Basic Instinct’s Joe Eszterhas on that famous interrogation scene, and the film’s lasting impact

The famed screenwriter talks about the relationships that inspired his characters, and the controversies that surrounded the film

Almost every aspect of neo-noir thriller Basic Instinct seemed to stir up controversy when the film arrived in theaters 30 years ago this month, including the record-setting price for screenwriter Joe Eszterhas’ spec script, Sharon Stone’s infamous interrogation scene, and the last-minute cuts made by director Paul Verhoeven to avoid an NC-17 rating.

Perhaps in part because of those numerous scrapes and scandals, the film retains a remarkably hard-edged allure. Basic Instinct tells the story of self-destructive San Francisco homicide detective Nick Curran (Michael Douglas), whose investigation of a gruesome case leads him to the doorstep (and eventually, bedroom) of brilliant but devious and possibly homicidal crime novelist, Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone).

The film’s explicit sexuality and violence attracted ticket sales even as it provoked considerable debate. Basic Instinct prompted impassioned protests before and after its release regarding Hollywood depictions of gay and lesbian characters in film, pitting activists against feminist social critics like Camille Paglia, who defended the movie.

The fourth highest-grossing film of 1992, Basic Instinct was also a massive global hit, pulling in $353 million worldwide. It has remained popular, and that police station interrogation scene (“What are you going to do, charge me with smoking?”) been has become an unforgettable part of the cultural firmament.

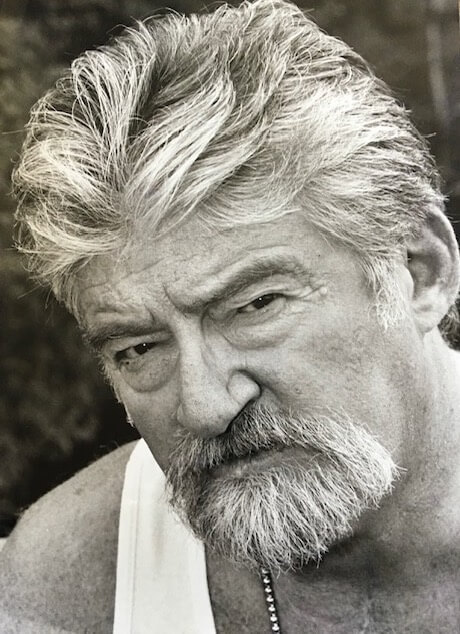

These days, Eszterhas, now 78, is living happily in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, where he’s working on a novel, Refugee, about the immigrant experience. He spoke recently with The A.V. Club in a wide-ranging conversation about the legacy of Basic Instinct.

The A.V. Club: The script for Basic Instinct sold in June 1990, and you wrote it after you bolted from CAA, following your famous letter to Michael Ovitz about the agency exec’s bullying and extortion, right?

Joe Eszterhas: Yes. I’d left CAA, and done another piece called Sacred Cows. And that’s when I decided to do the thriller. One of the reasons why some people thought that everyone in town bid on it, and why the price went up stratospherically, was that there were many people in town who had either experienced or heard about Michael’s tactics holding onto clients, and some people thought that people wanted to send him a message. I’d heard from Bernie Brillstein, for example, who was a very strong producer at the time, that those exact same words were used to him—“I’ve got soldiers who will go up and down Wilshire Boulevard and put you into the ground”—so this was obviously a tactic. And I also got letters from people like Mark Harmon, who detailed that the same kind of thing had been done to him. So my agents at least thought that people wanted to send a real signal that this kind of behavior wasn’t acceptable. Certainly agents tried to strong-arm people, but never from what I’d heard and the reaction I got, quite this way.

AVC: You wrote Basic Instinct in a sprint, finishing the script in 13 days. But how long did the ideas for the screenplay percolate, and was that period of gestation typical for your writing process at the time?

JE: It always varies, but that particular one the two people that came together in my head. One was a policeman who was a friend of mine when I was a reporter at the Plain Dealer, and another was a woman I had a relationship with who was 10 years older than I was. Many years went by, and I really didn’t ever think that I would use these two people as models, and then one day I was thinking about doing another thriller—I had done Jagged Edge and I wanted to do something different. And I’ve always been fascinated with homicidal impulse thrill-killing, and that’s the quality I saw my cop friend have. He was involved in three shootings, and in my own personal judgement he liked it too much. Now, having said that, he was also a very charming, charismatic guy. But I saw a dark side.

And in terms of the Catherine character, I really enjoyed the company of this woman that I was with—she was smart, really well-read, really manipulative, and I admired all of those qualities. So it came together in the moment of wanting to do another thriller, a psychological thriller. I didn’t really view this as an erotic thriller when I wrote it. My friend Paul [Verhoeven] had a lot to do with making it that. But certainly the sexual aspect was part of the manipulation. I thought this woman was kind of omnisexual and used sex in diabolical but very enjoyable ways, and I was a very young man so I was impressed. [Laughs.]

AVC: There was a period in the late 1980s through the mid-’90s where screenwriters became the story themselves. Tremendous attention was paid to spec script sales. Film fans would hear about these scripts, and suddenly they were paying attention to Joe Eszterhas or Shane Black as a brand.

JE: You’re absolutely right, and I’ll tell you an amusing story. Shortly after news of the sale, like 10 days later, my wife and I and our two little kids went to Florida on a previously planned vacation, and one day I get a call from CBS saying they wanted to do an interview. We weren’t very specific about the interview, so one day we’re out on the beach, we’re in Longboat Key with the kids, I’m trying to teach them how to fly kites. Suddenly I look up and there’s a helicopter coming toward the beach that says CBS News. And at that moment I turned to my first wife and I said, “Our lives have changed, no doubt.” Here comes the chopper, it lands on the beach, they start running toward me, and we do an interview that winds up leading the CBS News that night. And I said, “Come on, I’m a writer!” [Laughs.] It gave me a terrific amount of pleasure because screenwriters had always been viewed as the bottom of the totem pole. I think every screenwriter probably felt that. I didn’t feel that very much after the Basic sale, and after all the headlines.

AVC: That attention isn’t something many writers are comfortable with.

JE: It turned me into a public figure, and I never wanted that. I never viewed myself as a spokesman, I just wanted to be a writer. But in the course of writing screenplays I got fucked around with a lot, and I’m not good with that. I’m Hungarian. You have to remember that in 1956 the Hungarians staged such a revolution that teenage kids went up against tanks with Molotov cocktails in their hands. I’d come from that Hungarian tradition, and things that happened brought that out in me. One of the reasons I came back to Ohio and my hometown, besides the fact that I’d fallen in love and the woman I’d fallen in love with was also an Ohioan, was that I wanted to write and I didn’t want all the rest of it. Best decision I ever made—we had four little kids and raised them here, and raised them well, I think. Parenting is a high-wire act and we never fell off the wire. We’re still here, and I’m happy.

AVC: With the benefit of hindsight, do you think being in the news as one of the most highly paid screenwriters in Hollywood impacted the types of stories you either wanted or needed to tell?

JE: It’s a good question. The phone was going off too much. I had a publicist, and had to have that for self-defense, but then it got on my nerves with all the stuff that was going on. I liked writing different kinds of things. But I was going through a brutal divorce and my life was upside down, and truthfully, on any kind of human level, it’s difficult to turn $4 million down. And that’s what they wanted from me. That certainly played a part.

Basic sort of sucked the air out of [things] in all kinds of ways. One of the reasons my first marriage blew up was because I was the guy who wrote Basic Instinct, and I can’t tell you the number of women who came up to me and said variations of, “Okay, you can talk the talk, but can you really walk the walk?” Well, I had to prove to myself that I could walk the walk to start with, but it had all kinds of nasty results [Laughs.] I certainly wasn’t a saint.

AVC: Basic Instinct is a “cat-and-cat” story, in that Nick and Catherine are both predators in their own way, and have an awareness of their effects on other people.

JE: You know, what you said is exactly what Paul and I had an issue about over the script, before he finally went back and shot the original first draft. He said, “I didn’t understand the basement of the script; I didn’t understand that what happened with them is that they recognized each other because of how similar they were.” I think that’s very true.

AVC: Catherine has relationships with people who have killed, and seems to collect details about these people for her stories, to combine and synthesize them with her own impulses. In writing Catherine then, did you put a lot of yourself into her, in the sense that she is always eyeing and sizing up people?

JE: I think that’s very true and very right, and I have never been asked that question. But yes, I think that if you’re a writer and you’re committed to it, we use people—we use the details of our experiences with people, and in that sense what we’re doing is sort of cold. Sometimes we learn things about [people] almost with the notion of wanting to learn things because I might quote-unquote use it someday. In terms of my own [sense of] observation, it’s especially so in my case because English really is my second language. I came here when I was 6 years old; I spoke English with a thick accent until I was 18.

But simply in terms of developing the ear and listening, for a very long time and even sometimes to this day, when someone is talking to me sometimes I almost see the words across a screen in my head. That’s how closely I’m listening — I almost punctuate it as they speak. One of the reasons I think I went into journalism is because I was so intensely shy as a boy. Journalism forces you to talk to people; that’s what you do. There’s two things actually—journalism forces you to overcome that, and part of the journalistic ethic back in that day, or lack of ethic rather, was that journalists were all these hard-drinking, writerly people. When I grew up and decided I wanted to be a writer, my heroes were Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, all of them interestingly juicers, right? So the booze helped me to step out of myself. I started drinking when I was 14 years old. I’ve had bumps with it and thankfully I’m finally at the age of 78 completely straight.

AVC: What did you make of the film’s casting?

JE: I was a big fan of Michael [Douglas]. I’d known him slightly before, admired his work, and in many ways this was really Michael’s film. Sharon wound up stealing it in some ways, but he was the rock, he was in every scene, and it was told from that point-of-view. I was thrilled with Michael, and I didn’t really know Sharon’s work much outside of Total Recall. I knew she loved the script and had worked for some time to try to get the part, and that impressed me, if she loved the material that much. When I met her, I thought she was perfect, because I saw a kind of Midwestern cuddly quality combined with evil that was in the shadows, in parentheses, and it was in her eyes at times.

Paul’s take was that Sharon is evil and that’s why she was so good in the movie, and I disagree with that. I think she was terrific in the part. She knew that she would be really good, which is why she fought so hard. I think one of the things that happened to her was that the quality of her performance was totally blown out by that one famous scene. At that point it became a sexual, erotic thriller, and she was much better than that. Just flashing a certain part of her anatomy wouldn’t have held that movie together all these years, and it wouldn’t still be trending everywhere, because at this point, with the porn explosion, people have seen that part of the anatomy an awful lot. It’s not headline news anymore.

AVC: You touched on the fact that Paul Verhoeven came back to your original script eventually, but there was a period when Gary Goldman came on for a series of rewrites.

JE: Gary did very extensive rewrites from what I understand, two or three drafts, and one day, almost like Paul on the way to Damascus, Paul Verhoeven discovered that he didn’t get it, and drove it right back to the original. Now considering how publicly that happened, and how publicly Paul said what happened, with great guts and transparency, I’ll always respect him for that.

AVC: Writers get rewritten all the time, but was there any more or less emotion during that period when you walked away from Basic Instinct?

JE: Irwin Winkler and I left together. We’d done Betrayed and Music Box together and I thought he was just a superb producer. Variety had a headline saying, “Dawn Of A New Era In Hollywood” with the sale, right? And then a month later, or not even that long, a couple weeks later, they had a banner headline that said, “Eszterhas and Winkler Abandon Project.” I looked like a complete asshole. I’d been paid $4 million, and I gave Irwin one [million], I’d gotten all these headlines, and then we walk away. I felt like an idiot, but I felt there was no choice because the changes they were suggesting would have ruined the material. Michael was adamant that Sharon one-ups him at every turn, and he was just fervent about the notion that there was no redemption in the piece, and that she wins, that evil wins. Well, to remove that ambiguity and turn it into an ordinary TV thriller-kind of ending, because Michael wanted to shoot her at the end and end the movie that way, would have destroyed the film.

And I’ve publicly said often that if you believe in what you write you have to believe in what you write, and it seemed to me that if I really believed in this, never mind the publicity, I had to do this. And Irwin, God bless him, agreed completely. So we had a meeting with Michael and Verhoeven, and it was horrible. They stormed out of Irwin’s house. It was so bad that Irwin, who was a mild-mannered man, and a terrific man with great values, wound up yelling at Verhoeven, “You fucking Nazi, blah blah blah!” Well, Paul lost people during the Holocaust, so it was outrageous. But we were out of our heads. So I was very upset. And when Paul came back in, and did it so publicly, I thought, “Well, this truly is a rare man, to have done this.”

AVC: Back to “that scene” you mentioned, which of course as originally scripted wasn’t that direct or explicit.

JE: In almost every scene that was dicey, I had a line I would use: “It was dark, and you can’t see clearly.” But Paul comes onto the movie and one of the first Verhoeven movies I saw was a Dutch movie where there’s a penis that is severed and levitates over the credits, right? And in that particular scene that we’re talking about, the previous scene to it, down on Stinson Beach, Michael goes to see [Catherine], he sees that she’s not wearing any underwear, she’s changing and he sort of looks, and we get a fast glimpse that she’s wearing no underwear. Paul moved that, and I think it was genius, into that interrogation room [scene]. And so it took on a whole different mythological feeling, because she messed with those cops in there, and she beat them at their game. To move that nakedness into that room in that way was I thought was wonderful.

AVC: Both Paul and Sharon have described the filming of that scene, and the notion of consent or full disclosure, differently through the years. What does that say, still, about this country’s relationship with sex, female sexuality, and maybe different standards that it holds women to versus men?

JE: That’s a really good question. I’ve spoken to both of them about that scene, because I wasn’t on the set when it was shot. And it’s the only question you’ve asked me that I’m going to say no comment to, because of my friendship with both people.

AVC: Were you on set at all during shooting, as the film faced disruptive protests?

JE: Well, we were back and forth. Paul went off with Gary Goldman, and then we reunited. I was in on some meetings and discussions and then the gay community in San Francisco decided to launch a protest. Paul absolutely did not want to speak to them. I said, “Fine, I’ll speak to them,” as I knew many of the people involved; I’d lived in that area for a long time. Harry Britt was a pioneering gay supervisor in San Francisco, and I was big fan of his.

So at that famous meeting with the gay community, Paul didn’t want to attend, and he screamed at me and said, “You’re forcing me into this.” I walked in a little late, and Paul and Andy Fogelson and two or three other PR-type people were on one side, and Harry Britt and about 10 or 15 people were on the other side. I just walked in, looked at the two sides and sat down next to Harry, because he was my friend. And Paul of course viewed that as betrayal. [Laughs.] But Paul was weird with that stuff, because I heard later on that he actually put sandbags around his house in the Palisades because he was afraid that gay militants—Queer Nation I guess, because they had these T-shirts—were going to hurt his house, or hurt him or something like that. Things got very screwy there. So anyway, at that point I was asked not to be on the set, because we had such disagreements. I had criticized Alan Marshall, the line producer, who was making citizen’s arrests of protestors and walking them toward police wagons. I thought that was insanity.

AVC: The Nick and Catherine relationship sucks up a lot of oxygen when it comes to discussion of the film, but Nick and Beth’s relationship is also fascinating. The scene of rough sex between the pair—in the writing of it, did it feel provocative or envelope-pushing at the time?

JE: No. I never viewed it as date rape. And when the objections came up to it at that meeting that we had in San Francisco I was astounded that it was viewed as date rape. So was Paul. And I thought the way he shot it was ambiguous—it didn’t seem to me to be clearly date rape.

AVC: Were you comfortable, then, with how what you wrote for that scene was filmed?

JE: Yeah, I didn’t object to that scene at all, and I thought a lot about it after it was raised. [Pause.] I felt the way it was shot he pushed it and it was rough, but I didn’t quite think it quite amounted to date rape, especially in terms of their previous relationship.

AVC: Do you think that a film today could have that scene without the subsequent scene or scenes which unpack it, and perhaps soothe or address an audience’s anxiety or conflicted feelings over it?

JE: No, I don’t. In this time of woke-ism and cancelation, I don’t think that scene would be shot that way. Now, having said that, I just saw Paul’s latest movie, Benedetta, and he is such a provocateur to this day, and at his age, that anything is possible, so I’m certainly not speaking for him. But in my estimation in today’s climate it would be very, very difficult for that kind of rawness of that scene in the script. Woke-ism frightens me. #MeToo doesn’t, I think #MeToo is terrific and necessary—and certainly in terms of the business, very necessary. But woke-ism and cancellation is different turf in my mind.

AVC: How do you define those latter two respective terms, and what unnerves or frightens you about them so much?

JE: Well, let me tell you what I like about #MeToo to begin with, in terms of the business. I saw so many cases of women being used on occasion, and there was something very necessary, in my mind and my opinion, in terms of trying to change all that. There has been a change, from what I can tell. And I think it’s healthy for the business.

But when it goes totally overboard and people are cancelled for instances that aren’t definitive in my mind, then I think there’s an injustice being made. There is a rush to media judgement in our society. Before people are cancelled, I think more time should be spent and the cases should be looked at more closely, before something as deadly as taking someone’s career away—I think often there should be more investigation before that happens.

AVC: For the eventual sequel, did they come to you at all?

JE: By my memory, like six or seven years after [the first film] they did. I’m pretty sure I’m right. But the executive on the movie, and it was either UA or MGM, was a woman who felt that she wanted a feminine input into the film as well. And my deal was such that I got a $1.5 million whether I wrote it or not, and I didn’t want to go into a situation with an executive with that attitude to begin with because I didn’t want to have to worry about the politics of it. So I took my [money], finally saw the movie about seven or eight years after it was out, and of course thought it was terrible. The world agreed with me, for a change.

AVC: What are the qualities that most made Basic Instinct not just a hit upon release but also give it an enduring popularity?

JE: I think it has something to do with what Paul realized later on when he said he didn’t understand the basement of it. My notion, and you put your finger on it as well, is that it’s about two people who recognize a kind of evil in one another. I think that the film dealt with that in a way that most films don’t. It made it unique in some ways. The other is the ending, in that of course people endlessly come up to me and ask did she do it or not do it, and of course I have the standard cliché answer to that: “You better go watch it again.” And a lot of people have, I guess.