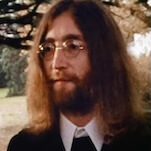

It feels like a cheat to reveal Beatlebone’s unfolding secret, or even the main character’s identity, and deprive readers of the surprises awaiting them within the pages of Kevin Barry’s second novel. There is the book’s cover—blowing its own cover, so to speak—featuring a silhouette of our hero, done up in the familiar George Dunning-style animation straight from Yellow Submarine, sitting atop the book’s title in mop-top, pensively puffing a cigarette.

In other words, the “John” whose burdensome thoughts we plunge into from page one is none other than John Lennon—the Beatle, the songwriter, the peacenik, the lover of Yoko—one of the most well-known figures in popular culture. This fact becomes the novel’s first, great obstacle. Of all the miraculous moments that abound in Beatlebone, the one easiest to miss is just how this John has been hollowed out from the inside, his Beatles-ness shed like an animal skin, and filled back up as a Barry-created Lennon that is strange but familiar too. There are the wisecracks, the quickness, the sharp tongue, and the wizard-like awareness of things seen and unseen. There is enough of the Lennon we think we know mixed in with this invention of Barry’s, whose prose has the wattage of a lightning bolt, to awaken another Frankenstein monster. But this particular creature is a musician from Liverpool gone macrobiotic and monkish, with a heroin habit not-so-firmly in the rear-view. In this feat alone, Beatlebone is no small miracle. We come to know a new Lennon, one that is neither a caricature nor a sketch, but a character in whom we can believe.

With so much cultural baggage to unpack in order to come at him anew, Lennon is not an easy man to tackle in a work of fiction. In particular, Barry’s novel plumbs the psychological depths of the singer and songwriter at his most desolate ebb, creative and romantic, in 1978, two short years before his assassination. As Barry imagines him, Lennon is at his wit’s end, in search of a solitude that is no longer afforded him even a decade removed from his band’s dissolution.

When we meet him, Lennon has entrusted himself to the care of his driver, Cornelius O’Grady, sitting in the back of a black Mercedes, in search of his island, Dorinish, off the western coast of Ireland in Clew Bay. If a novel needs a compass, a direction to which all of the prose points, pulling the narrative along with the anticipation of arrival, this is the general architecture of Beatlebone. Will this Beatle elude the encroaching “pressmen,” reach his land, and arrive at the solitude he seeks?

The actual destination is of secondary concern to Barry. The agony of Lennon, in this novelist’s version of him, resides in the desperation that accompanies the peeling away of identity, especially the one that has been thrust upon him by an adoring public. But this too gets only cursory coverage. There is the ever-present sense of cameras at his heels, and the tabloids are eager to understand the meaning of the chase they’ve been compelled to embark upon for a scoop they can’t predict or comprehend. Yet Beatlebone is a book about the dispiriting revelation at middle age of all the people you can’t become now that you’ve already been somebody else. This is as true for a postman as it is for a pop star.

So, John Lennon is on the run again, but this is a far cry from the smiling funhouse fame-fleeing lad from A Hard Day’s Night. Beatlebone is a sad, sea-haunted, beautiful book made even more so by prose so compressed and diamond-cut it rivals the sharpness of the crags that hang above Lennon as he braces his pale, underfed frame against the wind, fighting off waves to get to an impossible sanctuary in a world that has left him none.

“I mean it’s 1978!” Lennon exclaims more than once. It’s less a reminder of calendar time than a sad soul’s bellow of disbelief. Before he gets to where he’s going, Lennon sees about him the scraps that remain of a waning idealist counterculture, crossing paths with tired members of the Black Atlantis whose “rant” therapy mirrors Lennon’s own stint in California spent primal screaming with Dr. Arthur Janov. There are the easy-to-spot lyrical references (“He’s so tired. He hasn’t slept a wink.”), but others feel more slippery, with a sense that lyrics and historical references are folded into the prose so neatly even a Beatlemaniac might miss them. Nearly every sentence exhibits the care and craft of a poet. Barry doesn’t waste a word.

As Lennon boasts in one of his more puffed up and confident moments along his way to Dorinish, “I’m gonna be the first in human history that manages to outrun his own fucking shadow.” None of us can, of course, especially not the likes of John Lennon. But Barry has, in a way, managed to leave the Lennon shadow behind for the length of Beatlebone, presenting us with a protagonist that is entirely his own even if his name rings a very loud bell. It’s also a strange book whose compact, abundant wonders never feel like tricks. It’s up to you to decide if the talking seal is real.