcraft series from Iron Circus, his self-published Broken Telephone comic, or his excellent guides on how to read Korean that have been floating around online for a while.

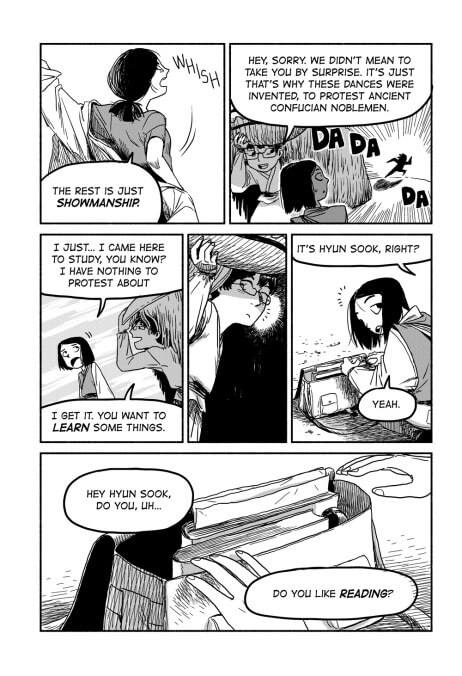

Kim’s very real understanding of the dangers and threats from this time period, paired with Estrada’s expertise in pacing and comedic beats, have resulted in something special, and Ko Hyung-Ju’s art brings it to vibrant life. The book has a lot in common with manga and feels far closer to that than traditional American comics; it’s printed in grayscale and characters are drawn relatively simple, with some features slightly exaggerated. Hyun Sook and her friends are young and enthusiastic, and the expressions Hyung-Ju depicts show how, even in the face of all-too-prevalent danger, they maintain idealistic verve. It’s hard not to feel energized and encouraged by the book’s insistence that the world must bend towards justice, and it ends on a realistic but hopeful note by providing context for current South Korean politics.

Banned Book Club joins a growing category of books that tackle not just history, but the insight it can offer to current events. It often seems like people are using the term “unprecedented” to refer to what’s been happening in the U.S., politically speaking; but there is a lot of precedent to be had, if readers go looking. Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes was published this month as well, and both books offer powerful insight into the relationship between censorship and violence, as well as the threat that a lack of information poses to a people.