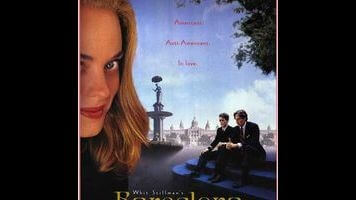

Whit Stillman tends to be cagey about when his movies take place. His 1990 debut, Metropolitan, claims to be set “not so long ago,” which is most likely sometime around 1970. Likewise, Barcelona, which joins the Criterion collection this week (both singly and as part of a Stillman box set with Metropolitan and The Last Days Of Disco), places the action, such as it is, during “the last decade of the Cold War.” That sounds flatly descriptive today, but it registered as a wry joke at the time of the film’s 1994 release, when the end of the Cold War was no more distant a memory than “Blurred Lines” and Frozen are now. All the same, Stillman was very much in earnest. The world had changed dramatically, almost overnight, and Barcelona—one of the few comedies ever made that’s explicitly about anti-American sentiments abroad (the only other example that springs to mind is Billy Wilder’s One, Two, Three)—suddenly looked like a musty period piece. While that might have seemed disastrous to some filmmakers, Stillman is as much an anthropologist and sociologist as he is an artist. For him, instant archaism was a blessing, not a curse.

In any case, his characters always seem to inhabit a hilariously verbose world of their own. Barcelona pairs Metropolitan’s two funniest actors, Taylor Nichols and Chris Eigeman, as cousins rooming together in Spain circa the late ’80s. (At one point, the film briefly addresses a USO bombing that kills a U.S. sailor; in real life, that happened on December 27, 1987.) Ted (Nichols), a stammering, bookish wallflower, works as a foreign-sales rep for IHSMOCO, the Illinois High-Speed Motor Corporation, and spends his off hours gazing wistfully at the beautiful women who work at Fira De Barcelona, the world’s fourth-largest trade fair. Ted’s game gets an involuntary upgrade via the unannounced arrival of cousin Fred (Eigeman), a brash, fervently patriotic Navy officer who’s been dispatched to Barcelona as an advance man for the fleet. The odd-couple shenanigans kick off with Fred falsely informing women at a disco that Ted is into sadomasochism, and before long both cousins are entangled in ludicrous romantic and/or sexual liaisons.

Like all of Stillman’s films (with the exception of his forthcoming Love & Friendship, adapted from a Jane Austen novella), Barcelona is more a collection of amusing anecdotes than a narrative. Some of these are essentially random, as when Fred worries aloud that he’s been shaving in the wrong direction his whole life (and might teach a future son to do the same), or when Ted explains to a bewildered Fred what the bluntly obvious material that sits atop a work’s subtext is called (“the text”). But much of the film’s comedy is organized around Fred’s growing dismay and irritation at the negative reaction his Navy uniform inspires. A pompous Spanish journalist, Ramon (Pep Munné), serves as a villain of sorts, accusing the U.S. of false-flag operations even as he seduces the same women Ted and Fred are pursuing; the sputtering outrage exhibited by Fred (and to a lesser extent by Ted) is expertly calibrated for laughs, but it’s easy to discern an underlying sincere resentment. What might have been unpleasantly didactic in less skillful hands comes off goofy and charming here.

What makes Barcelona the least of the three films in Criterion’s new box set (a relative criticism; they’re all terrific) is its treatment of the female characters. One major problem is that Stillman, for some reason, chose not to cast Spanish actresses as the Spanish women—Fred’s primary love interest, Marta, is played by Mira Sorvino (who was barely known at the time; she’d win the Oscar for Mighty Aphrodite a year later), while English-born, Australian-raised actress Tushka Bergen likewise struggles with a Spanish accent as Ted’s paramour, Montserrat. Even had these roles been cast more authentically, though, they’d still be fundamentally ornamental. Ted and Fred are rich, detailed individuals; Barcelona’s women are merely trophies (one of whom almost literally gets passed from one cousin to the other), and Stillman’s efforts to dissect that in the dialogue, via Ted’s decision to start pursuing only plain or even homely women, doesn’t change the lopsided nature of many scenes. To his credit, though, Stillman appears to have recognized this, as every film he’s made since, including his new one, is decidedly female-centric. (Last Days Of Disco is arguably a coed ensemble, but it’s Kate Beckinsale and Chloë Sevigny whom people remember.) Lapses are easy to forgive when you’ve already seen the artist course-correct.