In America, sometimes all it takes to make a million damn dollars is faith in one simple idea. In the mid-1960s, Robert Craig Knievel was already wowing crowds across the Northwest with the motorcycle stunt shows that he promoted, conceived, and starred in; but to grow his business, he started looking for opportunities to get into the newspaper and onto television, convinced that people around the world would line up to watch him perform if they just knew who he was. Knievel was absolutely right. By the end of the decade, after he’d been on TV a few times, viewers clamored for more of this man who’d nicknamed himself “Evel” (changing the spelling to avoid too much of a connection with the forces of darkness). Then in the 1970s he became a legitimate superstar, scoring phenomenal ratings for his increasingly elaborate jumps, and getting ridiculously rich by licensing his image to toys, comics, and dozens of other products.

As Daniel Junge’s documentary Being Evel explains, Knievel was doomed to fall hard. For one thing, he was a cantankerous cuss who regarded his heaping stacks of cash as a license to snarl at anyone who crossed him, intentionally or not—which eventually cost him a lot of goodwill with the same press he used to court. But the main reason why Knievel was bound to crash is that he nearly always crashed. He was great at dreaming up stunts that millions of people would want to see, but not so great at figuring out to execute them safely and successfully. That ended up being a major part of why he drew such a crowd. Modern daredevils use math and practice to assure that they’ll nail their tricks. Knievel just let it rip, offering the very real possibility that spectators might get to watch him die.

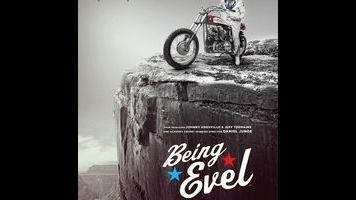

Being Evel could use a little more of its subject’s derring-do. Junge takes a flat talking-heads-and-archival-footage approach to this material, when the careening circus wagon that was Evel Knievel in the 1970s demands something freer and more kaleidoscopic. And while it’s admirable that producer (and Knievel disciple) Johnny Knoxville wants to acknowledge fully what a shit his boyhood hero could be, on the whole, Being Evel’s focus on the motorcyclist’s miserable personal life comes at the expense of more scenes of the man in action.

None of that though takes away from how jaw-dropping Being Evel can be—and how revealing, even to those who lived through the era when Knievel went from being a ubiquitous TV star to a tabloid joke. A couple of sequences in particular stand out: One’s a delirious montage of the superstar’s Scrooge McDuck-like excess, which saw him stockpiling boats, planes, and outrageous outfits. (“I risked my life for it, I’m spending every damn dime of it,” he explained.) The other’s a lengthy breakdown of Knievel’s attempt to cross Snake River Canyon in a steam-powered rocket, in a televised spectacle that attracted rowdy hordes of outlaw bikers and hundreds of increasingly irritated journalists.

Junge’s smartest move is to open Being Evel with the reminiscences of some sports reporters who recall when Knievel first started hyping himself up to them. The movie’s most significant subplot has to do with the role the media played in raising Knievel’s profile—and capitalizing on his popularity—before taking an almost cruel delight in painting him as a con artist and a thug. Being Evel’s story is too plain in the telling, but it’s still incredible, and relevant in the way it shows how a person can achieve wealth and fame if he’s willing to leap way high—and to endure the inevitable wipeout.