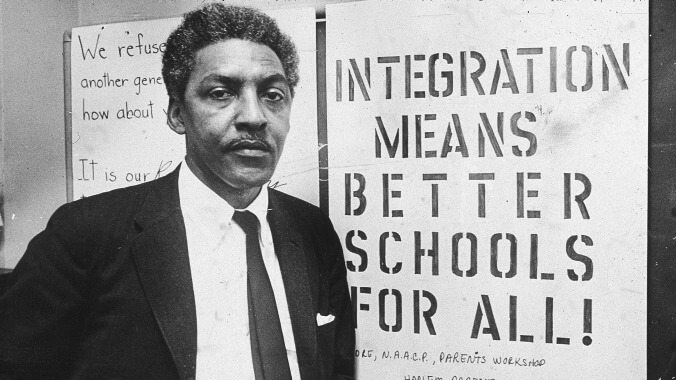

Bayard Rustin was a key figure in the civil rights and gay rights movements

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,101,066-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: Bayard Rustin

What it’s about: A leading figure in two civil rights movements whose name has been largely forgotten by history. Black activist Bayard Rustin marched on Washington in 1941 to protest the then-segregated Army. He helped organize Freedom Rides, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the 1963 March on Washington, but had to work largely behind the scenes, as he was openly gay. By the ’80s, Rustin had become a voice in the gay rights movement, amidst a lifetime spent campaigning for social justice.

Biggest controversy: Rustin covered the whole political spectrum over his lifetime. He began on the very far left, joining the Young Communist League in his ’20s (the pre-war Soviet Union supported the American civil rights movement, as inequality toward African Americans made the USSR’s supposed “worker’s paradise” look like more of a reality than it was).

When communists shifted their focus away from criticizing American racism and trying to entice America to join the Great Patriotic War, Rustin moved on to the Socialist Party. In 1964, Rustin was at the Democratic National Convention, trying to persuade the party to abandon pro-segregation Dixiecrats and embrace the cause of civil rights. By the ’70s, the Socialist Party had rebranded itself as “Social Democrats, USA,” and Rustin was the party’s co-chairman, criticizing both Nixon’s “reactionary policies,” and the “irresponsibility and elitism of ‘New Politics’ liberals.”

For reasons this Wiki page doesn’t explain, Rustin and other social democrats who were by this time staunchly anti-communist, made common cause with anti-communist conservatives, founding the neo-con movement, which reached its pinnacle with the George W. Bush administration and invasion of Iraq. Again, how Rustin’s politics led to resemble Donald Rumsfeld’s over the course of a few decades isn’t clear. But Rustin became friends and ideological allies with right-wing pundit Norman Podhoretz (who, although now retired, is a vocal Trump supporter), and was praised by Ronald Reagan after his death.

Strangest fact: Rustin also had a singing career. He went to college on a music scholarship as a tenor (first Wilberforce University, where he was expelled for organizing a strike, then Cheyney State Teachers’ College). In 1939, he sang in the chorus of a musical starring Paul Robeson and blues singer Josh White. White invited Rustin to join his band, and he performed regularly in Greenwich Village and put out several albums on Fellowship Records in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s (although only Bayard Rustin Sings A Program Of Spirituals is mentioned here)

Thing we were happiest to learn: Rustin was born into a tradition of activism. Born in 1912, he was raised by his grandparents. His grandmother, Julia Rustin, was an NAACP member who was friends with W.E.B. DuBois and James Weldon Johnson, and they (along with Julia) were profound influences, leading Rustin to begin campaigning against Jim Crow laws at a young age. His grandmother’s Quaker faith (Quakers are pacifists with a long history of activism), and a study of socialism and Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance also helped steer Rustin toward a life devoted to social justice.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: It was racism that prompted Rustin to come out of the closet. In 1942, more than a decade before the historic bus boycott started by Rosa Parks, Rustin was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a public bus. Rustin was heading to the back when a white child reached out to play with his necktie. The child’s mother instructed her not to touch him, using a racial slur. Rustin reasoned that if he acquiesced, he’d be teaching that child, “who was so innocent of race relations it was going to play with me,” would assume the mother’s slur and Rustin meekly going to the back of the bus were both appropriate. Instead, Rustin felt he owed it “not only to my own dignity, I owe it to that child” not to bow down to Jim Crow and segregation. Rustin realized soon after he also needed to live as an openly gay man, for similar reasons: “If I didn’t, I was part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was part of the effort to destroy me.”

David Platt, who dated Rustin in the ’40s, later said, “I never had any sense at all that Bayard felt any shame or guilt about his homosexuality. That was rare in those days. Rare.”

Also noteworthy: Later in life, Rustin adopted an adult man. In the early ’80s, Rustin was dating the much-younger Walter Naegle, who helped push Rustin to be a gay rights advocate. Because same-sex marriage was unthinkable at the time, Rustin legally adopted Naegle—as unsavory as that sounds to modern ears, it wasn’t an uncommon strategy for gay couples with a significant age gap, as it was the only way to get legal recognition as a family.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: After Rustin’s about-face on communism, he took up the cause of the Soviet Jewry Movement. The movement began with the Cleveland Council on Soviet Anti-Semitism, founded in 1963, which attempted to pressure the USSR (or push American politicians to pressure the USSR) to allow Jewish Soviets to practice their religion, preserve their culture, and emigrate to Israel if they so chose. Rustin saw the discrimination Jews faced in the USSR as being similar to the discrimination African Americans faced here, and was able to work with Senators Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Henry Jackson to pass trade sanctions over the USSR’s treatment of its Jewish population.

Further Down the Wormhole: We continue to celebrate Pride Month with another look at another key figure from LGBT history who was openly gay long before Stonewall—William Haines, a movie star from the 1920s who gave up his movie career rather than live in the closet. Stay safe out there, and we’ll take a look at Haines’ life and career next week.