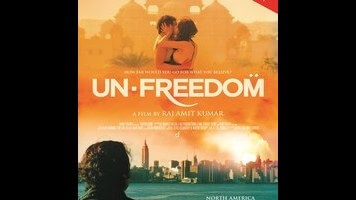

Banned in India, Unfreedom hasn’t much more to offer than provocation

It’s no surprise that the Indian drama Unfreedom has been the subject of major controversy in its native land. Raj Amit Kumar’s film, which was banned by the country’s national censor board, is an intentional act of cultural and political provocation, and goes about its task as relentlessly as possible.

Unfreedom has a double-tracked narrative, intercutting rather gracelessly between two plots without ever joining them. This lack of unity is not a mistake: The point seems to be that we’re watching two superficially different versions of the same story, with human beings torn apart, figuratively and then literally, by deep-rooted prejudices and religious fundamentalism.

In New York City, Fareed (Victor Banerjee), a respected Muslim intellectual, prepares to give an address about tolerance and understanding, unaware that he’s being stalked by kidnappers. In Delhi, radical painter and LGBT activist Sakhi (Bhavani Lee) makes fiery speeches while her sometime-lover Leela (Preeti Gupta) plans to propose going steady as a way of escaping her own prearranged marriage. Kumar labors to make sure the parallels are clear: Both Fareed and Sakhi are paradigmatic figures who spout progressive rhetoric in public; both are admired and loathed for their courage; both are abducted and held captive for their troubles.

The difference is that where Fareed is taken by extremists who mean to make a videotaped example of him to the world—and are prepared to hurt him horribly to make that happen—Sakhi is spirited away at gunpoint by a woman who wants to possess her romantically (so much so that she shoots Sakhi’s boyfriend to get him out of the way). So while Fareed is being tortured with various sharp and/or blunt instruments, Sakhi and Leela are quietly ravishing each other in the desert. Brutal violence and consensual sex are rendered with equal explicitness, as if Kumar is daring his viewers—perhaps especially his compatriots—to feel judged by the juxtaposition.

In both stories, we’re reminded constantly of the courage of certain characters, which seems like Kumar’s way of congratulating himself for skewering certain sacred cows. His film about heroic outliers in a repressive society may be at least partially intended as a self-portrait (it opens with Sakhi reverentially sketching her own nude image). Admirers of this film could claim that it doesn’t “sanitize” its subject matter, but there’s another side to that coin: By playing up the gore of Fareed’s ordeal, Kumar is engaging in a high-toned form of exploitation filmmaking (a link that gets cinched in that story’s preposterous climax). Unfreedom is undeniably a passionate effort, and the furor over its existence may ultimately validate its thesis. But it’s not enough to just jab at hot-button topics. You need to do so with a deft hand. And as far as filmmaking goes, Kumar is all thumbs.