Bare-knuckle drama Donnybrook is pretentious and gratuitous—an unfortunate one-two

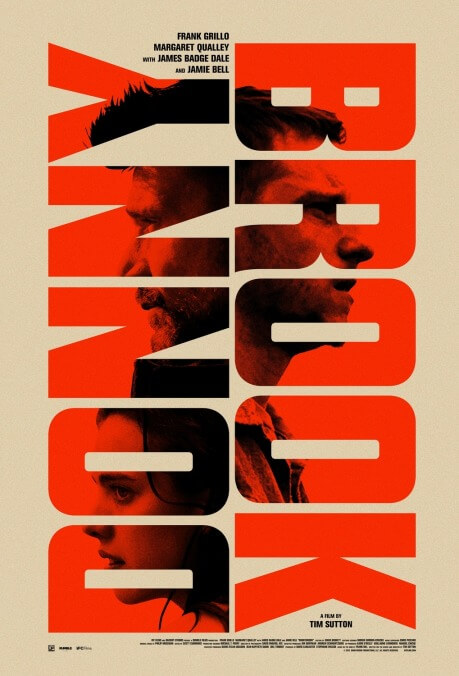

Populated by characters with names like Jarhead Earl and Chainsaw Angus, Frank Bill’s debut novel, Donnybrook, doesn’t necessarily aim to be perceived as naturalism, even if the meth-ravaged parts of Kentucky and Indiana where it takes place are very much based in reality. All the same, Tim Sutton’s screen adaptation frequently blunders over the line separating evocative exaggeration from noxious bullshit. Early on, for example, it’s established that a young woman named Delia (Margaret Qualley, from The Leftovers) is completely under the thumb of her psychopathic brother, the aforementioned Chainsaw Angus (Frank Grillo). It’s a weirdly incestuous relationship, which Donnybrook needlessly underlines by having Angus instruct Delia to kill a man by having sex with him and blowing his head off at the precise moment of his orgasm. Sutton chooses to augment this preposterous display by having diegetic opera music play tinnily in the background—a hilariously pretentious touch that pushes the scene into parody. Which might even have been fine, were Donnybrook not so grimly self-serious in most other respects.

“World’s changed,” a minor character portentously declares in the film’s opening scene. “Only thing worth livin’ for is vice and indulgence.” Jarhead Earl (Jamie Bell), however, yearns to provide his sick wife and two children with something more. To that end, he steals $1,000 and heads for the Donnybrook, a winner-take-all bare-knuckle brawl involving what looks like roughly 20 people in a single big cage. (The purse is said to be $100K, so apparently spectators are paying through the nose.) Unfortunately, he’s involved in an ill-defined feud with Angus, who beats the crap out of him early on—not a great sign for Earl’s future, given that he’s staked everything on his ability to out-pummel people. Delia, meanwhile, finally makes an attempt to escape Angus’ clutches, though she fails to make sure that the bullet she fires actually kills him. (Spoiler alert: It doesn’t.) And both men are being tracked by a corrupt deputy sheriff (James Badge Dale) who clearly has more pressing matters than law enforcement on his mind. Most of these narrative strands converge at the Donnybrook.

In general, narrative doesn’t seem to be Sutton’s strong suit. His best film to date, Memphis, avoids it almost entirely, serving up seemingly random (yet cumulatively affecting) moments of shambling lyricism. Dark Night likewise functions as a tone poem, but makes the mistake of applying that aesthetic to the 2012 Aurora multiplex shooting, which comes across as exploitative rather than cathartic. Here, Sutton is working with actual characters, played by professional actors, and his instinct is to flatten them as much as possible. Angus, in particular, demands the demonic charisma that, say, Javier Bardem brought to Anton Chigurh; Grillo plays him as a monotonously lethal husk, which may be intended to say something about American masculinity but instead creates the impression of a bargain-bin Terminator knockoff. Bell, looking like an older, burned-out version of the kid he played in David Gordon Green’s Undertow, finds a few interesting shadings in Jarhead Earl, especially when tenderly interacting with the character’s son (Alexander Washburn). But he also has to carry the weight of Donnybrook’s sentimental ideas about how the American dream has gone sour for “folks like us,” as Earl puts it in the movie’s final shot. When your protagonist is aware of who he represents, and says as much aloud, you’re flirting with being pompous. Never the best strategy, but it’s especially ill-advised to combine such platitudes with gratuitous mayhem.